An American History Project of

The Lehrman Institute.

Please acknowledge

The Lehrman Institute

when using this research.

About The Gilder Lehrman Institute

Founded in 1994 by Richard Gilder and Lewis E. Lehrman, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization devoted to the improvement of history education. The Institute has developed an array of programs for schools, teachers, and students that now operate in all fifty states, including a website that features more than 60,000 unique historical documents in the Gilder Lehrman Collection.

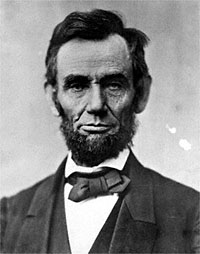

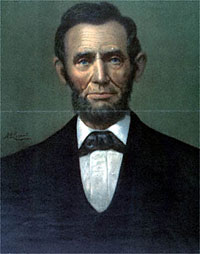

Mr. Lincoln

Americans of humbler birth but with more domestic political experience simply wanted jobs. Mr. Lincoln had enough disappointments with patronage to know its importance to a good political organization.

View Mr.Lincoln >>

The White House

Mr. Lincoln’s popularity with “the boys” was not tied to his indulgence in their vices. Indeed, he eschewed gambling, smoking and drinking. Mr. Lincoln managed to be one of the boys without being exactly like the boys.

View The White House>>

Nearby Washington

The war was never far from President Lincoln’s mind. When he left the White House, it was often to deal with a problem connected to the war.

View Nearby Washington>>

Residents & Visitors

In the four years between March 1861 and 1865, many politicians, generals, journalists, job seekers and relatives of Mrs. Lincoln passed through the doors of the White House.

View Residents & Visitors>>

Lincoln at Washington

Artist Francis B. Carpenter said that Abraham Lincoln referred to his office in the White House as the “shop.”

View Lincoln at Washington>>

Meeting Mr. Lincoln

“Beneath a smooth surface of candor and apparent declaration of all his thoughts and feelings he exercised the most exalted tact and wisest discrimination.”

View Meeting Mr. Lincoln >>