Poet Walt Whitman often observed Mr. Lincoln on the streets of Washington. He thought that the uniqueness of the President’s visage was never adequately captured with its “wonderful reserve, restraint of expression, fine nobility staring at you out of all that ruggedness…”1

Although President Abraham Lincoln’s face has been recorded for posterity as mournful, sad and serious, his contemporaries remembered its marvelous mobility. While the Civil War was a time of personal and patriotic heartbreak, the President found solace in humor, stories, the theater, and carriage rides around Washington. His critics were numerous and the pressures enormous. The President soldiered on. His assistant secretary, John Hay, observed in a letter dated August 7, 1863:

The Tycoon is in fine whack. I have rarely seen him more serene & busy. He is managing this war, the draft, foreign relations, and planning a reconstruction of the Union, all at once. I never knew with what tyrannous authority he rules the Cabinet, till now. The most important things he decides & there is no cavil. I am growing more and more firmly convinced that the good of the country absolutely demands that he should be kept where he is till this thing is over. There is no man in the country, so wise so gentle and so firm. I believe the hand of God placed him where he is.

They are working against him like beavers though; [Senator John Hale] & that crowd, but don’t seem to make anything by it. I believe the people know what they want and unless politics have gained in power & lost in principle they will have it.2

Edward Duffield Neil joined the small presidential staff in 1864. He noted that Mr. Lincoln’s “capacity for work was wonderful. While other men were taking recreation through the sultry months of summer, he remained in his office attending to the wants of the nation. He was never an idler or a lounger. Each hour he was busy.”3 Although observers frequently emphasized his contemplative nature, historian Bruce Catton observed, “Abraham Lincoln was not all brooding melancholy and patient understanding. There was a hard core in him, and plenty of toughness. He could recognize a revolutionary situation when he saw one, and he could act fast and ruthlessly to meet it.”4

Carl Schurz, a diplomat-turned-general who often visited the White House, wrote: “Those who visited the White House – and the White House appeared to be open to whosoever wished to enter – saw there a man of unconventional manners, who, without the slightest effort to put on dignity, treated all men alike, much like old neighbors; whose speech had not seldom a rustic flavor about it; who always seemed to have time for a homely talk and never to be in a hurry to press business, and who occasionally spoke about important affairs of State with the same nonchalance – I might almost say, irreverence – with which he might have discussed an every-day law case in his office at Springfield, Illinois.”5

Because of his German birth and political connections, Schurz was sometimes approached by foreigners seeking positions in the army. A German of noble birth prevailed upon Schurz to get an appointment with President Lincoln. “The count spoke English moderately well, and in his ingenuous way he at once explained to Mr. Lincoln how high the nobility of his family was, and that they had been counts so-and-so many centuries. ‘Well,’ said Mr. Lincoln, interrupting him, ‘that need not trouble you. That will not be in your way, if you behave yourself as a soldier.’ The poor count looked puzzled, and when the audience was over, he asked me what in the world the President could have meant by so strange a remark.”6

Americans of humbler birth but with more domestic political experience simply wanted jobs. Mr. Lincoln had enough disappointments with patronage to know its importance to a good political organization. So, from the outset of his Presidency, Mr. Lincoln was often diverted from important affairs of state to mundane affairs of political appointments that many observers thought beneath him. Mr. Lincoln knew, however, how critical they could be in maintaining a base of political and public support. “From the beginning of his tenure in the White House Lincoln was keenly aware of the fact that there were many other Republicans who greatly coveted the Presidency,” wrote historian John Hope Franklin. Some were brought “into the Cabinet not only to profit from their talent and experience but also to keep a weather eye on their political activities. Other powerful Republican Congressmen such as [Senator Charles Sumner and Congressman Thaddeus Stevens] he sought to cultivate in a number of ways and with varying degrees of success. Still others, the nameless hundreds of the party faithful, Lincoln sought to satisfy and retain the support of through the use of patronage.”7

Mr. Lincoln, therefore, according to historian Allen C. Guelzo, made sure the “last word in patronage” was his. “He intervened directly in numerous patronage appointments, overriding [Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair], and other cabinet officers to demand the hiring of certain party faithful or to provide reliable incomes for party workers. In August, 1861, when one of Chase’s lieutenants in charge of the Philadelphia mint hesitated to hire Elias Wampole, a loyal Lincoln campaigner in Illinois, Lincoln irritably insisted that a job be found for Wampole, even if it meant make-work. ‘You must make a job of it, and provide a place…You can do it for me, and you must.'”8 No job was too small to draw Mr. Lincoln’s attention because he recognized that all jobs were important to the petitioners. Charles Francis Adams expected a modicum of ceremony to accompany his appointment as U.S. minister to England, a critical job given the desire for diplomatic recognition by the Confederate government. When Adams thanked Mr. Lincoln for the appointment, he was appalled when the President attributed the choice completely to Secretary of State William Seward and then turned their attention immediately to filling the job of postmaster in Chicago.

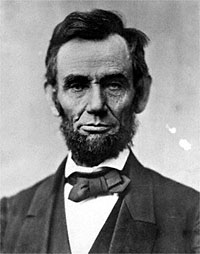

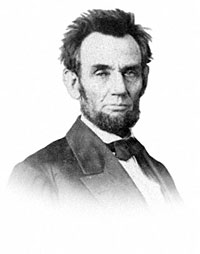

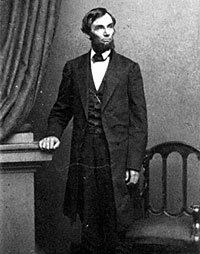

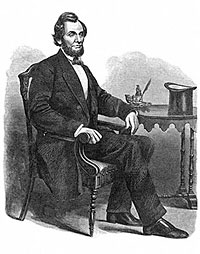

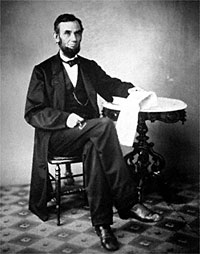

The Physical President

The President who preserved the Union, freed the slaves and kept European powers out of American affairs did not always impress at first glance. British journalist William Howard Russell described his first meeting with the President at the White House: “Soon afterward there entered, with a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions, which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet. He was dressed in an ill-fitting, wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertake’s uniform at a funeral; round his neck a rope of black silk was knotted in a large bulb, with flying ends projecting beyond the collar of his coat; his turned-down shirt-collar projecting beyond the collar of his coat; his turned-down shirt-collar disclosed a sinewy muscular yellow neck, and above that, nestling in a great black mass of hair, bristling and compact like a riff of mourning pins, rose the strange quaint face and head, covered with its thatch of wild republican hair, of President Lincoln. The impression produced by the size of his extremities, and by his flapping and wide projecting ears, may be removed by the appearance of kindliness, sagacity, and the awkward bonhommie of his face; the mouth is absolutely prodigious; the lips straggling and extending almost from one line of black bear to the other, are only kept in order by two deep furrows from the nostril to the chin; the nose itself – a prominent organ – stands out from the face with an inquiring, anxious air, as though it were sniffing for some good thing in the wind; the eyes dark, full, and deeply set, are penetrating, but full of an expression which almost amounts to tenderness; and above them project the shaggy brow, running into the small hard frontal space, the development of which can scarcely be estimated accurately, owing to the irregular flocks of thick hair carelessly brushed across it. One would say that, although the mouth was made to enjoy a joke, it could also utter the severest sentence which the head could dictate, but that Mr. Lincoln would be ever more willing to temper justice with mercy, and to enjoy what he considers the amenities of life, than to take a harsh view of men’s nature and of the world, and to estimate things in an ascetic or puritan spirit.”9

The White House years and the accompanying Civil War were very tough on President Lincoln. “Lincoln’s position, previous to [Fort Sumter’s surrender], was perilous. No clear-cut mandate could be drawn from the election that sent him to the White House,” wrote Lincoln scholars Paul Angle and Earl Schenck Miers. “Winfield Scott, his commanding general, was now so infirm that he could no longer mount a horse. Within the cabinet were three personalities – William H. Seward from New York, Secretary of State; Salmon P. Chase from Ohio, Secretary of the Treasury; and Simon Cameron from Pennsylvania, Secretary of War – who had coveted the presidential nomination at Chicago and who held no illusions concerning Lincoln’s limited experience in administration or military matters. Yet one day Seward would describe Lincoln as ‘the best man of us all’ and history would concur in that opinion….Steadfastness of will, fairness of judgment, humility of self, growth of mind and bigness of heart were the invincible attributes that Lincoln brought to Washington in those dark, bitter years when democracy as a workable form of government stood on trial before the world.”10

Physically, Mr. Lincoln aged quickly during the Civil War. In addition to the obvious problem of secession, the problems he faced on taking office would have sapped the vigor of any man, noted biographer and contemporary Isaac Arnold: “The treasury was empty; the national credit failing and broken; the nucleus of a regular army scattered and disarmed; the officers who had not deserted were strangers; the old democratic party which had rules foremost of the time for half a century, was largely in sympathy with the insurgents. Lincoln’s own party was made up of discordant elements; neither he nor his party had acquired prestige; nor had the party yet learned to have confidence in its leaders. He had to create an army, to find military skill and leadership by experience.”11

By mid-July 1862, the effects of the war had caught up to him, according to Senator Orville Browning, an old friend and political colleague. He found the President in the family library at the White House, avoiding visitors, and looking “weary, care-worn and troubled,” Browning wrote his diary: “I remarked that I felt concerned about him – regretted that troubles crowded so heavily upon him, and feared his health was suffering. He held me by the hand, pressed it, and said in a very tender and touching tone — ‘Browning I must die sometime’, I replied ‘your fortunes Mr President are bound up with those of the Country, and disaster to one would be disaster to the other, and I hope you will do all you can to preserve your health and life’. He looked very sad, and there was a cadence of deep sadness in his voice. We parted I believe both of us with tears in our eyes.”12

According to secretary John Hay, “Under this frightful ordeal his demeanor and disposition changed – so gradually that it would be impossible to say when the change began; but he was in mind, body, and nerves a very different man at the second inauguration from the one who had taken the oath in 1861. He continued always the same kindly, genial, and cordial spirit he had been at first; but the boisterous laughter became less frequent year by year; the eye grew veiled by constant mediation on momentous subjects; the air of reserve and detachment from his surroundings increased. He aged with great rapidity.”13

The stress President Lincoln was under was reflected in a story told by historian William C. Davis: “A caller in January 1865 heard the president talking to [a] woman seeking to get her husband out of the army because the family were impoverished. ‘I cannot grant your request. I can disband all the Union armies, but I cannot send a single soldier home,’ said Lincoln. ‘I sympathize in your disappointment, but consider that all of us in every part of the country are today suffering what we have never suffered.’ Of course, as commander-in-chief, Lincoln could send a soldier home, or certainly had the influence to make it happen; no sooner did he deny the woman than he apparently had a change of heart and gave her what she asked.”14

California journalist and Lincoln intimate Noah Brooks later wrote about the effects of the years of the Presidency: “No man but Mr. Lincoln ever knew how great was the load of care which he bore, nor the amount of mental labor which he daily accomplished. With the usual perplexities of the office – greatly increased by the unusual multiplication of places in his gift – he carried the burdens of the civil war, which he always called ‘This great trouble.’ Though the intellectual man had greatly grown meantime, few persons would recognize the hearty, blithesome, genial, and wiry Abraham Lincoln of earlier days in the sixteenth President of the United States, with his stooping figure, dull eyes, care-worn face, and languid frame. The old, clear laugh never came back; the even temper was sometimes disturbed; and his natural charity for all was often turned into an unwonted suspicion of the motives of men, whose selfishness cost him so much wear of mind. Once he said, ‘Sitting here, where all the avenues to public patronage seem to come together in a knot, it does seem to me that our people are fast approaching the point where it can be said that seven-eighths of them were trying to find how to live at the expense of the other eighth.'”15 But he refused to cut back on his contacts with the public. He told Massachusetts Sen. Henry Wilson that his visitors “don’t want much; they get but little, and I must see them.”16

Pressures of Office

“The suspicion is inevitable that sometimes Lincoln was taken advantage of, especially by those able to see him personally and plead their cases face to face,” wrote William C. Davis in Lincoln’s Men. He was particularly susceptible to the appeals of widows. Mr. Lincoln “made efforts to procure something to assuage the grief of those left behind after a soldier’s death. The widow of a soldier killed in late 1863 appealed to him. ‘I haint got no pay as was cummin toe him and none of his bounty munney.’ She asked Lincoln to help her find a job in Washington, adding, ‘I no yu du what is rite and yu will see to me a pore widder wumman.’ And so he did. To one widow he gave an appointment as postmaster; for another, whom he called ‘the best woman I ever knew,’ he strained a point to give her only surviving son a commission as a lieutenant in the 3rd United States Infantry after he had already served a year in the volunteers.”17

Mr. Lincoln derived pleasure from helping those Americans who had no other recourse. He could distinguish between those who were abusing his patience and those who had been abused by life. Joshua Speed was an old and valued friend from Springfield. He met with Mr. Lincoln in late February, 1865: “Congress was drawing to a close; it had been an important session; much attention had to be given to the important bills he was signing; a great war was upon him and the country; visitors were coming and going to the President with their varying complaints and grievances from morning till night with almost as much regularity as the ebb and flow of the tide; and he was worn down in health and spirits. On this occasion I was sent for, to come and see him. Instructions were given that when I came I should be admitted. When I entered his office it was quite full, and many more – among them not a few Senators and members of Congress – still waiting. As soon as I was fairly inside, the President remarked that he desired to see me as soon as he was through giving audiences, and that if I had nothing to do I could take the papers and amuse myself in that or any other way I saw fit till he was ready.”

When Speed entered Mr. Lincoln’s office, “I observed sitting near the fireplace, dressed in humble attire, two ladies modestly waiting their turn. One after another of the visitors came and went, each bent on his own particular errand, some satisfied and others evidently displeased at the result of their mission. The hour had arrived to close the door against all further callers. No one was left in the room now except the President, the two ladies and me. With a rather peevish and fretful air he turned to them and said, ‘Well, ladies what can I do for you?’ They both commenced to speak at once. From what they said he soon learned that one was the wife and the other the mother of two men imprisoned for resisting the draft in western Pennsylvania. ‘Stop,’ said he, ‘don’t say any more. Give me your petition.’ The old lady responded, ‘Mr. Lincoln, we’ve got no petition; we couldn’t write one and had no money to pay for writing one, and I thought best to come and see you.’ ‘Oh,’ said he, ‘I understand your cases.'”

President Lincoln summoned Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana to bring a list of western Pennsylvanians in jail for evading the draft. President Lincoln told Dana that “these fellows have suffered long enough.” The President had determined to set them all free and ordered Dana to draw an order to do so. “Turning to the women he said, ‘Now, ladies, you can go.’ The younger of the two ran forward and was in the act of kneeling in thankfulness. ‘Get up,’ he said; ‘don’t kneel to me, but thank God and go.’ The old lady now came forward with tears in her eyes to express her gratitude. ‘Good-bye, Mr. Lincoln,’ said she; ‘I shall probably never see you again till we meet in heaven.’ These were her exact words. She had the president’s hand in hers, and he was deeply moved. He instantly took her right hand in both of his and, following her to the door, said, ‘I am afraid with all my troubles I shall never get to the resting-place you speak of; but if I do I am sure I shall find you. That you wish me to get there is, I believe, the best wish you could make for me. Good-bye.”18

“Never did I see Lincoln so full of grief or of his own affairs that he was not ready to sympathize with all who needed him, especially if a child called for help,” wrote Sergeant Smith Stimmel. “I think he never passed by a child without a smile, and some way, in spite of sad eyes and heavy brows, the children always took to him. One morning, when the President came over from the War Department, some little school children were playing on the front steps of the White House. He stopped and had a word of pleasantry with them, took one or two of their books and glanced through them, and while he did so, the children crowded around him as if he had been their father.”19

It wasn’t just ordinary citizens who nagged the President, according to historian Michael Burlingame. “At times Mary Lincoln would, in effect, blackmail her husband by behaving like a spoiled child,” wrote Burlingame. She nagged him on many subjects, according to Burlingame, including politicians and generals: “Mary Lincoln did not mellow with age; she continued to berate her husband in the White House. On February 22, 1864, while attending a Patent Office fair to benefit the Christian Commission, Lincoln was caught off guard by the crowd’s insistence that he make a speech. According to his friend Richard J. Oglesby, who had prevailed upon him to attend the meeting only by promising that he would not have to speak, Lincoln reluctantly acceded to the crowd’s importunings and delivered a few remarks. Afterward, while the Lincolns and Oglesby awaited their carriage, Mary Lincoln allegedly said to her husband, ‘That was the worst speech I ever listened to in my life. How any man could get up and deliver such remarks to an audience is more than I can understand. I wanted the earth to sink and let me go through.’ The president did not reply; in fact, during the ride home, no further words were spoken by Oglesby or the Lincolns.”20

Mrs. Lincoln’s personal conduct was also a trial for the President. Consistently jealous of Mr. Lincoln’s courteous behavior toward women, she herself threw tantrums and engaged in flirtations that caused public scandal and private grief for her husband. She was also jealous of potential rivals to her husband – such as Secretary of State William Henry H. Seward and General Ulysses S. Grant. Burlingame wrote that on April 13, 1865, the day before her husband’s death, “she asked General Grant to escort her to view the illuminated capital buildings. At the urging of the president, he accepted, and as the two entered their coach, the huge crowd gathered at the White House lustily cried out ‘Grant’ nine times, ‘whereupon Mrs. [Lincoln] was disturbed, and directed the driver to let her out.’ But when the crowd then cheered for Lincoln, she gave orders to proceed. This ‘was repeated at different stages of the drive’ whenever the crowd learned the identity of the coach’s occupants. Evidently Mary found it unsettling that Grant should be cheered first. The following day the general, when invited by the president to attend Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater, declined lest he endure Mary Lincoln’s displeasure yet again.”21

The final months of the war were particularly difficult physically for President Lincoln, who had lost a beloved son and thirty pounds at the White House. After his friend Joshua Speed watched him deal with a parade of visitors and disconsolate petitions, the President admitted: “I am very unwell now; my feet and hands of late seem to be always cold, and I ought perhaps to be in bed; but things of the sort you have just seen don’t hurt me, for, to tell you the truth, that scene is the only thing today that has made me forget my condition or given me any pleasure.”22 There was considerable physical vigor left in the President when he was assassinated. “”There was no waste or excess of material about his frame; nevertheless he was very strong and muscular. I remember that the last time I went to see him at the White House – the afternoon before he was killed – I found him in a side room with coat off and sleeves rolled up, washing his hands,” reported Charles A. Dana, who was one of the country’s most distinguished journalists. “He had finished his work for the day, and was going away. I noticed then the thinness of his arms, and how well developed, strong and active his muscles seemed to be. In fact, there was nothing flabby or feeble about Mr. Lincoln physically. He was a very quick man in his movements when he chose to be, and he had immense physical endurance. Night after night he would work late and hard without being wilted by it. And he always seemed as ready for the next day’s work as though he had done nothing the day before.”23

Still, the President felt exhausted. Journalist Noah Brooks recalled the President telling him of his White House experience: “I sometimes fancy that every one of the numerous grist ground through here daily, from a Senator seeking a war with France down to a poor woman after a place in the Treasury Department, darted at me with thumb and finger, picked out their especial piece of my vitality, and carried it off. When I get through with such a day’s work there is only one word which can express my condition, and that is – flabbiness.”24 But after the Union victory in early April 1865 and his visit to Richmond, Virginia, he returned to Washington refreshed, in the opinion of Attorney General James Speed, who commented on his “shaved face, well brushed clothing and neatly combed hair and whiskers.”25

Managing Politics

John Hope Franklin concluded that President Lincoln “appreciated, as few Americans have, the political nature of the Presidency. He never forgot this hard fact, and he always acted in a manner that demonstrated his full appreciation of the fact.”26 Philip Shaw Paludan, author of The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, wrote how Mr. Lincoln’s personal qualities shaped his political success: “An inspirer of loyalty and a manipulator of the ambitions of others, a man who made few personal enemies and yet, through sharing his true feelings with few people, maintained his independence of action, a man who had learned to wait for the tide to sweep or for events to turn his way, Lincoln may have been exceptionally well prepared to lead a nation resting on the consent of the governed.”27

Shelby Foote, author of The Civil War, compared President Lincoln to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, writing that “unlike his opponent, he had no fixed policy to refer to: not even the negative one of a static defensive, which, whatever its faults, at least had the virtue of offering a position from which to judge almost any combination of events. This lack gave him the flexibility which lay at the core of his greatness, but [he] had to purchase it dearly in mid-night care and day-long fret. Without practical experience on which to base his decisions, he must improvise as he went along, like a doctor developing a cure in the midst of an epidemic. His advisers were competent men in the main, but they were fiercely divided in their counsels; so that, to all his other tasks, Lincoln had added the role of mediator, placing himself as a buffer between factions, to absorb what he could of the violence they directed at each other. What with generals who balked and politicians who champed at the bit, it was no wonder if he sometimes voiced the wish that he were out of it, back home in Illinois. Asked how he enjoyed his office, told of a tarred and feathered man out West,, who, as he was being ridden out of town on a rail, heard one among the crowd call to him, asking how he liked it, high up there on his uncomfortable perch. ‘If it wasn’t for the honor of the thing,’ the man replied, ‘I’d sooner walk.'”28

Historian Richard N. Current, author of The Lincoln Nobody Knows, stressed Mr. Lincoln’s skills as a “master politician: “He had a way with politicians. ‘You know I never was a contriver,’ [Alexander McClure] heard him say in his quaint, disarming manner to a group of Pennsylvanians he had summoned to the White House; ‘I don’t know much about how things are done in politics, but I think you gentlemen understand the situation in your State, and I want to learn what may be done to insure the success we all desire.’ He proceeded to interrogate each man minutely about the campaign then in progress, about the weak points of the party and the strong points of the opposition, about the tactics to be used in this locality or that. Generalities, mere enthusiasm, did not interest. He wanted facts. And he got them, along with the wholehearted cooperation of the gentlemen from Pennsylvania.”29

“Lincoln was a great war leader because he was able to reach the hearts and minds of enough people to win the war,” wrote historian William Hanchett. “Lincoln understood the crucial importance of public opinion in a democracy. ‘Public opinion in this country ,’ he said truly, ‘is everything.’ Any policy to be permanent must have public opinion at the bottom. He was able to shape or influence public opinion on the vital issues because he wrote and spoke with a clarity and precision and used language, rich in metaphors, the people understood.”

The Release of Humor

Often, that meant telling stories laced with humor. Mr. Lincoln said: “I have found in the course of long experience [that people] are more easily influenced and informed through the medium of a broad illustration than in any other way, and as to what the hypercritical few may think, I don’t care.”30

Humor was central to Mr. Lincoln’s style of leadership. He enjoyed humorous writing – such as that by Artemus Ward and Petroleum Nasby – and could recite it from memory. “The continual interweaving of good fun in his writings and speeches shows that humor was no mere technique, but a habit of his mind,” wrote biographer James G. Randall. He noted that humor served as a way to avoid a question or avert a problem, but also his “laughter was a kind of release. It was [William H. Seward’s] impression that he ‘had no notion of recreation as such; enjoyed none; went thro’ levees &c purely as a duty – found his only recreation in telling or hearing stories in the ordinary way of business – often stopped a cabinet council at a grave juncture, to jest a half hour with the members before going to work; joked with every body, on light & on grave occasions. This was what saved him.”31

Not everyone appreciated Mr. Lincoln’s humor. Cabinet members Edwin M. Stanton and Salmon P. Chase were frequently left unamused by his stories. When Chase came to the White House one day to complain about the impossible burden of war expenditures on the Treasury, President Lincoln suggested that the only solution might be to “give your paper mill another turn.” The playful suggestion that printing greenbacks would solve the problem “disgusted” Chase.32 In late 1862, Congressman James M. Ashley called on the President shortly after a military disaster. Mr. Lincoln commenced to tell a story. The Congressman rose “Mr. President, I did not come here this morning to hear stories. It is too serious a time.” Mr. Lincoln responded: “Ashley, sit down! I respect you as an earnest, sincere man. You can not be more anxious than I have been constantly since the beginning of the war; and I say to you now, that were it not for this occasional vent, I should die.”33

Many stories were attributed to Mr. Lincoln, whether or not he actually recited them. Some of them were said to be improper. Former Congressman Isaac Arnold was one of the earliest of Mr. Lincoln’s biographers and knew him well: “Mr. Lincoln has been charged with telling coarse and indecent anecdotes. The charge, so far as it indicates any taste for indecency, is untrue. His love for the humorous was so strong, that if a story had this quality, and was racy or pointed, he did not always refrain from narrating it because the incidents were coarse. But it was always clear to the listener that the story was told for its wit and not for its vulgarity. ‘To the pure all things are pure,’ and Lincoln was a man of purity of thought as well as of life.”34

Intellectual Capacity

The president had an extraordinary memory – which helped to deal with people and tell stories. He had little memory, however for past slights and insults. “A man has not the time to spend half his life in quarrels. If any man ceases to attack me, I never remember the past against him,” Mr. Lincoln is said to have remarked on the night of his reelection in 1864.35 Like many observers, writer Stefan Lorant noted that Mr. Lincoln “had a capacity to grow. ‘Horace Greeley told of him that ‘there was probably no year of his life when he was not a wiser, cooler and better man than he had been the year before.'”36

Mr. Lincoln liked to explore problems not necessarily connected with the problems of war. “Lincoln had a questing mind,” according to biographer Benjamin P. Thomas. “He sometimes went to the Observatory to study the moon and stars, and it gave him unusual satisfaction to talk with men of broad intellect. Louis Agassiz, the scientist, and Dr. Joseph Henry, curator of the Smithsonian Institution, both marveled at his intellectual grasp. It must have delighted a man of his meager educational opportunities when Princeton (then known as the College of New Jersey), Columbia, and Knox College, in Illinois, saw fit to honor him with degrees of Doctor of Laws, and when Lincoln College, in Illinois, was named for him, as the town where it was located had been. But while Lincoln relished and appreciated the cultural side of life, he was no less keenly interested when Herman the Magician came to the White House and performed his tricks in slow motion to show how they were done.”37

“Mr. Lincoln was not what is called an educated man. In the college that he attended a man gets up at daylight to hoe corn, and sits up at night by the side of a burning pine-knot to read the best book he can find. What education he had, he had picked up. He had read a great many books, and all the books that he had read he knew. He had a tenacious memory, just as he had the ability to see the essential thing. He never took an unimportant point and went off upon that; but he always laid hold of the real question, and attended to that, giving no more thought to other points than was indispensably necessary,” wrote Charles A. Dana, who was both an administration official and a distinguished newspaper editor. “Thus, while we say that Mr. Lincoln was an uneducated man in the college sense, he had a singularly perfect education in regard to everything that concerns the practical affairs of life. His judgment was excellent, and his information was always accurate. He knew what the thing was. He was a man of genius, and contrasted with men of education the man of genius will always carry the day.”38

Humor was only one of Mr. Lincoln’s diversions as President. Sergeant Smith Stimmel served on the President’s security detail and often escorted him to and from the White House to the Soldiers Home where he spent summer evenings. One occasion, the security detail was diverted into a cow pasture so that a dispute could be resolved between Mr. Lincoln and the lieutenant in charge of the Detail. The lieutenant subsequently told Stimmel: “As we were coming along, the conversation turned upon the peculiar structure of the cow, and the President remarked that the cow is a lop-sided animal, that is, one side is higher than the other. Is aw no, that I never noticed that one side of a cow is higher than the other. ‘Well, it is,’ said the President, and when he saw those cows feeding over on the commons, he said, ‘We will just go over to those cows yonder, and I will show you that I am right about that!'” Stimmel was first surprised that Mr. Lincoln could be diverted by such a silly controversy but later said he came to understand that “he greatly needed some diversion.”39

Shakespeare

Mr. Lincoln also enjoyed humorous and mournful poetry. Orville Browning was an old friend, a frequent visitor and a private critic of President Lincoln On April 25, 1863, Browning recorded his diary his evening visit to the White House: Mr. Lincoln “was alone and complaining of head ache. Our conversation turned upon poetry, and each of us quoted a few lines from Hood. He asked me if I remembered the Haunted House. I replied that I had never read it. He rang his bell – sent for Hood’s poems and read the whole of it to me, pausing occasionally to comment on passages which struck him as particularly felicitous. His reading was admirable and his criticisms evinced a high and just appreciation of the true spirit of poetry. He then sent for another volume of the same work, and read me the ‘lost heir’, and then the ‘Spoilt Child’ the humour of both of which he greatly enjoyed. I remained with about an hour & a half, and left high in high spirits, and a very genial mood; but as he said a crowd was buzzing about the about the door like bees, ready to pounce upon him as soon as I should take my departure, and bring him back to a realization of the annoyances and harrassments of his position.”40

Another diversion was drama, especially Shakespeare. Psycho-biographer Charles Strozier noted: “No writer appealed more to Lincoln than Shakespeare. Some of the plays – King Lear, Richard II, Henry VI, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Hamlet, and, his favorite, Macbeth – he knew virtually by heart. He was fond of talking with James H. Hackett, the actor, of the subtle meanings of different characters and passages. John Hay noted on December 13, 1863, that a conversation between Lincoln and Hackett ‘at first took a professional turn, the Tycoon showing a very intimate knowledge of those plays of Shakespeare where Falstaff figures.’ Hay also noted a few days later that Lincoln went to Ford’s theater with him, Nicolay, and Swett to see Hackett in Henry IV. Lincoln thoroughly enjoyed the performance, though he disputed Hackett’s interpretation of one line. It seems clear that Lincoln turned repeatedly to Shakespeare for the depth of his insight into human motivation, the cleverness of his wit, and, perhaps, most basically of all, for the aesthetic appeal of his language. Lincoln continually sought to chasten and perfect his style; in Shakespeare, and probably nowhere else, he found a master whose own creativity provided a model.”41

Walt Whitman found another way of comparing Mr. Lincoln and Shakespeare. “One of the best of the late commentators on Shakespeare,” wrote Whiteman, makes the height and aggregate of his quality to be that he thoroughly blended the ideal with the practical or realistic. If this be so, I should say that what Shakespeare did in poetic expression, Abraham Lincoln essentially did in his personal and official life. I should say the invisible foundations and vertebrae of his character, more than any man’s in his personal and official life, were mystical, abstract, moral and spiritual – while upon all of them was built, and out of all of them radiated, under the control of the average of circumstances, what the vulgar call horse sense, and a life bent by temporary but most urgent materialistic and political reasons.”42

“To some indeterminable extent and in some intuitive way, Lincoln seems to have assimilated the substance of the plays into his own experience and deepening sense of tragedy,” wrote historian Don Fehrenbacher. “That he should have done so is scarcely surprising. For in most of his favorite plays, power and politics are the central theme….The central figure in these plays is usually a king – that is, a head of state like Lincoln – whose court is a place of tension and intrigue, and who spends much of his time hearing requests for favors, conferring with advisers, planning military campaigns, and devising counterplots against treason.”43

Aide William O. Stoddard sometimes accompanied the President to the theater and observed his fascination with the problems of Shakespeare’s lead characters like Lady Macbeth and Othello. “His strong love of humor made Falstaff a great favorite with him, and he expressed a great desire to see [Shakespearean actor James Hackett] in that character,” wrote Stoddard. “I was with him the first night [of Hacket’s engagement], and expected to see him give himself up to the merriment of the hour, although I knew that his mind was very much preoccupied by other things. To my surprise, however, he appeared even gloomy, although intent upon the play, and it was only a few times during the whole performance that he went so far as to laugh at all, and then no heartily. He seemed for once to be studying the character and its rendering critically, as if to ascertain the correctness of his own conception as compared with that of the professional artist.”

Roy P. Basler, who compiled the monumental Collected Words of Abraham Lincoln, observed that Mr. Lincoln could easily identify with the tragic complexity of Shakespeare’s characters: “Like Henry VI Lincoln had attained the rule’s seat in a divided nation and almost daily was confronted with the special horrors and tragedies of a civil war in which families were divided in mutual slaughter. This was brought into in his immediate family by the death at Chickamauga of Confederate Brigadier General Ben Hardin Helm, Mary Todd Lincoln’s brother-in-law, for whose grief-stricken but still rebellious widow, [Emilie Todd Helm], Lincoln extended courtesies that almost breached military discipline as well as political prudence, in bringing her through the lines and into the White House in December 1863.”44

Mr. Lincoln enjoyed an audience for his own performances of Shakespeare – often picking on those with whom he was comfortable, such as secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay. Carl Sandburg noted that President Lincoln was particularly comfortable with the staff of the War Department’s telegraph office, run by Thomas Eckert and David Homer Bates: “The President was more at ease among the telegraph operators than amid the general run of politicians and office seekers. Bates noted that Lincoln carried in his pocket at one time a well-worn copy in small compass of Macbeth and the Merry Wives of Windsor, from which he read aloud. ‘On one occasion,’ said Bates. I was his only auditor and he recited several passages to me with as much interest apparently as if there had been a full house.'”45 Basler observed that after the Battle of the Wilderness, Mr. Lincoln found solace in reading out loud the soliloquy from Macbeth. He told editor-politician John W. Forney that “it comes to me tonight as a consolation”:

To-morrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day.

To the last syllable of recorded time.

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a weak shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more; it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.46

Mr. Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865 assigned him a preeminent place in the tragic tradition. Although he enjoyed Shakespeare’s comedies, he became immersed in Shakespeare’s tragedies. “Lincoln’s love for Shakespeare dated back to his youth but was intensified during the presidential years; for then his new circumstances lent new personal meaning to certain plays and passages. And although he enjoyed seeing Edwin Booth as Hamlet or Edwin Forrest as King Lear, what he liked best of all was to corner an acquaintance or one of his secretaries and read some of his favorite lines aloud. The artist Francis B. Carpenter, for example, once heard him recite the opening soliloquy from Richard III ‘with a degree of force and power that made it seem like a new creation,'” wrote historian Don E. Fehrenbacher. Artist Francis Carpenter “quotes him as saying on one occasion: ‘It matter not to me whether Shakespeare be well or ill acted; with him the thought suffices.’ To some indeterminable extent and in some intuitive way, Lincoln seems to have assimilated the substance of the plays into his own experience and deepening sense of tragedy.”47

Managing the War

Neither humor nor Shakespeare could erase the tragedy of the war and the impact of that war on Union soldiers and their families. On his afternoon carriage drives, he often stopped by Union camps and hospitals to visit. “The welfare of the men, their troubles, escapades, amusements, were treated by the President as a kind of family matter. He never forgot to ask after the sick, often secured a pass or a furlough for some one, and took genuine delight in the camp fun,” noted biographer Ida Tarbell. But the sadder and more tragic problems of the soldiers often ended up in Mr. Lincoln’s office – requests for furloughs, passes, promotions, clemencies and pardons. “The futility of trying to help all the soldiers who found their way to him must have come often to Lincoln’s mind. ‘Now, my man, go away, go away,’ General Fry overheard him say one day to a soldier who was pleading for the President’s interference in his behalf; ‘I can’t meddle in your case. I could as easily bail out the Potomac with a teaspoon as attend to all the details of the army.'”48

Generals could be even more cause for aggravation than common soldiers. George B. McClellan gave the President particular aggravation in 1861-62. “McClellan the strategist made little effort to hide his innate hostility toward authority, and in the matter of his plans of campaign, for example, he managed to alienate almost every supporter he had ever had in the Cabinet. With deliberate scorn, when he sailed for the Peninsula, he tossed off a jumbled, directionless plan for the defense of Washington that left Mr. Lincoln, his sole important supporter in the administration, ‘justly indignant,'” wrote McClellan biographer Stephen W. Sears.49

Generals could cause Mr. Lincoln trouble, but those like George McClellan who underestimated the President did so at their peril. “Any had a right, it was supposed to advise him of his duty; and he was so conscious of his shortcomings as a military President that the army officers and Cabinet would run the Government and conduct the war. That was the popular idea. Little did the press, or people, or politicians then know that the country lawyer who occupied the executive chair was the most self-reliant man who ever sat in it, and that when the crisis came his rivals in the Cabinet, and the people everywhere, would learn that he and he alone would be master of the situation,” wrote William Herndon, Mr. Lincoln’s lawyer partner and one of the first to compile biographical information on him.50

“With no knowledge of the theory of war, no experience in war, and no technical training, Lincoln, by the power of his mind, became a fine strategist. He was a better natural strategist than were most of the trained soldiers. He saw the big picture from the start,” wrote historian T. Harry Williams. “The policy of the government was to restore the Union by force; the strategy perforce had to be offense. Lincoln knew that numbers, material resources, and sea power were on his side, so he called for 400,000 troops and proclaimed a naval blockade of the Confederacy. These were bold and imaginative moves for a man dealing with military questions for the first time. He grasped immediately the advantage that numbers gave the North and urged his generals to keep up a constant pressure on the whole strategic line of the Confederacy until a weak spot was found – and a break-through could be made.”51

British military historian Colin Ballard wrote that Mr. Lincoln “had a fine grasp of the big situation. He realized that numbers, resources, and command of the sea were on his side; these factors must eventually wear down the resistance of the South, provided that no opportunity were given to a clever enemy to deal a knock-out blow before the resources of the North were fully developed. Though he had no personal knowledge of the Southern leaders, his keen insight soon recognized their daring brilliance.” He had to prepare for the possibility of a sudden invasion of the area near Washington, and “therefore his first object was to avoid such blows until he was ready with his counterstroke. It was not timidity or want of enterprise that kept so much of his force on the defensive, it was the wisdom of a strategist who could look ahead, it was the courage which faces censure and overrides the maxims of conventional warfare.”52

President Lincoln lacked the extensive military background of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, a West Point graduate and former secretary of war. Historian Steven Woodworth studied Davis’s relationships with Confederate generals and concluded that President Lincoln had three advantages over Davis, who was chronically sick and perpetually argumentative: “First, Lincoln was a fast learner, quickly grasping new concepts and new ways of doing things. He could not only grow into a job but also grow with the job as its demands changed or became greater. Second, Lincoln had a an ability to withstand tremendous pressure and fatigue and yet maintain his good judgment; and ability to get along with people; and an extraordinary ability to cut to the heart of whatever problem was under consideration. Finally, Lincoln had the self-confidence, the nerve, or whatever it was he needed to take decisive action.”53

Davis’s advantage over President Lincoln was in the selection in June 1862 of Robert E. Lee to head the Confederate army in Virginia. It took President Lincoln nearly another two years to come to a similarly fortuitous choice. “In Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln found a general who fulfilled all his expectations. Grant understood his position within the political-military hierarchy, exhibited enough savvy not to embroil himself in politics, restrained his ambition, and functioned effectively with the available resources. While President Lincoln wrestled with the war’s political aspects, he selected Grant as lieutenant general to invigorate the military components as he had done in the West. Grant did just that,” wrote historian James Glatthaar. “Together, the Lincoln-Grant team functioned exceedingly well. Lincoln adroitly guided Grant through political minefields, and the new commanding general assumed the mantle for army operations. As commander in chief, Lincoln kept a watchful eye on military affairs. After all, it was the president’s responsibility. Whenever Lincoln disagreed with a Grant decision, he merely questioned it, voicing his objections and laying out possible repercussions…With Grant, a man sensitive to the wishes of his superior, Lincoln had a most trustworthy and reliable subordinate.54

Grant’s approach was in stark contrast to that of McClellan, who enjoyed the pomp and show of military reviews but had little stomach for battle. After his appointment as Union Commander in March 1864 was greeted by a near mob scene at the White House, Grant returned briefly visited General George Meade and the Army of the Potomac. Before going back to Tennessee, Grant returned to the Washington where President Lincoln pressured him to attend a White House dinner that Mrs. Lincoln had arranged. Grant turned him down firmly, saying, “Really, Mr. President, I have had enough of this show business.”55 Having found a general he trusted, Mr. Lincoln made his trust clear, telling aide William O. Stoddard: “Grant is the first general I’ve had! He’s a general!”56

Managing the Cabinet

Cabinet secretaries needed to understand a similar lesson about the way President Lincoln directed the government. Salmon P. Chase sought to position himself to succeed President Lincoln in 1864. “From the beginning Mr. Lincoln had been aware of this quasi-candidacy, which continued all through the winter [of 1863-64]. Indeed, it was impossible to remain unconscious of it, although he discouraged all conversation on the subject, and refused to read letters relating to it. He had his own opinion of the taste and judgment displayed by Mr. Chase in his criticisms of the President and his colleagues in the cabinet, but he took no note of them,” remembered John Nicolay, Mr. Lincoln’s secretary and biographer. “I have determined,’ he said, ‘to shut my eyes, so far as possible, to everything of the sort. Mr. Chase makes a good secretary, and I shall keep him where is. If he becomes President, all right. I hope we may never have a worse man.”57

At times like this, Mr. Lincoln could not simply shut his eyes. He could shut out the world. John Nicolay wrote that Mr. Lincoln’s “prevailing mood in later years was one of meditation. Unless engaged in conversation, the external world was a thing of minor interest. Not that he was what is called absentminded. He did not forget the spectacles on his nose, and his eye and ear lost no sound or movement about him when he sat writing in his office or passed along the street. But while he noted external incidents, they remained second. His mind was ever busy in reflection. Sometimes he would sit for an hour, still as a petrified image, his soul absent in the wide realm of thought.”58

Mr. Lincoln was motivated by his strong sense of the history and formation of the United States. “Before taking the oath of office as president, Lincoln made a point of raising a flag at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where the Declaration had come into being, and saying, ‘I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.’ As President, he continued to appeal to the Declaration and the equality clause as a gauge of what was transpiring and what was at stake,” wrote historian Douglas L. Wilson. “In its third year he characterized the Civil War as, at bottom, ‘an effort to overthrow the principle that all men were created equal,’ and, underlining this, he pointed out how fitting it was that on the triumphant Fourth of July 1863 ‘the cohorts of those who opposed the declaration that all men are created equal ‘turned tail’ and ran.'”59

“In every crisis he sought the advice, not of his enemies, but of his friends. To his convictions he was ever true, but his opinions were always subject to revision,” wrote newspaper editor John W. Forney after the war.60 But it was always Mr. Lincoln who made the final decisions. “It was clear to men in Washington that even amid reverses, Lincoln revealed a steady augmentation of self-confidence and decision,” wrote historian Allan Nevins in The War for Union, The Emancipation Proclamation had enhanced his prestige. He had fully established his personal and Presidential authority. As he had defeated Seward at the outset, so now he had defeated the Congressional radicals by compelling them to revise their confiscation Act, and drop their intended reorganization of the Cabinet. He knew how far to trust Stanton, whose brutal temper seldom impaired a sound judgement and an unshakable devotion to the cause. He knew how to see Chase, whose Presidential ambitions, as he said, were like a horsefly on an ox, keeping him up to his work. A Lincoln legend was gaining currency: the legend, as John W. Forney put it, of a great, peculiar, mysterious man who with quaint sagacity did his work in his own honest way without regard to temporizers or hotheads.61

EMANCIPATION

To win the war, free the slaves, and reunite the nation, President Lincoln undertook a series of extraordinary steps – such as suspension of habeas corpus, trial of civilians by military courts, institution of the draft, and forms of warfare that were destructive to private property – which would have been previously unthinkable to him. Even the Emancipation Proclamation was taken as an act to preserve the Union. Although the President often consulted with others, some important steps like the Emancipation Proclamation and the reinstatement of George McClellan as head of the Army of the Potomac – were essentially done by the President alone.

Mr. Lincoln came to believe that the war powers of the President should be broadly construed. “Emancipation was for him ‘a practical war measure’ and as soon as military circumstances at the front seemed to require it and political circumstances in the border states seemed to permit it, Lincoln acted to end slavery in the Confederacy,” wrote Lincoln historian Mark E. Neely, Jr.. “Lincoln did worry more about the consequences of emancipation than the consequences of suspending the writ of habeas corpus – and for good reason. Lincoln regarded the suspension of the writ as an exception for a temporary emergency, and he felt sure that the American people would never want to continue the condition when the emergency was over. He put it more vividly, of course, comparing such an unimaginable course to that of a man fed emetics in illness and then insisting on ‘feeding upon them the remainder of his healthful life.'”62

During President’s Lincoln’s administration, emancipation proceeded gradually and ineluctably toward ultimate passage of the Thirteenth Amendment that constitutional ended slavery in January 1865. This progress was a natural outgrowth, according to historian Harry V. Jaffa, from principles that Mr. Lincoln espoused during the Lincoln Douglas debates and his refusal in the months before his inauguration to compromise on that opposition to the expansion of slavery to American territories. Refuting those historians who detected inconsistency in Mr. Lincoln’s positions, Jaffa noted that “in June 1862, six months after the meeting of the first regular session of the first Congress sitting during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, slavery in the territories of the United States ‘then existing or thereafter to be formed or acquired’ was prohibited. If this constituted an abandonment of the principles of the campaign of 1858, if this was not a consummation of everything Lincoln had fought for that fateful summer, then words have no meaning.”63

“Emancipation by itself ran counter to the President’s policy of enticing Southerners back into the Union through economic means. Lincoln knew that no Rebels were likely to choose the expropriation of billions of dollars worth of their property. He nonetheless took the emancipation road because, over the long run, it was inherent to the American Dream, and therefore slavery he saw as the root evil,” wrote Lincoln historian Gabor Boritt. “More immediately there seemed to be ‘military necessity’: blacks formed the indispensable labor force of the Confederacy, a mainstay of her war effort. The North needed that force. It is also difficult to believe that the Chief Magistrate entirely escaped the sin of hubris, which tempted him to the greatness awaiting the emancipator. Radical political, European diplomatic, and lesser pressures, entered his equation, too. Finally, we should add his perception of the will of God.”64

PROVIDENCE

Mr. Lincoln’s intuitive sense of divine providence pervaded his actions during the Civil War. It was particularly evident in his Second Inaugural Address. “Probably no other speech of a modern statesman uses so unreservedly the language of intense religious feeling. The occasion made it natural; neither the thought nor the words are in any way conventional; no sensible reader now could entertain a suspicion that the orator spoke to the heart of the people but did not speak from his own heart,” wrote Godfrey Rathbone Benson Lord Charnwood, who published his biography of Mr. Lincoln in 1916. “His theology, in the narrower sense, may be said to have been limited to an intense belief in a vast and over-ruling Providence – the lighter forms of superstitious feelings which he is known to have had in common with most frontiersmen were apparently of no importance in his life. And this Providence, darkly spoken of, was certainly conceived by him as intimately and kindly related to his own life.”65

“Evidence of Lincoln’s growing faith in the Almighty is plentiful during the war years, usually from his own speeches and private letters,” wrote Lincoln biographer Reinhard H. Luthin. “In September, 1863, Lincoln proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving and thanks to the Almighty, to be observed on the coming last Thursday of November. And in October he spoke significant words to members of the Baltimore (old school) Presbyterian Synod. The Reverend Phineas Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, introduced them to the President. Lincoln assured them that he was ‘profoundly grateful’ for any form of support from the nation’s religious bodies. When he assumed the presidency, he told them, ‘I was brought to a living reflection that nothing in my power whatever would succeed without the direct assistance of the Almighty.’ He added, ‘I have often wished that I was a more devout man than I am. Nevertheless, amid the greatest difficulties of my Administration, when I could not see any other resort, I would place my whole reliance on God, knowing that all would go well, and that He would decide for the right.'”66

When black abolitionist Sojourner Truth visited President Lincoln in his office, he showed her a Bible that had been given him by black residents of Baltimore. She told him: “Mr. President, when you first took your seat I feared you would be torn to pieces, for I likened you unto Daniel, who was thrown into the lions’ den; and if the lions did not tear you into pieces, I knew that it would be God that had served you; and I said if He spared me I would see you before the four years expired, and He has done so, and now I am here to see you for myself.”67

Mr. Lincoln was not without prejudice, but his meetings with black leaders were notable, even if infrequent. Indeed, in Mr. Lincoln’s “sphere, the races were separate and unequal. Black observers surely felt the weight of this rigid barrier in their dealings with the man who would become known as ‘the Great Emancipator.’ As historian John Hope Franklin has pointed out: “Lincoln could not have overcome the nation’s strong prejudices toward racial separation if he had tried. And he did not try very hard,” Lincoln writer Harold Holzer noted. “Yet Lincoln counted among his greater admirers the highly regarded missionary for tolerance, Sojourner Truth, and the most influential African-American leader of the century, Frederick Douglass. Both of them testified, in recollections of their meetings with the President, to his tolerance and hospitality.”68

“In all interviews with Mr. Lincoln I was impressed with his entire freedom from popular prejudice against the colored race. He was the first great man that I talked with in the United States freely, who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color, and I thought that all the more remarkable because he came from a state where there were black laws,” wrote Frederick Douglass.69 Delegations, like the group of black Baptist ministers who asked him on August 21, 1863 to allow black military chaplains, were similarly treated with respect. “The object is a worthy one, and I shall be glad for all facilities to be afforded them which may not be inconsistent with or a hindrance to our military operations,” replied Mr. Lincoln. He “could well have ignored the request, since members of their race had little political power, but the President showed little prejudice against them where religion was concerned,” wrote historian Wayne C. Temple.70

There was a similar warm dignity and grace in Mr. Lincoln’s formal spoken and written remarks. Roy P. Basler noted that his words “so transcended the natural limitations of public speech as to infuse it with the simplicity and imagination and music of great poetry.” His writing was neither flamboyant nor grandiose, noted Basler, and “because he had early learned to eschew the illusion of emotionalism – that band of the swayer of multitudes, which sways the hearts of hearer and speaker alike with floods of mere rhetoric, he was able in his greatest moments to strike chords never before touched by oratory.” Mr. Lincoln’s own words continue to strike the “mystic chords of memory.” Basler noted that even a virulent critic of President Lincoln like Edgar Lee Masters noted that “It is his poetical flashes that have stayed his fame against attack.”71

“The fact is, the overwhelming circumstance shaping Lincoln’s presidency was war. He had been willing to risk war rather than let the nation perish,” wrote Civil War historian James M. McPherson. “Although restoration of the Union remained his first priority, the abolition of slavery became an end as well as means, a war aim virtually inseparable from Union itself. The first step in making it so came in the Emancipation Proclamation, which Lincoln pronounced ‘an act of justice’ as well as a military necessity.”72

Even at the war’s end, President Lincoln’s dedication to the war’s successful conclusion was obvious, according to writer Garry Wills. “In the Second Inaugural, Lincoln imagined God performing the kind of harsh wartime act that he was driven to. Blood for blood is rendered in strict accountant’s language: the verb ‘sunk, comes from the scheduling of sinking debts.” Mr. Lincoln had said: “Yet, if God wills that [the war] continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.” Wills concluded: “If anyone thought that Lincoln’s principle of compromise must lead to moral relativism, this came as a strict reminder that justice must be done even in the partial and fumbling ways available to mankind. Otherwise divine punishment would be duly exacted.”73

The war had assumed a key moral as well as political dimension. Emancipation had become non-negotiable after August 24, 1864 when he was tempted to let Republican National Committee Chairman Henry J. Raymond depart on a peace mission to Richmond. “If ever there was a time when Abraham Lincoln would have withdrawn emancipation as a condition of peace, it would have been during that last week of August 1864,” wrote historian David E. Long. “The Raymond commission, however, never became an official document, because by 25 August, when Henry Raymond arrived in Washington and came to the White House, Lincoln had decided that he could not proceed with the plan. The president had met with Secretaries Seward Stanton, and Fessenden and discussed Raymond’s proposition. They had concurred in the opinion that to send a peace commission to Richmond would be worse than losing the presidential contest; it would amount to an ignominious surrender.”74

COMPROMISE AND CRITICS

The time for such a compromise had long passed, and Mr. Lincoln knew it. McPherson argued, “His sense of timing and his sensitivity to the pulse of the northern people were superb. As he once told a visiting delegation of abolitionists, if he had issued the Emancipation Proclamation six months sooner than he did, public sentiment would not have sustained it. He might have added that if he had waited six months longer, it would have come too late. After skillfully steering a course between proslavery Democrats and antislavery Republicans during the first eighteen months of war, Lincoln guided a new majority coalition through the uncharted waters of total war and emancipation filled with sharp reefs and rocks, emerging triumphant into a second term on a platform of unconditional surrender that gave the nation a new birth of freedom.”75

Freedom was at the heart of President’s Lincoln’s appeal for the support of English citizens, argued historian Henry Steele Commager. He wrote that Mr. “Lincoln put the case of the Union on the highest ground. Here, he said, is a contest not for empire but for freedom, for self-government, for the rights of men. Freemen everywhere, he insisted, had a stake in the preservation of the Union, for that Union was the last best hope of earth,’ and when the workingmen of Manchester – as of London and Birmingham and Coventry – rallied to the Union cause, in the dark days of the war, Lincoln wrote them in proud confidence that ‘a fair examination of history has served to authorize the belief that the past actions and influences of the United States were generally regarded as having been beneficial toward mankind’ and that English support was ‘an energetic and reinspiring assurance of the inherent power of truth and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity and freedom.’ Lincoln felt that the Union was fighting for the vindication of the principles and practices of self-government; and that upon the success of its struggle was staked the future of democracy in the Western world for years to come.”76

Unlike critics like Senator Benjamin Wade, President Lincoln had the burden of executive responsibility. One day, Wade tried to convince Mr. Lincoln that General George McClellan needed to be replaced. When the President asked whom should replace McClellan, Wade replied, “Why, anybody.” Mr. Lincoln quickly cornered Wade, saying “Wade, anybody will do for you, but not for me. I must have somebody.”77

Throughout these difficulties, President Lincoln remained the master of the troublesome group of generals, officials and congressmen on whom he depended for support of the Union effort. On July 2, 1864, he “pocket-vetoed” a bill sponsored by Senator Wade and Congressman Henry Winter Davis which would have severely restricted his freedom to direct Reconstruction of the South. President Lincoln, “with a cool indifference that drove his enemies frantic, stuffed the bill in his pocket and let it die, neither signing it nor vetoing it, and not even bothering to argue about the matter, merely saying offhand that there was no time for him to study it properly or give it his decision before Congress adjourned,” wrote Lincoln historian Lloyd Lewis. “Again Lincoln had served upon the Radicals and their politician herd that he didn’t want to quarrel with them, but the facts were that he and the people were running the government. What were they going to do about it?”78

“The constraints under which Lincoln felt he must labor were not always recognized by antislavery men, and this gave rise to charges of irresolute policy and wavering commitment. In striving for consent, he would tailor an argument to fit his hearer. To develop public support or outflank opposition, he would at times conceal his hand or dissemble. And he kept his options open,” wrote historian LaWanda Cox. “While such skills added to his effectiveness, they also sowed mistrust and confusion. Similarly misunderstanding arose from his constitutional scruples, which he applied to congressional action as well as his own. Also diminishing the recognition of his leadership was the vanguard position of the Radicals. That he marched behind them should not obscure the fact that Lincoln was well in advance of northern opinion generally and at times in advance of a consensus within his own party.”79

Mr. Lincoln declined to reveal his Reconstruction plans prematurely. He was exceedingly cautious about verbal and written pronouncements – which is why his public speeches during the war were so infrequent. However, his thoughts were often gleaned from meetings with individuals and groups. Writer Nathaniel Hawthorne visited the White House with a group of fellow Massachusetts residents in the spring of 1862. He subsequently wrote an article for the Atlantic Monthly in which he described the visit, but the editor excised his rather unflattering description of President Lincoln. “Immediately on his entrance the President accosted our member of Congress, who had us in charge, and, with a comical twist of his face, made some jocular remark about the length of his breakfast. He then greeted us all round, not waiting for an introduction, but shaking and squeezing everybody’s hand with the utmost cordiality, whether the individual’s name was announced to him or not. His manner towards us was wholly without pretence, but yet had a kind of natural dignity, quite sufficient to keep the forwardest of us from clapping him on the shoulder and asking him for a story,” Hawthorne had written. The group presented Mr. Lincoln with a large whip, made at the factory where they worked. The presenter closed “with a hint that the gift was a suggestive and emblematic one, and that the President would recognize the use to which such an instrument should be put.”80

MAINTAINING COMMAND

Hawthorne noted that “This suggestion gave Uncle Abe rather a delicate task in his reply, because, slight as the matter seemed, it apparently called for some declaration, or intimation, or faint foreshadowing of policy in reference to the conduct of the war, and the final treatment of the Rebels. But the President’s Yankee aptness and not-to-be-caughtness stood him in good stead, and he jerked or wiggled himself out of the dilemma with an uncouth dexterity that was entirely in character.” Flourishing the whip, President Lincoln “accepted the whip as an emblem of peace, not punishment.” Hawthorne noted that the group left in “high good humor,” but with regret that they had not heard the President tell a story. “A good many of them are afloat upon the common talk of Washington, and are certainly the aptest, pithiest, and funniest little things imaginable; though, to be sure, they smack of the frontier freedom, and would not always bear repetition in a drawing-room, or on the immaculate page of the Atlantic.”81

Even with the relief that came from such stories, the strain of the war and the presidency wore on President Lincoln. Biographer Stephen B. Oates wrote of the speech President Lincoln gave from a second floor window shortly after his reelection in November 1864: “One late night, serenaders crowded around the White House with lanterns and banners, and Lincoln stood at a window reading them a statement about what the election meant to him. It meant above all that America’s free institutions could work, that the country could carry out a free canvass in the middle of civil war. Had he abandoned or postponed the election, the rebellion could have well claimed a victory. But by holding the contest, Northerners had saved their free government and proven how strong they still were. And he was glad, he said, that most people had voted for him, the candidate most dedicated to the Union and opposed to treason. He turned away from the window and muttered to [John Hay], ‘Not very graceful, but I am growing old enough not to care much for the manner of doing things.”82

Edward Duffield Neill was a distinguished Minnesota minister and educator who joined the White House staff when William Stoddard got ill in 1864 and continued to serve through the end of the Andrew Johnson administration. He wrote of President Lincoln: “He was independent of all cliques. Willing to be convinced, with a wonderful patience he listened to the opinions and criticism of others. Those whose opinions were not accepted would sometimes charge that he was under the thumb of this or that man, but the sequel always proved that he was not a party tool. While he did not frown, nor stamp his feet, while he eschewed the language of the Janus-faced diplomat, and was slow to reach a conclusion, yet when an opinion was deliberately formed he was as firm as a rock.”83

David Donald, author of Lincoln, noted the changes that President Lincoln made in his Cabinet at the end of his first administration and beginning of his second: “Made over a period of months, these appointments, taken together, offered insight into the likely character of the second Lincoln administration. In contrast to the members of the original cabinet, none of these appointees was a major party leader and none had aspirations for the presidency. Lincoln now felt so strong that he did not have to surround himself with the heads of the warring Republican factions. He did not require ideological conformity of the men he chose; [William] Dennison, [Joseph] Holt, and [James] Speed became more or less affiliated with the Radical wing of the Republican party, but [Edwin] Morgan and [Hugh] McCulloch were strong Conservatives. The President did not want his cabinet members to be rubber stamps, and he was supremely confident of his ability to handle disagreement among his advisers. Unlike his original cabinet, his new appointees – like the holdovers, Seward, Stanton, and Welles – were warmly attached to Lincoln personally. He could now afford the luxury of a loyal cabinet.”84

Mr. Lincoln indulged another luxury in the month before his death – a virtually unprecedented two-week escape from Washington to visit General Ulysses Grant at the Richmond front. While he was moved by a desire to see “his” soldiers, on this occasion, he did so at the suggestion of Grant, who wrote that the “rest would do you good.” According to Civil War historian Bruce Catton, “Long after the war, Grant remarked that a member of his staff had suggested that he invite Lincoln to come down to City Point. ‘I answered that the President was in command of the army and could come down when he wished,’ said Grant. “It was then hinted that the reason he did not come was that there had been so much talk about his interference with generals in the field that he felt delicate about appearing at headquarters. I at once telegraphed Mr. Lincoln that it would give me the greatest pleasure to see him.” It was even more of a tonic for the President, who returned to Washington relatively refreshed and reinvigorated.85

On his return to Washington, the President was bedeviled, however, by suggestions of how he should deal with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. “This talk of Mr. Davis tires me. I hope he will mount a fleet horse, reach the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, and drive so far into its waters that we shall never see him again,” Mr. Lincoln his black messenger, William Slade.86

Hope and tragedy shadowed Mr. Lincoln in the final days of his life. His dreams were morbid. The quotations from Macbeth he repeated during his final trip back to Washington from the war front bore the specter of assassination. On the afternoon he himself was assassinated, President and Mrs. Lincoln went for a carriage ride together. Mr. Lincoln was in such a good mood that his wife told him: “You almost startle me, by your great cheerfulness.” She told artist Francis Carpenter that he replied “And well may I feel so, Mary, I consider this day, the war has come to a close. We must both, be more cheerful in the future – between the war & the loss of our darling Willie – we have both been very miserable.”87

Footnotes

- Walter Lowenfels, editor, Walt Whitman’s Civil War, p. 260.

- John Hay to John G. Nicolay, Washington August 7, 1813 in Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondennce and Selected Writings, p. 49.

- Edward Duffield Neill in Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 601-602.

- Bruce Catton, This Hallowed Ground, p.27.

- Carl Schurz, The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, II, p. 239-240.

- Schurz, II, p. 340.

- John Hope Franklin, “Lincoln and the Politics of War,” in Ralph Newman, editor, Lincoln for the Ages, p. 227.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 279.

- William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South, p. 22-23.

- Paul M. Angle and Earl Schenck Miers, The Living Lincoln, p. 391.

- Isaac Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 203.

- Theodore Pease, editor, Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, p. 559-560.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 404.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men, p. 132.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 211. (From “Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1865.)

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and The War Years, p. 348.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men, p. 112.

- William Herndon and Jesse Weik, Life of Lincoln, p. 423-424.

- Smith Stimmel, Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 96.

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, p. 281. (Illinois Governor Joseph Fifer told this story to Carl Sandburg. Fifer had gotten it from Oglesby. See Carl Sandburg and Paul M. Angle, Mary Lincoln, p. 110-112, and a memo in the Carl Sandburg Papers, University of Illinois, Urbana.)

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, p. 290.

- Herndon and Weik, p. 424.