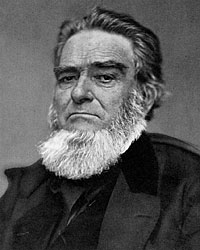

Attorney General under President Lincoln, Edward Bates was somewhat estranged from the rest of the cabinet before his resignation in 1864. In 1860, he was promoted as a candidate for president at the Republican National Convention. His previous support of Know-Nothings, especially in the 1856 presidential race, made him an anathema to German-Americans. His candidacy was pushed by New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley and the Blair family, but opposed by others who thought the Republicans need a younger, more vigorous candidate. He never actually joined the Republican Party and remained an unregenerate Whig who strongly believed in the Union and internal improvements. Conservative by nature and stuffy by temperament, he opposed slavery but disdained blacks. His tenure as Attorney General was notable for the inconsistency of his legal judgements.

Journalist Noah Brooks described Bates as “a small, white haired man, not noticeable in appearance, with a good head, sharp features, and pleasant face well-fringed with gray whiskers. He is not meddlesome in public affairs, lives retired, and, next to Montgomery Blair, is the least influential man in the cabinet.”1 Lincoln scholar Brian McGinty wrote that Bates “was noted for his even, sober disposition.”2 The warmth of Bate’s family life contrasted with the trauma that affected his colleagues. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote that Bates’ “ambitions for political success…had been gradually displaced by love for his wife and large family. Though he had been asked repeatedly during the previous twenty years since his withdrawal from public life to run or once again accept high government posts, he consistently declined the offers.” Goodwin wrote: “The judge’s orderly life was steeped in solid rituals based on the seasons, the land, and his beloved family.”3

Lincoln scholar Frank Williams wrote: “Bates restrained himself to advising the President and the department heads when they had a course of action before them; he would not give general advice or express general legal views on other problems.”4 Williams wrote: “The role of Attorney General in 1861 was a limited job, even if it was one of the four original Cabinet positions. Presidents typically chose their Attorney General with care, but a Department of Justice with a professional staff was still a decade away. Bates was limited to a staff of six, including clerks and messengers. His functions were to give opinions invited by the President or department heads, and to handle government litigation in the Supreme Court. He had no real authority over the United States Attorneys; they were responsible only to the President, who in turn proved too busy to pay much attention to them. They pay and perquisites of the Judiciary Department and the government law offices were largely in the hands of the Interior Department. Most government claims largely rested in the Treasury Department.”5

Unlike some members of Cabinet, Bates maintained a sense of political propriety and did not conspire against the President’s authority. However, in early September he joined the pressure on President Lincoln to block George McClellan from command. Bates observed that Mr. Lincoln seemed so upset that he appeared “almost ready to hang himself” at a September 2, 1862 cabinet meeting.6 Like his colleagues, Bates was furious with the lack of cooperation among Union generals, especially that of George McClellan who had just been appointed to coordinate the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Virginia. “The thing I complain of is a criminal tardiness, a fatuous apathy, a captious, bickering rivalry, among our commanders who seem so taken up with their quick made dignity, that they overlook the lives of their people & the necessities of their country.”7

One of the issues which Bates had to handle for President Lincoln was the issue of military arrests of civilians. According to historian Allan Nevins: “By 1862 the lengthening roll of prisoners, the irritation of the public and Congress, and the demands of military leaders, made it imperative for Attorney-General Bates to take some action. General Buell laid the problem squarely before him. Bates in reply tried to draw a law between judicial arrest on one side, and political or military arrests on the other, saying the judicial cases must go to the civil courts, but the others were subject to the ‘somewhat broad, and yet undefined, discretion of the President, as political chief of the nation’ and commander in chief. The Attorney-General wisely decided that the Department of Justice had no powers in connections with prisoners held on political or military grounds, for it could deal only with offenses against clear Federal statutes.”8

Bates and Postmaster General Montgomery Blair defended the relationships among cabinet members at a December 1862 confrontation with angry Republican members of the Senate who were seeking the ouster of Secretary of State Seward. Two months later, he recorded confidentially to his diary his own complaints about administration actions in his home state of Missouri: “In fact, for some time I have not recd. the consideration which I thought my due, especially in regard to Mo. Affairs—and also, some matters proper to my own office—I do not doubt the [President’s] personal confidence, but he is under constant pressure of extreme factions and of bold and importunate men, who taking advantage of his amiable weakness, commit him beforehand to their ends, so as to bar all future deliberation.”9 Nearly a year earlier, he had written in his diary: “The President is an excellent man, and in the main wise, but he lacks will and purpose, and, I greatly fear, has not the power to command.”10

With time, Bates grew more cantankerous. He wrote in his diary: “If I were in [President Lincoln’s] place I would never submit to have the influence of the two most powerful departments, Treasury and War, brought to bear upon the election—against the President and for the aspiring Secretary.”11 Presidential aide John Hay recalled a meeting he had with Bates in which he “talked a long while and very earnestly in deprecation of the present overriding of law and of judicial procedure in the military departments: the leasing of cotton plantations by Treasury agents & all that class of affairs. He seems in a decided and growing frame of discontent at the way things are going. The President says Judge Bates is persuaded and tries to persuade him that the Baltimore Convention was thoroughly Anti Lincoln & though forced to nominate him did every thing else in the interest of the opposition. The worthy old gentleman feels that he has fallen on evil times.”12

When Chief Justice Roger Taney died in October 1864, Bates “looked upon the office as suitable reward for his devotion and service. In the letter in which he informed Lincoln officially of the death of Taney, Bates stated his claims. He said to Lincoln that he wished to ‘recall to your memory…our former conversations in regard to a vacancy on the Supreme bench…I could not desire to close my public life more honorably, than by a brief term of service in that eminent position,” noted historian David M. Silver. “Bates’s request is remarkable because of a proviso which he included: he suggested to Lincoln that he had no desire to occupy the Chief Justiceship more than two or three years ‘and so it would still be within your disposal during your second term. In fact I desire it chiefly—almost wholly—as the crowning, retiring honor of my life.” Bates resigned on November 24, 1864, however, before President Lincoln could appoint Salmon P. Chase as the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice. 13 Helen Nicolay wrote: “The Attorney General, who had cherished hopes of becoming Chief Justice himself, was a good loser and bore the disappointment as a gallant gentleman should.”sup>14

In their Lincoln biography, aides John G. Nicolay and John Hay observed that in 1864, Bates “grew weary, not only of the labors of his official position, but also of the rapid progress of the revolution of which he had been one of the earliest advocates. Before the war he was the eminent of all those Whig lawyers in the South who, while standing by al the guarantees of the Constitution…Although oddly devoted to the cause of freedom and emancipation, he was wedded by constitutional temperament and lifelong habit to the strictest rules of law and precedent. Every deviation from tradition pained him inexpressively. The natural and unavoidable triumph of the radical party in St. Louis politics, and to a certain extent to those of the nation, seemed to him the herald of the trump of doom. He grew weary of it all and expressed to the President his desire for retirement.”15 In his resignation, Bates wrote President Lincoln: “In tendering the resignation of my office of Attorney-General of the United States (which I now do) I gladly seize the occasion to repeat the expression of my gratitude, not only for your good opinion which lead to my appointment, but also for your uniform and unvarying courtesy and kindness during the whole time in which we have been associated in the public service.”16

After Lincoln’s murder, Bates wrote in his diary that “besides a deep sense of the calamity which the nation has sustained, my private feelings are deeply moved by the sudden murder of my chief with and under whom I have served the country, through many difficult and trying scenes, and always with mutual sentiments of respect and friendship. I mourn his fall, both for the country and for myself.”17

Bates was a former State Senator and one-term Whig Congressman (1827-29) who lost a Missouri Senate race to Thomas Hart Benton before returning to state political and judicial posts. He chaired the River & Harbor Convention in Chicago that Abraham Lincoln attended in 1847. During the Civil War, one son Fleming Bates served with the Confederates and another, John C. Bates, served in the Union Army. His youngest son, Charles, spent most of the Civil War at West Point.

Lincoln Scholar Harold Holzer wrote that Bates was invited to Springfield at the end of December 1860 to meet with President-elect Lincoln and Simon Cameron, another possible cabinet member. On the evening of December 30, wrote Holzer, “Bates arrived at 8:30…in time to join Cameron and the president-elect for another two-hour-long ‘general conversation’ in Cameron’s hotel room. Perhaps Lincoln wanted to gauge for himself how two potential cabinet ministers might interact, not only with him, but also with each other.”18

Footnotes

- Noah Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p.136 (March 13, 1863).

- Brian McGinty, Lincoln and The Court, p. 213.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 22

- Frank J. Williams, “‘Institutions are not made, they grow:’ Attorney General bates and Attorney President Lincoln,” Lincoln Lore, Spring 2004, p. 7.

- Williams, “‘Institutions are not made, they grow:’ Attorney General bates and Attorney President Lincoln,” Lincoln Lore, Spring 2004, p. 5.

- James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 533.

- Stephen Sears, Controversies & Commanders, p. 90.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 313.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 280.

- Beale, Diary of Edward Bates, p. 220.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 406.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 220.

- David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court, p. 196.

- Helen Nicolay, “Lincoln’s Cabinet,” The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, March 1949, p. 290.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History,” Volume IX, pp. 343-344.

- (Letter from Edward Bates to Abraham Lincoln, November 24, 1864)

- Beale, Diary of Edward Bates, p. 473 (April 15, 1865).

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861, p. 181

Visit

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

James Speed

Isaac Newton

Edwin M. Stanton

Montgomery Blair

John Hay

Salmon P. Chase

Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Missouri