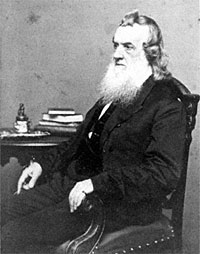

Connecticut Republican leader and a founder of the Hartford Evening Press, Gideon Welles, nicknamed “Father Neptune,” was the Secretary of the Navy from 1861-1869. He was a jealous Cabinet rival of Secretary of State William H. Seward, who he considered meddled in naval affairs. During the 1860 Chicago convention, Welles served as chairman of the Connecticut delegation, in opposition to Seward who had swung many New England votes away from the New York Senator. Seward’s opportunism offended Welles’ stern Puritan morality. He resisted encroachments by other cabinet members on Presidential authority and advocated a tough line toward the English government. A major problem occurred during preparations for the resupply of Fort Sumter.

Welles recorded his confrontation with Seward in his diary, one of the war’s most important documentary records. Very late on the night of April 1, 1861 Seward and his Federick arrived at the Willard to see Welles. They brought with them a telegrams from Captain Montgomery Meigs relating the confusion about the assignment of the U.S. Powhatan, which had been designated for both the relief of Fort Sumter in South Carolina and the relief of Fort Pickens in Florida. Seward’s intervention in these expeditions had resulted in a confusion of orders and telegrams—much to Welles’ consternation. They all decided to take the problem to President Lincoln. Welles wrote:

The President had not retired when we reached the Executive Mansion, although it was nearly midnight. On seeing us he was surprised, and his surprise was not diminished on learning our errand. He looked first at one and then the other, and declared there was some mistake, but after again hearing the facts stated, and again looking at the telegram, he asked if I was not in error in regard to the Powhatan,—if some other vessel was not the flagship of the Sumter expedition. I assured him there was no mistake on my part; reminded him that I had read to him my confidential instructions to Captain Mercer. He said he remembered that fact, and that he approved of them, but he could not remember that the Powhatan was the vessel. Commodore Stringham confirmed my statement, but to make the matter perfectly clear to the President, I went to the Navy Department and brought and read to him the instructions. He then remembered distinctly all the facts, and turning promptly to Mr. Seward, said the Powhatan most be restored to Mercer, that on no account most the Sumter expedition fail or be interfered with Mr. Seward hesitated, remonstrated, asked if the other expedition was not quite as important, and whether that would not be defeated if the Powhatan was detached. The President said the other had time and could wait, but no time was to be lost as regarded Sumter, and he directed Mr. Seward to telegraph and return the Powhatan to Mercer without delay. Mr. Seward suggested the difficulty of getting a dispatch through and to the Navy Yard at so late an hour, but the President was imperative that it should be done.

The President then, and subsequently, informed me that Mr. Seward had his heart set on reinforcing Fort Pickens, and that between them, on Mr. Seward’s suggestion, they had arranged for supplies and reinforcements to be sent out at the same time we were fitting out vessels for Sumter, but with no intention whatever of interfering with the latter expedition. he took upon himself the whole blame, said it was carelessness, heedlessness on his part, he ought to have been more careful and attentive. President Lincoln shunned any responsibility and often declared that he, and not his Cabinet, was in fault for errors imputed to them, when I sometimes thought otherwise.1

Welles was an efficient and conscientious if brusque and stolid administrator who presided over the modernization of the navy. He placed a high value on proper order and procedures as this entry of April 20, 1864 suggests: “The last public evening reception of the season took place last evening at the Executive Mansion. It was a jam, not creditable in its arrangements to the authorities. The multitude were not misbehaved, farther than crowding together in disorder and confusion may be so regarded. Had there been a small guard, or even a few police officers, present, there might have been regulations which would have been readily acquiesced in and observed. There has always been a want of order and proper management at these levees or receptions, which I hope may soon be corrected.”2

Secretary Welles continued to stand up to President Lincoln when he deemed it necessary — although he often confined his criticism to his diary. Historian Craig L. Symonds wrote that “Welles was not merely a yes-man, even when the request came from Lincoln. He occasionally declined to appoint individuals whose names Lincoln forwarded to him, and in particularly he took a much harder line that Lincoln did about naval officers who had trouble decided where their loyalties lay.”3

On July 7, 1863, Welles received a telegram that Vicksburg had fallen to Ulysses S. Grant and brought the news to President Lincoln in his office: “The President was detailing certain points relative to Grant’s movements on the map to Chase and two or three others, when I gave him the tidings. Putting down the map, he rose at once, said we would drop these topics, and ‘I myself will telegraph this news to General Meade.’ He seized his hat, but suddenly stopped, his countenance beaming with joy; he caught my hand, and, throwing his arm around me, exclaimed: ‘What can we do for the Secretary of the Navy for this glorious intelligence? He is always giving us good news. I cannot, in words, tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Welles, it is great!’ We talked across the lawn together. ‘This,’ said he, ‘will relieve Banks. It will inspire me.'”3

Welles’ critical attitude extended to cabinet meetings about which he repeatedly complained in his diary because of their irregularity and informality. He generally disapproved of how most other cabinet members behaved, in their departments and in cabinet meetings. A typical entry was made on June 24, 1864, shortly before Secretary of the Treasury Chase was dismissed from the cabinet:

The President was in very good spirits at the Cabinet. His journey has done him good, physically, and strengthened him mentally and inspired confidence in the General and army. Chase was not at the Cabinet-meeting. I know not if he is at home. But he latterly makes it a point not to attend. No one was more prompt and punctual than himself until about a year since. As the Presidential contest approached he has ceased in a great measure to come to the meetings. Stanton is but little better. If he comes, it is to whisper to the President, or take the dispatches or the papers from his pocket and go into a corner with the President. When has no specialty of his own, he withdraws after some five or ten minutes.

Mr. Seward generally attends the Cabinet-meetings, but the question and matters of his Department he seldom brings forward. These he discusses with the President alone. Some of them he communicates to me, because it is indispensable that I should be informed, but the other members are generally excluded.4

Welles himself was the subject of some of Mr. Lincoln’s bemusement on account of the seriousness of his demeanor Welles is “kind-hearted, affable and accessible man,” noted journalist Noah Brooks. “He is tall, shapely, precise, sensitive to ridicule, and accommodating to the members of the press, from which stand-point I am making all of these sketches. That he is slightly fossiliferous is undeniable, but it is a slander that he is pleaded, when asked to personate the grandmother of a dying sailor, that he was busy examining a model of Noak’s ark; albeit, the President himself tells the story with great unction.” 5

Welles often used his diary to record his disagreements with Secretary of State Seward regarding naval and diplomatic issues. Welles wrote that in March 1864, he was summoned to the White House on a Saturday morning “and as I entered the room, he remarked that I would probably be surprised to hear that Seward already had an application for Letters of Marque. I acknowledged I was disappointed if there were respectable and responsible parties to engage in the business. The President said he knew nothing of the gentlemen whom Seward had brought him, further than that he had a vessel, and was anxious to enter upon the service. Taking up and looking at a paper, he said the gentlemen’s name was Seybert, that he had a vessel of one hndred [sic] tons in which he proposed to put a service, – that this gentleman was then in the audience room, and he would call him in that I might examine him. This I informed him was unnecessary, for I was familiar with the case which had been several times before me. There was, I assured the President, no New York merchants or capital in this enterprise. Seybert was I had learned, a Prussian adventurer, a citizen of South Carolina, and I preferred that the Secretary of State should dispose of this and all other similar applications. With a twinkle in his eye the President said he certainly would not trouble me further in this instance.” 6

Gideon Welles wrote after one cabinet meeting in January 1864 : “Conversation was general, with anecdotes as usual. These are usually very appropriate and instructive, conveying much truth in few words, well, if not always elegantly, told. The President’s estimate of character is usually very correct, and he frequently divests himself of partiality with a readiness that has surprised me.”7

Welles, a onetime Democrat, had earlier served as Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing in the Navy Department under President [James] Polk; during that period he became good friends with the Blair family. Welles was the New England representative in the Lincoln cabinet, but he was not sure of his appointment until President Lincoln submitted to the Senate for confirmation. Welles had met Mr. Lincoln when he visited Hartford in March 1860. Lincoln Scholar Harold Holzer wrote: “Gideon Welles, unable to journey west from Connecticut to stake his own claim – or perhaps, to his disappointment, uninvited – mounted his campaign for the New England cabinet appointment from afar. Although Welles would later claim, quoting the president, that Lincoln had decided to appoint him as early as Election Night, surviving written evidence suggests that he had a far harder time winning a spot.”6 Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “Lincoln, fearing that Welles might be too radical an opponent of the Fugitive Slave Act, had Hamlin investigate that matter; the vice-president-to-be interviewed Connecticut Senator James Dixon, who vouched for Welles’s soundness on the issue.”8

Welles was fortunate to have as an assistant secretary of war, Gustavus Fox, who was both an able administrator and often personally closer to Lincoln than Welles himself. Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana wrote that Welles was “a very wise, strong man. There was nothing decorative about him; there was no noise in the street when he went along; but he understood his duty and did it efficiently, continually, and unvaryingly.”9

Later, Welles supported President Andrew Johnson during Reconstruction. Welle’s wife, Mary Jane, who had lost six children of her own, was a rare good friend of Mary Todd Lincoln. Although sick with a heavy cold, she spent the night of Mr. Lincoln’s assassination and the following day with Mrs. Lincoln.

Footnotes

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 23-25.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 15.

- Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p.54.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 364-365.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 58.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 48.

- Welles, Gideon Welles Diary, Volume I, p. 506 (January 9, 1864)

- Muriel Bernitt, editor, “Two Manuscripts of Gideon Welles,” New England Quarterly, September 1938, p. 604.

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861, p. 209.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume I, p. 744.

- Charles A. Dana, , Recollections of the Civil War, p. 170.

Visit

John Dahlgren

David Dixon Porter

Gustavus V. Fox

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

William H. Seward

First Iron-Clad Monitor

Abraham Lincoln and Connecticut

Navy Department

David Glasgow Farragut

Samuel F. Du Pont

Abraham Lincoln and Cotton

Abraham Lincoln and William H. Seward

The Cabinet (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)