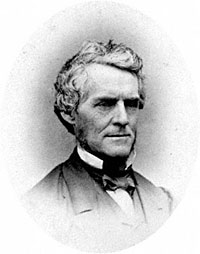

Governor of Ohio (Republican, 1860-62) who strongly supported President Lincoln’s war policies, William Dennison lost renomination because of personal unpopularity. William B. Hesseltine, who wrote a study of Civil War governors, described him as “a man of suavity, of elegant manners and of excellent social connections. Governor Dennison had won a fortune in banking and in railroad operations, and had a reputation for financial ability.” Without much previous political experience, he had problems organizing state government to support the Union effort. “Certainly Dennison was no military expert. The first call for troops found him utterly confused. He accepted regiments without discrimination, commissioned colonels without keeping account of their number, and soon found that he had raised twice as many men as were called from Ohio. Moreover, his inefficient assistants, not knowing what to do with the men, had quartered them in Columbus hotels at a dollar and a quarter a day.”1

Dennison , however, was given one important military task by President Lincoln. He was charged in March 1862 by President Lincoln with informing General George B. McClellan that he had been relieved of overall command of the Union armies and that his duties were henceforth confined to the Army of the Potomac. McClellan, however, declined to see Dennison and therefore only learned of his demotion from the newspapers. Dennison’s loyalty to President Lincoln is illustrated by a story told by historian William Ernest Smith: Francis Blair, Sr., and “Governor Dennison, the excellent war governor of Ohio, an ardent admirer of Lincoln, called on Secretary Welles on the evening of January 10 [1864] to feel him out on the presidential race. Welles was somewhat taken aback to learn that they were not certain of him, but he confessed in his diary that he had been quiet on that subject. His distinguished visitors told him how unjust were the current attacks on the Navy Department and departed satisfied, no doubt, that Welles was safe. They very probably spent the night at Montgomery Blair’s home, since Dennison frequently stayed there overnight. Both of them were closeted with the President the next day.”2

Dennison chaired Republican National Convention in 1856 and 1864. The day after the 1864 Republican Convention, “the committee appointed by the convention to wait upon the President and notify him of his nomination was received in the East Room of the White House, and Ex-Governor Dennison of Ohio, president of the convention, made a very good little speech, and presented Lincoln with an engrossed copy of the resolutions adopted by the convention,” recalled journalist Noah Brooks.3 Another participant recalled: “Mr. Lincoln received us in the East room; and, standing at one side of the room, not at the end, while we formed a semicircle before him, he put on his spectacles and, drawing a manuscript from his pocket, read his little speech of acceptance.”4 Brooks wrote: “The President appeared to be deeply affected by the address, and with considerable emotion and solemnity accepted the nomination in a short speech, in which he referred to pending propositions of amnesty, and to such an amendment to the Constitution as became a fitting and natural conclusion to the final success of the Union cause. His last words, referring to the amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery, were: ‘Now, the unconditional Union men, North and South, perceive its importance and embrace it. In the joint names of Liberty and Union, let us labor to give it legal form and practical effect.”5

Dennison’s loyalty to President Lincoln was rewarded when he was chosen to replace his friend Montgomery Blair as Postmaster General on September 24 1864; Dennison was on the campaign trail for the President in Ohio when he was named. Because Salmon Chase has resigned a few months earlier, it was logical to seek another Ohio representative for the Cabinet. Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher observed of Dennison:

He supposed that it was his duty to attend to the wishes of persons who arrogated to themselves the claim of being genuine and Simon-pure Republicans. There were great numbers of that particular class of people sojourning in and about Washington, claiming greater or less degree to dictate as to who should have office. An aged gentleman by the name of Allison was postmaster at Georgetown, at the time. He was an old citizen of the district, mayor of Georgetown, and respected by all but these newcomers.

They conceived the idea of having Allison removed, and accordingly lodged with Dennison on a ponderous petition praying for his removal. The governor brought it with him to a cabinet meeting and apparently was about to submit it for consideration. He explained what it was and expressed his ignorance of the usual course of presenting such matters. Thereupon, Mr. Seward said: ‘Well, I know Mr. Allison very well. When I came here as a senator from New York, I wanted a seat in the Episcopal church. The people here considered me an abolitionist and determined among themselves that I should not have a seat in the church. This coming to the knowledge of Allison he came to me and said he owned a pew in the church and that it was at my service, that I should sit there no matter who objected, and I did.’ By this time a broad grin came over the faces of the President and all of us and Mr. Lincoln said: ‘Oh, I know Mr. Allison,’ and Governor Dennis on folded up the papers and that is the last we heard of it. So things went with him as postmaster-general. Whoever sympathized with the rebels were considered as ‘offensive partisans’ and were relieved of office.6

At the final cabinet meeting, Postmaster General Dennison asked President Lincoln: “I supposed, you would not be sorry to have [Confederate leaders] escape out of the country.” Mr. Lincoln responded: “Well, I should not be sorry to have them out of the country; but I should be for following them up pretty close to make sure of their going.”

Dennison resigned in mid-1866 in a political dispute with President Johnson. He subsequently lost a race for Senate to James Garfield. An attorney, Dennison served one term in the Ohio Senate (1849-1850) and developed a strong anti-slavery reputation.

Footnotes

- William B. Hesseltine, “Lincoln’s War Governors,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Volume IV, No. 4, December 1946, p. 183.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 253.

- Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C. in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, pp. 150.

- “Abraham Lincoln: The Thirtieth Anniversary of his Assassination,” (Letter from George William Curtis to R.R. Wright, undated), pp. 107-108.

- Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C. in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, pp. 149-150.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, pp. 388-389.

Visit