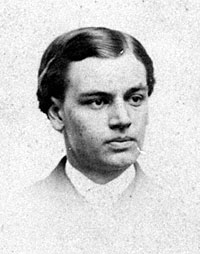

Robert Todd Lincoln, or “Bob” and “Prince of Rails” (a nickname developed on the President-elect’s trip to Washington and one which Robert detested), was named after Mary Todd’s father and was the oldest of the Lincoln children. Cross-eyed as child, he developed into a reserved but determined teenager. He left home at 16 to attend Phillips Exeter and Harvard University. Robert disliked public life although he sometimes liked the public attention he received. Sometime priggish and self-involved, he was emotionally distant from his father, with whom he spent less time as a child than did his brothers. He quickly developed a sense for fashion and clothes that his father lacked. He also had a sense of decorum, which both his mother and father were capable of violating – as when they invited General and Mrs. Tom Thumb for a honeymoon visit to the White House in 1863.

Robert was shy, reserved and fundamentally kind, but he labored under the shadow of his famous and more gregarious father. William O. Stoddard wrote that “Robert Lincoln, the hearty, whole souled and popular ‘Prince of Rails,’ was liked by every one; and by his sincerity of manner, unassuming deportment and general good sense, won a degree of good will and respect that has followed him into private life…His presence, at long intervals, in the White House, was always a pleasant and welcome visitation.” 1

“During the years 1861 to 1865, Robert Lincoln was not only a student, he was a public figure as well,” wrote biographer John S. Goff. “The young man was subjected to almost constant attention from the press and the population in general. This was a difficult position for him, especially as he came more and more to dislike the publicity, Even at this early date a familiar popular notion of this presidential son was beginning to form. If he held himself aloof from the prying gaze of the public, he was haughty and snobbish; if he gave any appearance of capitalizing on his position as the son of the Chief Executive, he was damned for that.”2 Robert’s brief exposure to Washington before the inauguration was altogether pleasant, according to the New York Herald. It reported on March 5, the day after his father’s inauguration: “Bob, the Prince of Rails, starts for Cambridge to-morrow. He is sick of Washington and glad to get back to his college.” The Herald interest in Robert continued to his father’s presidency, later reporting that “He does everything very well, but avoids doing anything extraordinary. He doesn’t talk much; he doesn’t dance different from the other people; he isn’t odd, outré nor strange in any way.”3

Unlike the warm bond enjoyed by his younger brothers, Robert’s relationship with his father was more formal. He later wrote a would-be biographer that “During my childhood and early youth he was almost constantly away from home, attending courts or making political speeches. In 1859 when I was sixteen and when he was beginning to devote himself more to practice in his own neighborhood, and when I would have both the inclination and the means of gratifying my desire to become better acquainted with the history of his struggles, I went to New Hampshire to school and afterward to Harvard College, and he became President. Henceforth any great intimacy between us became impossible. I scarcely even had ten minutes quiet talk with him during his Presidency, on account of his constant devotion to business.”4

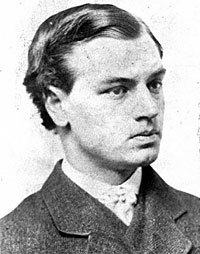

Much criticized for not earlier entering the Union Army, Robert interrupted Harvard law school to serve briefly on General Ulysses S. Grant’s staff in 1865. He and his parents battled over his desire to serve in the Army. Robert’s failure to serve led to criticism from even the President’s political allies. When Senator Ira Harris pressed Mary Lincoln on the question, in 1863, she replied: “Robert is making his preparations now to enter the Army; he is not a shirker – if fault there be it is mine, I have insisted that he should stay in college a little longer as I think an educated man can serve his country with more intelligent purpose than an ignoramous.”5 Seamstress Elizabeth Keckley wrote:

Robert would come home every few months, bringing new joy to the family circle. He was very anxious to quit school and enter the army, but the move was sternly opposed by his mother.

‘We have lost one son, and his loss is as much as I can bear, without being called to make another sacrifice,’ she would say, when the subject was under discussion.

‘But many a poor mother has given up all her sons,’ mildly suggested Mr. Lincoln,’ and our son is not more dear to us than the sons of other people are to their mothers.’

‘That may be; but I cannot bear to have Robert exposed to danger. His services are not required in the field, and the sacrifice would be a needless one.’

‘The services of every man who loves his country are required in this war. You should take a liberal instead of a selfish view of the question, mother.’6

Mary’s half-sister, Emilie Todd Helm, recalled a conversation in which Mary told her husband: “I know that Robert’s plea to go into the Army is manly and noble and I want him to go, but oh! I am so frightened he may never come back to us!’ President Lincoln replied: “Many a poor mother, May, has had to make this sacrifice and has given up every son she had – and lost them all.'”7

Robert had suffered one loss already – in the summer of 1863 when the daughter of the Prussian minister to Washington got married. John Hay wrote John Nicolay that “Bob was so shattered by the wedding of the idol of all of us, the bright particular Teutonne, that he rushed madly off to sympathize with nature [the White Mountains of New Hampshire] in her sternest aspects.”8

On the day President Lincoln was assassinated, Captain Robert Lincoln breakfasted with the family. After Robert showed the President a picture of General Robert E. Lee, Mr. Lincoln told Robert: ” ‘It is a good face; it is the face of a noble, noble, brave man. I am glad the war is over at last.’ Looking up at Robert, he continued: ‘Well, my son, you have returned safely from the front. The war is now closed, and we soon will live in peace with the brave man that have been fighting against us. I trust that the era of good feeling has returned with the war, and henceforth we shall live in peace. Now listen to me, Robert: you must lay aside your uniform, and return to college. I wish you to read law for three years, and at the end of that time I hope that we will be able to tell whether you will make a lawyer or not.” His face was more cheerful than I had seen it for a long while, and he seemed to be in a generous, forgiving mood,” wrote Elizabeth Keckley.9 Robert had to assume the lead role for the family in his father’s funeral – since his mother was completely prostrated by the assassination. Presidential aide Edward Duffield Neil later wrote that “his manly bearing on that trying occasion made me feel that he was a worthy son of a worthy father.”10 On April 21, 1865, Robert resigned his short-lived commission in the army.

Robert disclaimed any influence on his father. “I was a boy occupied by my studies at Harvard College, very seldom in Washington, and having no exceptional opportunity of knowing what was going on,” he later wrote Pennsylvania journalist Alexander K. McClure. Biographer John S. Goff maintained, however, that there were several instances “in which the President eldest son was privy to affairs of state or, at least, had what might be called inside information.”11

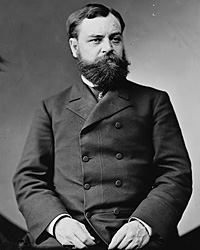

After his father’s death, Robert resigned from the Army and moved with his mother to Chicago where he practiced law. Robert married Mary Harlan in 1868; they had three children, but their only son died as a teenager. His mother’s spending habits led him to have her confined to an insane asylum in 1875. More public-spirited than a public person, he served under Presidents James Garfield and Chester Arthur as Secretary of War (1881-85) and later as Minister to Great Britain (1889-92). His presence at the assassinations of both Garfield and President William McKinley made him self-conscious about “a certain fatality about the presidential function when I am present.” He served as president of the Pullman Company and led a very quiet life prior to his death in 1926, always attempting to preserve and protect the memory of his father.

Biographer Jason Emerson wrote of Lincoln’s first son: “Robert was a disciplined, hard-working man; he was strong, confident and self-aware; he was intelligent, witty, kind, gentlemanly, proper, and generous. Yet he was also impatient: with laziness, with ingorance, with lies and deception, with dishonorable and selfish people; and, once offended, he knew how to hold a grudge, like many of his mother’s family.”12

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame Editor, Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Report of Lincoln’s Secretary: William O. Stoddard, p. 150. (Sketch 2)

- John S. Goff, Robert Todd Lincoln: A Man in His Own Right, p. 39

- Goff, Robert Todd Lincoln: A Man in His Own Right, pp.45-46 (New York Herald, March 5, 1861)

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 292 (New York Herald, undated).

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 499.

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 225.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, pp. 121-22.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 48.

- Keckley, Behind the Scenes, pp. 137-138.

- Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 613.

- Goff, Robert Todd Lincoln: A Man in His Own Right, pp. 53-54.

- Jason Emerson, Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert Todd Lincoln, p. 3.

Visit

John Hay

Thomas D. Lincoln

John Hay’s Office

Guest Bedrooms

James Harlan

Mary Todd Lincoln

Edward Duffield Neill

Biography (Link 2)

Abraham Lincoln’s Sons

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Finance