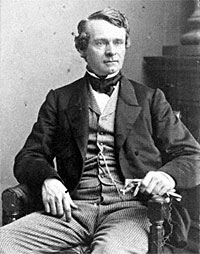

Pennsylvania Governor (Republican, 1861-65), Andrew G. Curtin, was a determined political enemy of fellow Pennsylvanian Simon Cameron and an equally determined supporter of President Lincoln’s war efforts. Curtin was an attorney and advocate of education as secretary of the Commonwealth. He lost the 1854 Senate contest to Cameron, with whom he had long-standing differences on politics, principles, and railroad association—differences which continued for the next two decades. Curtin headed Pennsylvania’s delegation to the 1860 Republican convention, which was pledged to Cameron on the first ballot.

Historian William B. Hesseltine called Curtin “orotund and confused.”1 Contemporaries spoke more kindly. “Circumstance had thrown him into close and confidential relations with Mr. Lincoln, – relations which had their origin at the time of the Chicago Convention, and which had grown more intimate after Mr. Lincoln was inaugurated. Before the firing on Sumter, but when the States of the Confederacy were evidently preparing for war, Mr. Lincoln earnestly desired a counter signal of the readiness on the part of the North,” Congressman James G. Blaine later wrote. “Governor Curtin undertook to do it in Pennsylvania at the President’s special request. On the eleventh day of April, one day before the South precipitated the conflict, the Legislature of Pennsylvania passed an Act for the better organization of the militia, and appropriated five hundred thousand dollars to carry out the details of the measure. The manifest reference to the impending trouble was in the words prescribing the duty of the Adjutant-General of the State in case the President should call out the militia. It was the first official step in the loyal States to defend the Union, and the generous appropriation, made in advance of any blow struck by the Confederacy, enabled Governor Curtin to rally the forces of the great Commonwealth to the defense of the Union with marvelous promptness.”2

Fellow Pennsylvanian Alexander McClure wrote: “I speak advisedly when I say that there was not a single new phase of the war at any time that did not summon Curtin the councils of Lincoln. He was the first man called to Washington after the surrender of Sumter, and I accompanied him in obedience to a like summons to me as chairman of the Military Committee of the Senate. Pennsylvania was to sound the keynote for all the loyal States of the North in the utterance of her loyal Governor, and her action was to be the example for every other State of the Union How grandly Curtin performed that duty is proved by the fact that he organized and furnished to the national government during the war 367,482 soldiers, and organized, in addition to that number, 87,000 for domestic defense during the same period. New duties and grave responsibilities were multiplied upon him every week, but he was always equal to them, and was a tireless enthusiast in the performance of his labors. Three times during the war was his State invaded by the enemy, and at one time 90,000 of Lee’s army, with Lee himself at their head, were within the borders of our State on their way to their Waterloo at Gettysburg. While responding with the utmost promptness to every call of the national government, whether for troops or for moral or political support, he was most zealous in making provision for the defense of his exposed people in the border counties.”3

Curtin’s importance to President Lincoln was heightened by Pennsylvania’s proximity to Washington and the danger which the proximity of Confederate soldiers presented. His problems with Secretary of War Cameron complicated Pennsylvania’s efforts to raise Union troops in the first months of the war. “Curtin raised more than Pennsylvania’s quota, and Cameron refused to accept them. Cameron ordered troops transported over his own rather than Curtin’s railroad. Curtin complained of delays in mustering troops, of inadequate preparations, of lack of equipment. Cameron’s friends charged the governor with corruption on contracts and favoritism in granting commissions,” wrote historian William Hesseltine. Sooner or later, each issue wound up in the White House, where Lincoln, who clearly liked Curtin better than Cameron, steered a cautious course between the contestants.”4

Curtin’s problems with the War Department continued under Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. McClure wrote:

Curtin’s relations with Stanton were never entirely cordial and at times embarrassing; but Lincoln always interposed when necessary, and almost invariably sustained Curtin when a vital issue was raised between them. The fact that Lincoln supported Curtin against Stanton many times greatly irritated the Secretary of War, and doubtless intensified his bitterness against the Pennsylvania War Governor. In one notable instance only, in which Curtin and Stanton were in bitter conflict, did Lincoln hesitate to sustain Curtin, but Lincoln was overruled by his military commanders and bowed to their exactions with profound reluctance. In the winter or early of 1864, Curtin, always alive to the interests of humanity, and feeling keenly the sorrows of the Pennsylvania soldiers who were in Southern prisons pens suffering from disease and starvation, went to Washington three different occasions and appealed to both Stanton and Lincoln for the exchange of prisoners as the Southern commissioners proposed. We then held about 30,000 Southern prisoners, and the South held as many or more of Union soldiers, and General Grant, looking solely to military success, peremptorily refused to permit the exchange of these men, because Lee would gain nearly 30,000 effective soldiers, while most of the 30,000 Union prisoners would be unfit for service because of illness. On Curtin’s third visit to Washington on that subject he was accompanied by Attorney-General William M. Meredith, and they both earnestly pressed upon the government the prompt exchange of prisoners. Stanton grew impatient and even insolent, retorting to the Governor’s appeal: ‘Do you come here in support of the government and ask me to exchange 30,000 skeletons for 30,000 well-fed men?” To which Curtin replied with all the earnestness of his human impulses: ‘Do you dare to depart from the laws of humane warfare in this enlightened age of Christian civilization?” Curtin and Meredith carried their appeal to Lincoln, who shared all of Curtin’s sympathies for our suffering prisoners, and who exerted himself to the utmost, only to effect a partial exchange.”4

Curtin reported to President Lincoln after his visited the Fredericksburg battlefield on December 15, 1862. Curtain lamented that it was a “Slaughter-pen! It was a terrible slaughter, Mr. Lincoln.” He recalled saying: ”Many of the wounded still lack attention and many of the dead are still unburied. From the bottom of my heart I wish we could find some way of ending this war.” After Curtin spoke, Mr. Lincoln said: “Yes, Curtin, it’s a pretty big job we’ve got on hand. It reminds me of what once happened to the son of a neighbor of mine out in Illinois. IN the old man’s orchard was an apple tree of which he was especially choice, and one day in the fall his two boys, John and Jim, went out to gather the apples from this tree. John climbed the tree to shake the fruit off, while Jim remained below to gather it as it fell. There was a boar, which the old man had imported from England, grubbing in the orchard and seeing what was going on it waddled up to the tree and began to eat the falling apples faster than Jim could gather them from the ground. This roiled Jim, and catching the boar by the tail eh pulled vigorously, whereat the latter with an angry sqyeal began to snap at Jim’[s] legs. Afraid to let go Jim held on for dear life, until growing weary he called to his brother to help him. John, from the top of the tree, asked what he wanted. ‘I – want you,’ said Jim, between the rushes of the boar, ‘to—come—down—here—and—help—me—to—let—go—of—this—darned hog’s tail.’” Then President Lincoln said to Governor Curtin “that’s what I want of you and the rest. I want you to pitch in and help me let go of the hog’s tail that I have got a hold of.”5

In May 1863, after the Battle of Chancellorsville, Curtin visited the army of the Potomac and learned the extent of the army’s disaffection from commanding general Joseph Hooker. He let President Lincoln know that Hooker’s effectiveness was impaired by the doubts of other generals. In 1863, Curtin announced his retirement for health reasons and was slated for a diplomatic assignment by President Lincoln, who was seeking to end his political difficulties in Pennsylvania. President Lincoln explained his dilemma to Curtin’s supporters: “I’m in the position of young Sheridan when old Sheridan called him to talk for his rakish conduct and said to him that he must take a wife; to which young Sheridan replied: ‘Very well, father, but whose wife shall I take?’ It’s all very well to say that I will give Curtin a mission, but whose mission am I to take?”6

Curtin vacillated on whether to run for reelection in 1863. Alexander K. McClure wrote: “Of Curtin’s renomination there was no doubt whatever if he permitted his name to be used, and it became merely a question how he could retire gracefully. Entrusted with this matter, acting entirely upon my own judgment, I went to Washington, called upon Colonel Forney and told him my mission. I said ‘Senator Cameron will desire the retirement of Curtin because he is his enemy; I desire it because I am his friend; may we not co-operate in bringing it about?’ Cameron was sent for; the matter was presented to him, and he at once said, with some asperity, that ‘Curtin should be got rid of.’ I suggested that if Lincoln would tender to Curtin a foreign mission in view of his broken health, it would solve the difficulty and enable Curtin to retire. To this Cameron agreed, and within half an hour thereafter we startled Lincoln by appearing before him together, accompanied by Forney. It was the first time Cameron and I had appeared before Lincoln to unite in asking him to perform any public act.”7

McClure recalled: “On the 13th of April of [s1863], I bore to him from President Lincoln an autograph letter voluntarily tendering him a first class foreign Mission at the expiration of his Gubernatorial term, if he were willing to accept. That would have been an inviting compliment for one who sought only political advancement, and it promised rest for the weary and broken Governor; but when it was announced that he had been tendered a Mission, and that he would probably withdraw from the Gubernatorial contest, the response came from half a dozen of the leading counties of the State within a week, unanimously instructing for his renomination, and demanding that he should be made the candidate.”8 McClure recalled that Curtin’s health was so broken by the campaign that he was compelled to leave the Legislature in session and journey to sunnier lands to restore his shattered system.”9

The prospect of a Cameron victory may have helped revive Curtin’s health, revitalize his own popularity, and reignite his ambitions for reelection; he won despite the endorsement of his Democratic opponent by Gen. George McClellan. He subsequently chafed at the interference of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in military recruitment and ceased to try to meet the state’s quotas of new soldiers

Curtin’s feud with Cameron continued and he lost several races before serving as Minister to Russia (1869-1872), a post that Cameron held briefly after he resigned as secretary of war in January 1862. Curtin returned to Pennsylvania and eventually served three terms in Congress as a Democrat in the 1880s.

Footnotes

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 391.

- James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congressman from Lincoln to Garfield, Volume I, p 306.

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 258.

- William Hesseltine, “Lincoln’s War Governors,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. IV, No. 4, December 1946, p. 183.

- McClure, AbrahamLincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 259.

- McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War Times, p. 263.

- McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, pp. 262-263

- Alexander K. McClure, The Life and Services of Andrew G. Curtin, p. 18

- McClure, The Life and Services of Andrew G. Curtin, pp. 20-21.

Visit

Simon Cameron

Alexander McClure

Edwin M. Stanton

Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania