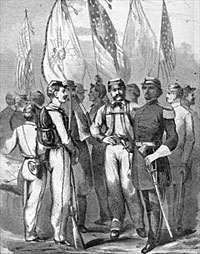

Colonel of Zouaves, Elmer Ellsworth was killed while taking down a Confederate flag in Alexandria, Virginia. Ellsworth was a Chicagoan who was a close friend of President Lincoln’s family and accompanied him on his pre-inaugural trip to Washington. He moved into the White House and played regularly with the Lincoln children. He worked in Lincoln’s law office in August 1860, assisted him during the fall campaign, and had a clerkship with State Auditor Jesse Dubois. The President was unable to fulfill his wish to form a militia bureau in the War Department and appoint Ellsworth to head it as inspector general. In a letter to Secretary Simon Cameron on March 1, 1861 the President wrote about Ellsworth:

“You will favor me by issuing an order detailing Lieut. Ephraim E Ellsworth, of the First Dragoons, for special duty as Adjutant and Inspector General of Militia for the United States, and in so far as existing laws will admit, charge him with the transaction, under your direction, of all business pertaining to the Militia, to be conducted as a separate bureau, of which Lieut. Ellsworth will be chief, with instructions to take measures for promoting a uniform system of organization, drill, equipment, etc. etc. of the U.S. Militia, and to prepare a system of drill for Light troops, adapted for self-instruction, for distribution to the Militia of the several States. You will please assign him suitable office rooms, furniture etc. and provide him with a clerk and messenger, and furnish him such facilities in the way of printing, stationary, access to public records, etc. as he may desire for the successful prosecution of his duties; and also provide in such manner as may be most convenient and proper, for a monthly payment to Lieut Ellsworth, for this extra duty sufficient to make his pay equal that of a Major of cavalry.1

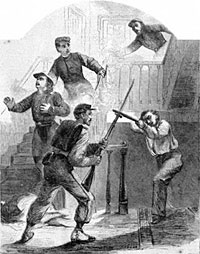

That didn’t work out. “I have been, and still am anxious for you to have the best position in the military which can be given you,” President Lincoln wrote Ellsworth on April 15, 1861.2 Mr. Lincoln did get him a War Department clerkship, which Ellsworth soon resigned. Energetic and charismatic, he developed a keen sense of military discipline and organized the exotically uniformed Zouaves from New York City Fire Department. Ellsworth understood military organization but not office discipline. He was a 19th Century knight in Zouave clothing, delighting in the dramatic. His regiment was instrumental in extinguishing a fire at the Willard’s Hotel on May 9, 1861. Ellsworth’s sense of the theatrical cost him his life in Alexandria when he was shot on May 24, 1861 after pulling down a Confederate flag flying over Marshall House. The President burst into tears at the news of the Union’s first war casualty. ‘Excuse me but I cannot talk. I will make no apology, gentlemen, for my weakness but I knew Ellsworth well, and held him in great regard,” said the President to a Senator who interrupted his grief.3 Mary’s cousin, Elizabeth Grimsley, wrote her family that Ellsworth “was a great pet in the family and Mr. Lincoln feels it very much.”4

Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln both went to the Navy Yard to view Ellsworth’s body. “My boy! My boy! Was it necessary this sacrifice should be!” exclaimed the President.5 Ellsworth’s body was brought back to the White House, where his casket sat in the East Room. The funeral was attended by both Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln and both wept during the ceremonies. Their sons were otherwise employed. Julia Taft wrote that “during the service, I was horrified to see Tad Lincoln and my brother Holly perch themselves on the back of General [Winfield Scott’s] chair. And when he rose, of course they fell back into the arms of some members of his staff. I felt an impulse to tel the President about our pleasant visit to Colonel Ellsworth the day before he was ordered to Alexandria but I was told that the President wept at the mention of Ellsworth and I was afraid it would make him grieve.”6

The President wrote a touching letter to Ellsworth’s parents: “My acquaintance with him began less than two years ago; yet through the latter half of the intervening period, it was an intimate as the disparity of our ages, and my engrossing engagements, would permit…”7 He retained a continuing interest in the welfare of Ellsworth’s father, who was put on the Department of War payroll. Mrs. Lincoln herself made a flower wreath to place on the casket.

Like the rest of the White House residents with whom he was on familial terms, John G. Nicolay was much affected by Ellsworth’s death. He wrote: “I had supposed myself to have grown quite indifferent, and callous, and hard-hearted, until I heard of the sad fate of Colonel Ellsworth. Knowing his ability and his determined energy, I knew that he would win a brilliant success if life were spared him..”8 Nicolay and John Hay considered their young comrade to be like a brother to them. Fellow presidential aide William O. Stoddard later wrote: “The hazy atmosphere of semitragic unreality pervaded at last even the White House itself. The bright spring weather aided the effect of the increasing glitter of uniforms and flutter of flags and all but ceaseless flow and crash of martial music from the noisy bands of the arriving regiments. But now the stark truth had dawned in the death of one man.”9

The flag which Ellsworth had died to tear down was subsequently given to Mrs. Lincoln. Its memory disturbed her and she placed it in a drawer from which Tad Lincoln retrieved it. Occasionally, he would take it out and wave it on official occasions. Once, “when the President was reviewing some troops from the portico of the White House, Tad sneaked this flag out and waved it back of the President, who stood with a flag in his hands. The sight of a rebel flag on such an occasion caused some commotion, and when the President saw what was happening he pinioned his bad boy and the flag in his strong arms and handed them together to an orderly, who carried the offenders within,” wrote Julia Taft.10

Footnotes

- David Mearns, editor, The Lincoln Papers, p. 485-6.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 333.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, p. 262.

- Harry E. Pratt, editor, Concerning Mr. Lincoln, p. 81.

- Randall, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, p. 263.

- Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 38-39.

- Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 385.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 43.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 86.

- Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 39-40.

Visit

John Hay

John G. Nicolay

Family

Elmer Ellsworth (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)