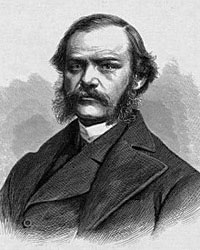

Henry J. Raymond, editor and owner of the New York Times, was a supporter of Abraham Lincoln and close friend of William Seward and Thurlow Weed. He backed Seward in 1860 but helped engineer Lincoln’s renomination at Baltimore Convention in 1864. As an editor, he maintained his editorial independence, cosmopolitan interests and fashionable appearance. When he paid a visit to President Lincoln early in his administration, Mr. Lincoln told him: “I am like a man so busy in letting rooms in one end of his house, that he can’t stop to put out the fire that is burning in the other.”1

Raymond’s editorial policies early in the Lincoln Administration annoyed President Lincoln to the point that Lincoln told Seward that he would deny Raymond the diplomatic position he wanted. According to historian Michael Burlingame, “Seward had been hoping to appoint Raymond consul at Paris, for the editor had grown weary of journalistic drudgery and was eager to serve overseas.”2

Raymond visited the front to determine the military situation for Times’ readers. After one visit in January 1863, he returned to Washington with General Ambrose Burnside. He reported his worries to Administration officials about the Army of the Potomac, particularly those regarding the dictatorial inclinations of General Joseph Hooker. When he encountered President Lincoln at a White House levee, however, the President “put his hand on my shoulder and said in my ear, as if desirous of not being overheard, ‘Hooker does talk badly; but the trouble is, he is stronger with the country today than any other man.”3 Hooker soon replaced Burnside.

Raymond was a natural compromiser and negotiator who had difficulty dealing with Republican Radicals. As Chairman of the Republican National Committee’s Executive Committee, Raymond wavered in support of Lincoln in August 1864 even though he had been primarily responsible for drafting the party’s platform. On August 17, 1864, the New York Times editorialized: “There is not only this great danger of dissension in the Union party, but the Copperheads, it is certain, will attack with greater insidiousness and ranker virulence than ever. They know that this is their last chance. If Mr. Lincoln is reelected, it is certain that the war policy will be maintained, until it is carried through to its legitimate termination.” It concluded: “All true Union men should clearly understand the various dangers which threaten the Union party. Over-confidence is always weak; and, kin this case, it might prove fatal. From now until election, every member of the party should study to promote its harmony, to compact its organization, to fire its spirit. No tolerance should be shown to complaints or croakings; for these always relate to points of minor consequence, without claim when vital concerns are at stake. It has been the deliberate judgment of the Union party, affirmed in regular convention with a unanimity almost unparalleled in such bodies, that Mr. Lincoln, under existing circumstances, is the most expedient candidate for the Union cause. That of itself should be sufficient to enlist for him the earnest support of every true Union man.”4

Raymond expressed his political doubts of the President’s reelectability in letters to former Secretary of War Simon Cameron. He said voters were beginning think that President Lincoln “does not seek peace, that he is fighting not for the Union but for the abolition of slavery.”5 Meanwhile, Henry wrote the president: “I am in active correspondence with your staunchest friends in every state and from them all I hear but one report. The Tide is setting strongly against us. Hon. [Elihu B. Washburne] writes that ‘were an election to be held now in Illinois we should be beaten.’ Mr. Cameron writes that Pennsylvania is against us. Gov. Morton writes that nothing but the most strenuous efforts can carry Indiana. This State (ew York), according to the best information I can get, would go 50,000 against us to-morrow.”6 Raymond was convinced that peace required negotiations; in late August President Lincoln came close to appointing Raymond as a peace commissioner to the Confederacy. Members of the Cabinet dissuaded him. On August 27, after Raymond had met with Lincoln, the New York Times editorialized: “Every member [of the Republican National Committee] is deeply impressed with the belief that Mr. Lincoln will be reelected; and regards the political situation as most hopeful and satisfactory for the Union party.”7

That fall, Raymond was very aggressive in coordinating the Republican reelection drive, raising money from Republican patronage holders and suppliers, and narrowly managing to be elected to Congress himself. He pressured the President to get assistance from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who refused to put pressure on employees of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. A rival New York newspaper wrote that “Raymond walks into the Post Office and Custom House and collects his bills like one having authority.” One form letter to suppliers read: “I take it for granted you appreciate the necessity of sustaining the government in its contest with the rebellion, and of electing the Union candidates in November, the only mode of carrying the war to a successful close, and of restoring a peace which shall also restore the Union.”8

According to artist Francis Carpenter, “A Congressman elect, from New York State, was once pressing a matter of considerable importance upon Mr. Lincoln, urging his official action. ‘You must see Raymond about this,’ said the President (referring to the editor of the New York Times); ‘he is my Lieutenant General in politics. Whatever he says is right in the premises, shall be done.'”9

As an editor and a Republican leader, Raymond favored emancipation but not punitive reconstruction measures. As a congressman, he found himself ostracized from the Republican majority in the House. As an editor, he was a fashionable bellwether for conservative opinion.

Raymond started off as a young assistant to Tribune Editor Horace Greeley, but he eventually became a journalistic and political rival to Greeley. Raymond went on to work for the New York Courier and Express before founding the Times in 1851. A Whig activist, he became a Republican stalwart and served skillfully as speaker of the New York State Assembly. He was Lieutenant Governor of New York and his nomination to that post in 1854 infuriated Greeley, who thought he had a prior claim to it. Raymond’s selection led to Greeley breaking off relations with Seward and Weed.

Footnotes

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years, p. 223.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 144.

- “The Trying Time for the Union Party,” New York Times, August 17, 1864 (www.nytimes.com/books/98/02/15/home/lincoln-trying.html).

- Francis Brown, Raymond of the Times, p. 224.

- Adam I.P. Smith, “Review Essay,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Winter 1999, p. 75 (Letter from Henry J. Raymond to Simon Cameron, August 21, 1864).

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 653 (New York Times, August 27, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 517.

- Reinhold H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 539.

- Henry Raymond, The Life, Public Services, and State Papers of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 758.

Visit

Horace Greeley

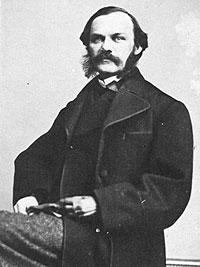

Ambrose E. Burnside

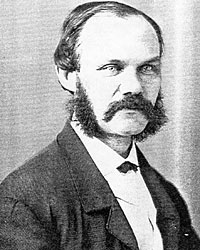

Thurlow Weed

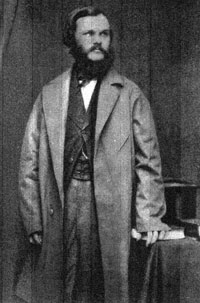

William H. Seward

Elihu Washburne

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Journalists

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and New York)