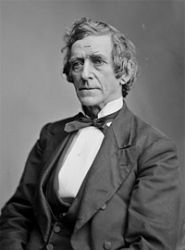

Washington correspondent for the Associated Press for 30 years who covered President Lincoln during the Civil War and reported Lincoln’s assassination. By the Civil War, Gobright was a newspaper veteran and the most experienced journalist in the city, having begun his reporting in Washington in 1834. When he died, the New York Times reported that respected Gobright “was one of the most honest, upright and faithful of men, and during the civil conflict he enjoyed the fullest confidence of President Lincoln and Secretaries Seward and Stanton, often being called upon to assist them in the preparation of proclamations and other important documents which were finally intrusted to his hands for telegraphing.”1 Gobright was a witness to and reporter of many of the important events of Lincoln’s presidency from his inauguration to his death.

President Lincoln was both media-savvy and media-wary, but he tried to maintain a good working relationship with friendly reporters in Washington. The importance that the President placed on cooperation with Gobright was suggested in September 1861, when presidential secretary John G. Nicolay wrote General Benjamin F. Butler asking him to give journalist Lawrence A. Gobright his report “concerning our late victory at Fort Hatteras.”2 In 1863, Gobright was at the White House when President Lincoln asked him to accompany him to the nearby War Department: “I have nothing new. I am much concerned about affairs,” Lincoln told Gobright. “I can’t sleep tonight without hearing something; come, go with me to the War Deparment. Perhaps [Secretary of War Edwin M.] Stanton has something.” When they got a false report about a Union reverse in the siege of Vicksburg, Lincoln said: “Bad news, bad news!” Then he told the reporter: “Don’t say anything about this. Don’t mention it.”3

In an age of opinion journalism, the mutton-chopped Gobright was a purveyor of straight-forward reporting. “My business is to communicate facts; my instructions do not allow me to make any comment upon the facts which I communicate,” he told a congressional committee. “My dispatches are sent to papers of all manner of politics, and the editors say they are able to make their own comments upon the facts which are sent to them ; I therefore confine myself to what I consider legitimate news. I do not act as a politician belonging to any school, but try to be truthful and impartial. My dispatches are merely dry matters of fact and detail. Some special correspondents may write to suit the temper of their own organs. Although I try to write without regard to men or politics, I do not always escape censure.”4

“While Mr. Lincoln was generally courteous to newspaper correspondents, it is not known that he gave to any of them his entire confidence,” wrote Gobright. “Whenever he did impart any item of news, especially relating to events of the war, he was extremely cautious in his narration, so that the exact facts might be stated to the public. As a case in point: On one occasion an important telegram was received at the War Department, announcing a grand Union victory, but for some reason unexplained at the time, the Secretary was not disposed to communicate the particulars. Failing thus to obtain them at the Department, several of the correspondents hastened to the Executive Mansion in order to secure the desired information from the President. The Cabinet meeting had just adjourned, and several of the members were leaving the room. The representatives of the press had no sooner sent in their cards to him than he welcomed them in a loud voice. ‘Walk in, walk in; be seated; take seats.’ Before they had time to announce the object of their visit, he remarked: ‘I know what you have come for; you want to hear more about the good news. I know you do. You gentlemen are keen of scent, and always wide awake.’ One of them replied: ‘You have hit the matter precisely, Mr. President: that’s exactly what we want – the news.'”5

In his memoirs, Gobright recalled Lincoln’s angry response to the premature and mangled publication of his letter to James Conkling – to be read in early September 1863 at a meeting of Union supporters in the President’s home town: “Mr. Lincoln was sometimes distrustful of newspaper people, as the following will show. He had written a political letter to a Springfield (Illinois) Committee, to be read on the meeting of the State Convention. It was known that a copy of the letter was on its way to some other point, to be published when the original should be officially promulgated. The agent of the New York Associated Press at Washington was instructed, if possible, to obtain a copy and forward duplicates by mail. The request was accordingly made of Mr. Lincoln. ‘I can’t do it,’ he said, ‘for I have found that documents given to the press in advance are always prematurely published.’ It was interposed that ‘the Associated Press had never thus promulgated documents before the proper time, and besides, the desire was to avoid mistakes in telegraphing.’ ‘I can’t help that – I have always found what I say to be true.’ ‘Well, Mr. President, it is your own property, and you have a right to dispose of your letter as you choose. Good day.'”

Gobright wrote: “The next forenoon, a second application was made, but with no better success. In the afternoon of the same day, however, I received a telegram from Philadelphia, to the following effect: ‘The Springfield letter of Mr. Lincoln appears in a New York afternoon paper – do you want it ?’ ‘Yes,’ I responded, ‘send me all of it.’ At night the entire letter was received in Washington over the wires, and the next morning appeared exclusively in one of the Washington journals – the paper to which the President was in the habit of first turning his attention. It appeared as if coming from Chicago ; but Mr. Lincoln had not noticed the date. He was sitting comfortably and calmly in his office, when he for the first time saw his letter in print, before it was read in the State Convention, – the same letter which he was so fearful of being published prematurely and for which reason he had declined to furnish it to me”

Rushing into the acting private secretary’s office, he hastily and impatiently inquired how the agent got the copy of his letter – “Who gave it to him?” etc. The questions were asked in such quick succession that the alarmed secretary could merely respond that he didn’t know, but that it was certain he did not obtain it there. Mr. Lincoln returned to his office, wondering “how the thing got out!” He afterward made inquiry, and found that the “premature publication” was made by an enterprising editor, who spread it before his readers nearly a day in advance of its being read at the Springfield Convention. The President was in that case the victim of misplaced confidence; for it was said a copy of the letter had been sent to an editorial friend, not to be published until the proper time.6

Mr. Lincoln had been burned early in his first year by premature leaks of documents from his office. Gobright recalled: “The President, throughout his administration, acted on the fear that his annual messages might, if supplied to the press in advance, find their way into print in advance of delivery; therefore they had to be telegraphed. And the private secretary would not give copies for this purpose, even to the responsible agent of the press, until he had delivered the manuscript documents to the Senate, and the clerk had commenced the reading of them. Notwithstanding the President’s caution, he was repeatedly astonished to find the keen-scented correspondent publishing important matters in advance of the time designated by himself.”7

Gobright was a first-hand witness to Lincoln’s skill as a story-teller. “Mr. Lincoln never would, if he could help it, permit anybody to tell a better story than himself. One day an elderly gentleman called to see him on business – to ask for an office. Before they parted, the President told him a ‘little story.’ It pleased the visitor very much; and their joint boisterous laughter was heard by all in the ante-rooms, and became contagious. The elderly gentleman thought he could tell a better story; and did so. Mr. Lincoln was delighted to hear it, and laughed immoderately at the narration. It was a good one, and he acknowledged that it ‘beat’ his own. The next day he sent for his new friend, on purpose, as it was afterward found out, to tell him a story, a better one than the gentleman had related. The gentleman answered this by a still better than he had previously furnished, and was, thus far, the victor over Mr. Lincoln. From day to day, for at least a week, the President sent for the gentleman, and as often did the gentleman get the advantage of him. But he was loth to surrender, and finally the President told the visitor a story, which the latter acknowledged was the very best he had ever heard. The President thus got even with his friend. He never permitted anybody to excel him in those little jokes.”8

Gobright was also a witness to the President’s charity in dealing with visitors. “Mr. Lincoln extended the Executive clemency to a large number of persons, including those who had slept at their posts,” wrote Gobright, who related several: Three young men were arrested and tried in Baltimore as rebel spies. One of them was from Kent Island, Maryland, but his friends being intensely “Southern,” would or could not take the necessary oath to secure passage to that city in order to inquire into his condition. They, however, at the suggestion of a loyal resident of Washington, who happened to be on Kent Island, wrote a letter to a gentleman here, requesting him to see the President on the subject. – This letter failed to reach its destination, the person to whom it was addressed being out of town. The citizen of Washington, to whom I have just alluded, procured a note of introduction to Mr. Lincoln, and proceeded to the White House with it. While there, a lawyer from Philadelphia came in, and, without much ceremony, began to speak to Mr. Lincoln like an attorney before a magistrate, and he mentioned that another of the young men, his client, was willing to swear that he acted as a rebel letter-carrier only for the purpose of getting away from the South. Mr. Lincoln said this was the first time in his life he had heard of a man’s own oath being offered to save his neck. Mr. Lincoln then looked at my friend, recently returned from Kent Island, as much as to say, “What is your business, sir?” The gentleman remarked, he did not come there as an advocate, but having recently been in that part of Maryland, he found that the people there were intense rebels – thought the President was a tyrant, and utterly denied that the young man was a spy, which they would have been proud to avow if it had been true. My friend said to Mr. Lincoln, he believed the exercise of executive clemency would have a good effect upon the people on Kent Island. Mr. Lincoln replied: “They are hanging our men in Richmond, and there are no persons there interceding for them.” The visitor rejoined, that he did not come there to intercede for the young Marylander; he did not even know him; but had come to tell what he believed to be true. Mr. Lincoln dismissed his visitors with the remark that he wanted to see the proceedings in the case, and could not act until he received them. These were, within a few days, produced. As there was nothing showing positively that the parties were spies, the President commuted their sentence from death to imprisonment in Fort McHenry women, especially elderly women.9 Gobright related one such story:

A young Irishman, who was employed as a fireman on a railroad-train, had been, together with others, engaged in a riot, resulting from the draft; and his mother came to Washington to see Mr. Lincoln in his behalf. She called, and waited at the Executive Mansion during three or four hours, several days in succession. She was successful in procuring an interview. Mr. Lincoln told her to call the next day; when she said that she had lost much time already, and besides, the porter would not let her into his room. “No difficulty about that,” he replied; and he sat down and wrote a ticket of admission; and giving it to her said, “Present this at the door to-morrow, and you will bo admitted.”

She accordingly called the next day, when Mr. Lincoln, touched by the earnestness and eloquence of the old lady, inquired into all the circumstances attending the imprisonment of her son. He took immediate measures to effect the release – to pardon the rioter, much to the joy, of course, of the parent. And he said to her, if she, on her return home, would prepare the proper papers, he would pardon the other rioters. The woman was absent from Washington several months, and when she made her reappearance, Mr. Lincoln recognized her. The petition being in proper form, accompanied by the facts in the case, Mr. Lincoln extended the Executive clemency to the extant he had promised; and the old lady went away happy, showering blessings upon the head of her distinguished friend.10

The 48-year-old Gobright was working late on the night of the assassination of President Lincoln when one of the theatergoers from Ford’s Theater burst into his office: “On the night of the 14th of April, I was sitting in my office alone, everything quiet: and having filed, as I thought, my Ins’ despatch, I picked up an afternoon paper, to see what especial news it contained. While looking over its columns, a hasty step was heard at the entrance of the door, and a gentleman addressed me, in a hurried and excited manner, informing me that the President had been assassinated, and telling me to come with him. I at first could scarcely believe the intelligence. But I obeyed the summons. He had been to the theatre with a lady, and directly after the tragedy at that place, had brought out the lady, placed her at his side in his carriage, and driven directly to me. I then first went to the telegraph office, sent a short ‘special,’ and promised soon to give the particulars. Taking a seat in the hack, we drove back to the theatre and alighted; the gentleman giving directions to the driver to convey the lady to her home.”

Gobright recalled how he came to be in possession of the murder weapon – handed over to him by William T. Kent: “The gentleman and myself procured an entrance to the theatre, where we found everybody in great excitement. The wounded President had been removed to the house of Mr. Peterson, who lived nearly opposite to the theatre. When we reached the box, we saw the chair in which the President sat at the time of the assassination; and, although the gas had for the greater part been turned off, we discovered blood upon it. A man standing by picked up Booth’s pistol from the floor, when I exclaimed to the crowd below that the weapon had been found and placed in my possession. An officer of the navy – whose name I do not now remember – demanded that I should give it to him; but this I refused to do, preferring to make Major Richards, the head of the police, the custodian of the weapon, which I did soon after my announcement. My friend having been present during the performance, and being a valuable source of news, I held him firmly by the arm, for fear that I might lose him in the crowd. After gathering all the points we could, we came out of the theatre, when we heard that Secretary [of State William H.] Seward had also been assassinated. I recollect replying that this rumor probably was an echo from the theatre; but wishing to be satisfied as to its truth or falsity, I called a hack, and my companion and myself drove to the Secretary’s residence. We found a guard at the door, but had little trouble in entering the house. Some of the neighbors were there, but they were so much excited that they could not tell an intelligent story, and the colored boy, by whom Paine was met when he insisted on going up to the Secretary’s room, was scarcely able to talk. We did all we could to get at the truth of the story, and when we left the premises, had confused ideas of the events of the night. Next we went to the President’s house. A military guard was at the door. It was then, for the first time, we learned that the President had not been brought home. Vague rumors were in circulation that attempts had been made on the lives of Vice-President Johnson and others, but they could not be traced to a reliable source. We returned to Mr. Peterson’s house, but were not permitted to make our way through the military guard to inquire into tha condition of the President. Nor at that time was it certainly known who was the assassin of President Lincoln. Some few persons said he resembled [John Wilkes] Booth, while others appeared to be confident as to the identity.”

Gobright recalled: “Returning to the office, I commenced writing a full account of that night’s dread occurrences. While thus engaged, several gentlemen who had been at the theatre came in, and, by questioning them, I obtained additional particulars. Among my visitors was Speaker [Schuyler] Colfax, and as he was going to see Mr. Lincoln, I asked him to give me a paragraph on that interesting branch of the subject. At a subsequent hour, he did Bo. Meanwhile I carefully wrote my despatch, though with trembling and nervous fingers, and, under all the exciting circumstances, I was afterward surprised that I had succeeded in approximating so closely to all the facts in those dark transactions.”11 Gobright’s dispatch read:

President Lincoln and wife, with other friends, this evening visited Ford’s Theatre, for the purpose of witnessing the performance of the ‘ American Cousin.’

It was announced in the papers that General Grant would be present. But that gentleman took the late train of cars for New Jersey.

The theatre was densely crowded, and everybody seemed delighted with the scene before them. During the third act, and while there was a temporary pause for one of the actors to enter, a sharp report of a pistol was heard, which merely attracted attention, but suggesting nothing serious, until a man rushed to the front of the President’s box, waving a long dagger in his right hand, and exclaiming, ‘ Sic semper tyrannic,’ and immediately leaped from the box, which was in the second tier, to the stage beneath, and ran across to the opposite side, making his escape, amid the bewilderment of the audience, from the rear of the theatre, and mounting a horse, fled.

The screams of Mrs. Lincoln first disclosed the fact to the audience that the President had been shot; when all present rose to their feet, rushed toward the stage, many exclaiming, ‘Hang him ! hang him!’

The excitement was of the wildest possible description, and of course there was an abrupt termination of the theatrical performance.

There was a rush toward the President’s box, when cries were heard, ‘ Stand back and give him air!’ ‘Has any one stimulants ?’ On a hasty examination, it was found that the President had been shot through the head, above and back of the temporal bone, and that some of the brain was oozing out. He was removed to a private house opposite to the theatre, and the Surgeon-General of the Army, and other surgeons, were sent for to attend to his condition.

On an examination of the private box, blood was discovered on the back of the cushioned chair in which the President had been sitting; also on the partition, and on the floor. A common single-barrelled pocket-pistol was found on the carpet.

A military guard was placed in front of the private residence to which the President had been conveyed. An immense crowd was in front of it, all deeply anxious to learn the condition of the President. It had been previously announced that the wound was mortal, but all hoped otherwise. The shock to the community was terrible.

At midnight the Cabinet went thither. Messrs. Sumner, Col fax, and Farnsworth; Judge Curtis, Governor Oglesby, General Meigs, Colonel Hay, and a few personal friends, with Surgeon-General Barnes and his immediate assistants were around his bedside. The President was in a state of syncope, totally insensible, and breathing slowly. The blood oozed from the wound at the back of his head.

The surgeons exhausted every possible effort of medical skill, but all hope was gone!

The parting of his family with the dying President is too sad for description. The President and Mrs. Lincoln did not start for the theatre until fifteen minutes after eight o’clock. Speaker Colfax was at the White House at the time, and the President stated to him that he was going, although Mrs. Lincoln had not been well, because the papers had announced that General Grant and they were to be present, and, as General Grant had gone North, he did not wish the audience to he disappointed.

He went to the theatre with apparent reluctance, and urged Mr. Colfax to accompany him; but that gentleman had made other engagements, and with Mr.[George] Ashmun, of Massachusetts, bade him good-bye. When the excitement at the theatre was at its wildest height, reports were circulated that Secretary Seward had also been assassinated.”12

In the wake of the assassination, Gobright was called to testify at the trial of Dr. Samuel Mudd. He also accompanied President Andrew Johnson on the “swing around the circle” tour of the United States in the summer of 1866. In 1869 Gobright compiled his memoirs, Recollection of Men and Things at Washington, During the Third of a Century. Gobright’s AP service came to an end in the summer of 1879 when his work drew criticism from his superiors who forced his retirement.

Footnotes

- “Death of L.A. Gobright After Over 45 Years’ Service,” New York Times, May 15, 1881.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 55 (Letter to Benjamin F. Butler, September 1, 1861).

- Lawrence A. Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, p. 335-336.

- Henry Mills Alden, “Washington News,” Harper’s Magazine, Volume 48, p. 229.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 334.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 337-339.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 348-351

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 330-331.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 333-334.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 331-332.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, p. 348-350.

- Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 348-350.

Visit

Mr. Lincoln’s White House: Ford’s Theater

Abraham Lincoln and Journalists