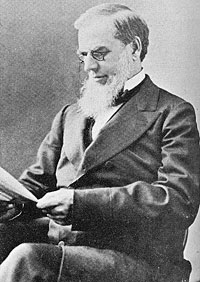

Friend and attorney with whom Lincoln practiced in the Illinois court circuit in the 1850s, Leonard Swett lost the 1856 Republican nomination for Congress to Owen Lovejoy before being elected to the State Legislature in 1858. Swett was a noted criminal lawyer who was one of the originators of the insanity defense. He was also a key organizer of the 1860 Chicago Republican National Convention and the 1864 presidential election. He was defeated in his 1862 bid for election to Congress from the Springfield district by Democrat John Todd Stuart.

Alexander McClure once observed, “Of all living men, Leonard Swett was the one most trusted by Abraham Lincoln.”1 Swett himself said: “It seems to me I have tried a thousand lawsuits with or against Lincoln and I have known him as intimately as I have known any many in my life.”2 In at least one case, the President’s confidence may have been misplaced.

In May 1864, Swett was named by Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher to help oversee a dispute over claims to the New Almaden Quicksilver Mine. Instead of calming passions, Swett managed to inflame them by misrepresenting his instructions to federal authorities in San Francisco—and attempting to use troops to intervene. Relations between Swett and the San Francisco Collector of the Port that President Lincoln had to telegraph them to “consult together and do not have a riot. Swett’s action caused a major Cabinet confrontation in August 1864—in party because General Henry W. Halleck was a part owner of the mine. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase “and his supporters in California, who had no use for party moderates like Usher and [Attorney General Edward Bates], were apparently willing to exaggerate the crisis for potential political advantage. Lincoln had to assure all of these factions that the order had not been surreptitiously obtained and that it did not constitute a change in public land policy,” wrote Usher biographers Elmo R. Richardson and Alan W. Farley.3

He and President Lincoln had several discussions about the election of 1864 in which Mr. Lincoln “never for a moment doubted his second nomination. One time in his room, disputing as to who his real friends were, he told me if I would not show it he would make a list of how the Senate stood when he got through. I pointed out some five or six that I told him I knew he was mistake in. Said he: ‘You may think so, but you keep that until the Convention and tell me then whether I was right.’ He was right to a man. He kept a kind of account book of how things were progressing for a few months, and whenever I would get nervous and think things were going wrong, he would get out his estimates and show how everything in the great scale of action, the resolutions of legislatures, the instructions of delegates, and things of that character, was going exactly as he expected. These facts with many others of a kindred nature have convinced me that he managed his politics upon a plan entirely different from any other man the country has ever produced. It was by ignoring men, and ignoring all small causes, but by closely calculating the tendencies of events and the great forces which were producing logical results.”4

Swett also observed how the President handled pardons. “His mind was full of tender sensibilities. He was extremely human, yet, while these attributes were fully developed in his character and, unless intercepted by his judgment, controlled him, they never did control him contrary to his judgment. He would strain a point to be kind, but he never strained to breaking,” wrote Swett later. “He would sometimes, I think, do things he knew to be impolite and wrong to save some poor fellow’s neck. I remember one day being in his room when he was sitting at his table with a large pile of papers before him. After a pleasant talk, he turned quite abruptly and said: ‘Get out of the way, Swett: tomorrow is to-day and I must go through these papers and see if I cannot find some excuse to let this poor fellow off.’ The pile of papers he had were the records of court martial of men who on the following day were to be shot. He was not examining the records to see whether the evidence sustained the finding. He was purposely in search of occasions to evade the law in favor of life.”5

Swett was a strong political supporter of Abraham Lincoln who promoted David Davis for Supreme Court at the cost of any of Swett’s own personal political aspirations and at the expense of the aspirations of another Illinois attorney whom Mr. Lincoln may have favored—Orville Browning. (At the very beginning of the Lincoln Administration, Swett unsuccessfully sought appointment as consul to Liverpool.) Swett later said that he, Davis and other Illinois lawyers associated with the Republican Party’s Bloomington faction concluded in 1861 that President Lincoln would appoint Senator Browning. In desperation, Swett decided to go to Washington to try to dissuade Mr. Lincoln and persuade him that he owed his presidency to Davis’s actions at the 1860 Republican National Convention. Swett arrived at the White House “in the morning about seven o’clock—for I knew Mr. Lincoln’s habits well—was at the White House and spent most of the forenoon with him. I tried to impress upon him that he had been brought into prominence by the Circuit Court lawyers of the old eighth Circuit, headed by Judge Davis. Davis. ‘If,’ I said, ‘Judge Davis, with his tact and force, had not lived, and all other things had been as they were, I believe you would not now be sitting where you are.’ He replied gravely, ‘Yes, that is so.'”

After returning to the Willard Hotel, Swett had another idea about how to persuade President Lincoln. Understanding President Lincoln’s difficulties in spreading patronage among his friends and colleagues in Illinois, Swett decided that he would renounce any claims on an appointment for himself. He wrote Mr. Lincoln that he could kill “two birds with one stone” by appointing Davis and that “I would accept it as one-half for me and one-half for the Judge; and that thereafter; if I or any of my friends ever troubled him, he could draw that letter as a pleas in bar on that subject. As I read it Lincoln said ‘If you mean that among friends as it reads I will take it and make the appointment.’ He at once did as he said.”6 According to Davis biographer Willard L. King, the meeting actually took place in August 1861 and “more than a year of uncertainty was to intervene between Swett’s proposal to Lincoln and Davis’s appointment.”7 In return, once he was appointed to the Court, Davis unsuccessfully pressed President Lincoln for a diplomatic post for Swett.

Swett remained a stalwart support of Mr. Lincoln’s reelection—even in the dark days of August, 1864. He wrote about a meeting with the chairman of the Republican National Committee. Henry Raymond “not only gave up, but would do nothing. Nobody would do anything. There was not a man doing anything except mischief. A movement was organizing to make Mr. Lincoln withdraw or call a convention and supplant him. I felt it my duty to see if some action could not be inaugurated. I got Raymond, after great labor, to call the committee at Washington three days after I would arrive here, and came first to see if Mr. Lincoln understood his danger and would help to set things in motion. He understood fully the danger of his position, and for once seemed anxious I should try to stem the tide bearing him down. When the committee met, they showed entire want of organization and had not a dollar of money.”8

President William McKinley recalled a story about Swett’s relationship with Mr. Lincoln: “Mr. Swett had come to Washington at a critical period and called at the White House. President Lincoln asked him when he had arrived in the capital. Swett replied in a general way. Mr. Lincoln repeated the inquiry in such form as to bring from Mr. Swett the information that he had come in by the latest train, about an hour previous. ‘Oh!’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘all right. How are things? If you had been in Washington all day, I wouldn’t ask you. You would have heard so much your opinion wouldn’t be worth anything.’”9

Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “Swett, one of the foremost criminal lawyers of his era, enjoyed immense popularity, for he was charming, magnetic, eloquent, generous, unselfish, entertaining, and a devoted friend. When trying a jury case, Lincoln preferred him as his partner to al others.”10 Historian Harry E. Pratt wrote: “Tall and erect in stature, dignified and commanding in personal appearances, possessing strongly marked features, brilliant black eyes overhung by heavy, bush brows, gifted with a powerful voice, suave manners, as an advocate Swett ‘was one of the most persuasive who ever addressed a jury at the American bar.’”11 Swett’s background had included teaching and playing soldier in the Mexican-American War. He had little success in politics – outside of one term in the State Legislature. Fellow attorney Henry Clay Whitney wrote in his memoirs of Swett:

He was not a profound lawyer but he was a most adroit, ingenious and brilliant advocate; and I personally know, that in a jury case, Lincoln preferred association with him to any other lawyer in the State. Indeed, Lincoln seemed to lean on him, and to say in effect, ‘I am all right now, that Swett is with me.’

The same principle obtained in his statesmanship: – whenever Lincoln got hold of Swett Lincoln would consult him at length, on his policies: and the only reason why he did not honor him with an office (beyond that of Government Director of the Union Pacific Railway) was, because Swett was too near to him: and he was fearful he would be censured; but I have reason to know, that Lincoln thought more of Swett, as a man, than any other man in Illinois during the war.12

Swett’s business affairs, which were intertwined with those of Thurlow Weed, became an embarrassment to President Lincoln. Lincoln scholar Robert S. Eckley wrote that in “1863 and 1864, he spent the vast majority of his time in Washington or on his California assignment. He speculated in the stock market without marked success, handled some legal business in Washington, and attempted to obtain cotton trading authorization, which was slow in coming. Finally, in early 1865, he went to Memphis to trade cotton where his law partner, William Orr, was a Supervising Special Agent for the Treasury.” The death of President Lincoln and the concomitant deterioration of Swett’s professional life led him to relocate from Bloomington to Chicago, according to Eckley: “Swett was still in Memphis on April 14 when Lincoln attended Ford’s theater, where he had gone with Lincoln occasion. Within little more than a month, he had returned to Bloomington and found things had changed: his law partner’s health was broken, the legal practice had been neglected, and the traveling circuit no longer existed. His loyalty to Lincoln had yielded no position and no financial rewards.”13

Swett based his legal practice in Chicago and helped organize the hearing that confined Mary Todd Lincoln to an insane asylum.

Footnotes

- Elwell Crissey, Lincoln’s Lost Speech, p. 296.

- Walter B. Stevens, A Reporter’s Lincoln, p. 34.

- Elmo R. Richardson and Alan W. Farley, John Palmer Usher: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Interior, p. 43.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editors, Herndon’s Informants, pp. 164-165.

- Emanuel Hertz, The Hidden Lincoln, pp. 299-300.

- Wilson and Davis, editors, Herndon’s Informants, pp. 710-711.

- King, Lincoln’s Manager David Davis, p. 192.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, pp. 235-236.

- Walter B. Stevens, (edited by Michael Burlingame), A Reporter’s Lincoln, p. 90.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume I, p. 331.

- Harry E. Pratt, “The Repudiation of Lincoln’s War Policy in 1862 – Stuart-Swett Congressional Campaign,” pp. 9 from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, April 1931.

- Henry Clay Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln, pp. 87-88

- Robert S. Eckley, “Leonard Swett: Lincoln’s Legacy to the Chicago Bar,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring 1999, p. 33.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

Thurlow Weed

Orville Hickman Browning

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

David Davis

John Todd Stuart

Abraham Lincoln and the Eighth Judicial Circuit

Leonard Swett (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Supreme Court (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)