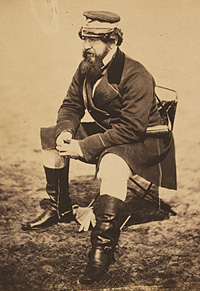

William Howard Russell was the Washington correspondent for the London Times, whose coverage was influential in forming British opinion and who the American government cultivated as a vehicle of communication early in the War. The vain but sensitive journalist was a veteran foreign and war correspondent for the Times when he arrived in America. His critical coverage of the first Battle of Bull Run and the subsequent disorganized retreat contributed to his isolation, however, from the Lincoln Administration and to his return to England in 1862—where he expressed increasingly pro-Union sympathies.

A fellow journalist described Russell at the time: “Short, iron-grey locks parted down the middle, a greyish moustache and a strong tendency to double chin; a very broad and very full but not lofty forehead; eyes of a clear, keen blue, sharply observant in their expression, rather prominently set, and indicating abundant language.”1 Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “Russell was then forty-one, a spectacled, lively, rotund Englishman whose sparkling reports from the Crimean War had made him a celebrity in London.”2

In My Diary North and South, Howard recalled his first interview with President Lincoln, which was arranged by Secretary of State William Seward:

As he advanced through the room, he evidently controlled a desire to shake hands all round with everybody, and smiled good-humouredly till he was suddenly brought up by the staid deportment of Mr. Seward, and by the profound diplomatic bows of the Chevalier Bertinatti. Then, indeed, he suddenly jerked himself back, and stood in front of the two ministers, with his body slightly drooped forward, and his hands behind his back, his knees touching, and his feet apart. Mr. Seward formally presented the minister, whereupon the President made a prodigiously violent demonstration of his body in a bow which had almost the effect of a smack in its rapidity and abruptness, and, recovering himself, proceeded to give his utmost attention, whilst the Chevalier, with another bow, read from a paper a long address in presenting the royal letter accrediting him as ‘minister resident‘; and when he said that ‘the king desired to give, under your enlightened administration, all possible strength and extent to those sentiments of frank sympathy which do not cease to be exhibited every moment between the two peoples, and whose origin dates back as far as the exertions which have presided over their common destiny as self-governing and free nations,’ the President gave another bow still more violent, as much as to accept the allusion.

The minister forthwith handed his letter to the President, who gave it into the custody of Mr. Seward, and then, dipping his hand into his coat pocket, Mr. Lincoln drew out a sheet of paper, from which he rad his reply, the most remarkable part of which was his doctrine ‘that the United States were bound by duty not to interfere with the differences of foreign governments and countries.’ After some words of compliment, the President shook hands with the minister, who soon afterwards retired, Mr. Seward then took me by the hand and said—’Mr. President, allow me to present to you Mr. Russell of the London Times.’ On which Mr. Lincoln put out his hand in a very friendly manner, and said, ‘Mr. Russell, I am very glad to make your acquaintance, and to see you in this country. The London Times is one of the greatest powers in the world—in fact, I don’t know anything which has much more power—except perhaps the Mississippi. I am glad to know you as its minister.’ Conversation ensued for some minutes, which the President enlivened by two or three peculiar little sallies, and I left agreeably impressed with his shrewdness, humour, and natural sagacity.3

Russell’s coverage of the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 dramatically changed the Administration’s attitude toward him. Historian F. Lauriston Bullard wrote: “A month later the mails brought the English paper with Russell’s description of the rout of the first battle of Bull Run. Instantly the North burst into denunciation of The Times and its reporter. There was scarcely a Union paper which did not upbraid Russell.. Anonymous letters threatened him with bowie-knife and revolver. General McDowell, who had commanded the Federals at Bull Run, said laughingly to him: ‘I must confess I am rejoiced to find you are as much abused as I have been….Bull Run was an unfortunate affair for both of us, for had I won it you would have had to describe the pursuit of the flying enemy and then you would have ben the most popular writer in American and I should have been lauded as the greatest of generals.”4

Burned by his Bull Run coverage, Union officials were loath to let Russell anywhere near the battlefront. Russell’s banishment resulted from descriptions of the rout as having no “parallel in any description I have ever read. Infantry soldiers on mules and draught horses, with the harness clinging to their heels, as much frightened as their riders; negro servants on their masters’ chargers; ambulances crowded with unwounded soldiers; wagons swarming with men who threw out the contents in the road to make room, grinding through a shouting, screaming mass of men on foot, who were literally yelling with rage at every halt.”5

Historian Martin Crawford wrote: “Indeed, on the professional level, the critical objectivity that Russell so stubbornly deployed on his American visit was also his greatest burden; as attacks upon his conduct in both the norther and southern states intensified, Russell failed fully to comprehend the nationalistic forces that conspired against him.”6 In 1862, the disdain of the White House was reflected in an anonymous newspaper report “Another of the good things of the week was the expulsion of Russell, the ‘hired man of the London Times,’ from the steamer in which he had embarked himself and luggage. The campaign in Virginia is not to be caricatured by a paid slanderer, while Secretary Stanton has prevented any ill effects of his action by permitting three British officers of high rank to accompany the army. It was a cool way of saying to Dr. Russell, ‘These men are gentlemen, I believe that they will tell the truth about what they may see. We have endured you long enough.’ Russell came back in high dudgeon and appealed to the President, but Mr. Lincoln declined interfering, and the discomfited scribbler threatens to return to England.”7

To Russell’s credit, he was quick to observe the malign influence of “Chevalier” Henry Wikoff, a journalist and social climber who had attached himself to Mrs. Lincoln’s inner circle, and quick to be critical of her appearance and behavior. After an theater visit in November 1861, Russell recorded in his diary: “Went to the Theatre, whole corps diplomatique. Mrs. Lincoln in an awful bonnet facing us & Wikoff in attendance.”8 A few days later, Russell recorded a performer by Hermann the magician at the White House: “At his performance at yet Presidents last night he had a ‘brilliant throng’ as a collection of rowdies is generally styled by Shaw of the Herald. Poor Mrs. Lincoln a more preposterous looking female I never saw. She aped the airs of le monde last night & hid herself behind her gauze curtain peering out now & then only & she was clothed in ye royal ermine whilst yet jail bird Wikoff hovered around in attendance.” Nor was Russell particularly grateful of her attentions: “The story of her sending a bouquet to met is all over Washington & much exaggerated.”9

Footnotes

- John Black Atkins, The Life of William Howard Russell, Volume II, p. 8.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 338.

- Fletcher Pratt, editor, William Howard Russell, My Diary, North and South, pp. 21-24.

- Jay Monaghan, The Man Who Elected Lincoln, p. 247.

- F. Lauriston Bullard, Famous War Correspondents, p. 57.

- Martin Crawford, editor, William Howard Russell’s Civil War: Private Diary and Letters 1861-1862, p. xliv.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 70 (March 31, 1862)

- Crawford, editor, William Howard Russell’s Civil War: Private Diary and Letters 1861-1862, p. 184.

- Crawford, William Howard Russell’s Civil War: Private Diary and Letters 1861-1862, p. 185 (November 23,1861).

Visit

The Journalists (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Journalists

William H. Seward

Chevalier Henry Wikoff