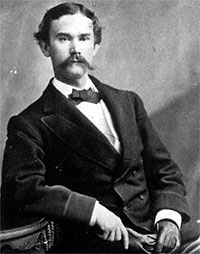

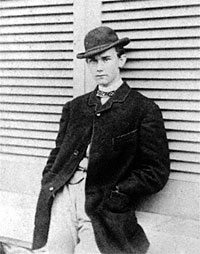

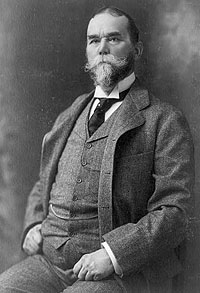

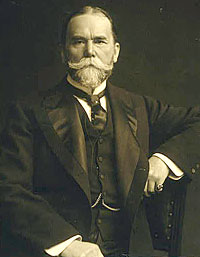

John Hay, the Assistant Private Secretary to Abraham Lincoln, co-authored the 10-volume Abraham Lincoln: A History. He was clerking his uncle’s law office in Springfield in 1859-60 when he came to know President-elect Lincoln. John G. Nicolay, Mr. Lincoln’s secretary, insisted that Hay accompany them to Washington. Mr. Lincoln acquiesced in hiring the youthful graduate of Brown University. During Lincoln’s presidency, Hay was a social companion of Robert Lincoln when the President’s son was in the capital. In 1863 and 1864, Hay served on military missions to South Carolina and Florida and was appointed an army major to investigate an insurrection plot in St. Louis.

Cheerful and convivial, cosmopolitan and debonair, his personality meshed easily with that of his more rustic boss, for whom he was almost a surrogate son. Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “The relationship between Hay and Lincoln was like that which had developed between Alexander Hamilton and George Washington. As the journalist John Russell Young recalled, Hay ‘knew the social graces and amenities, and did much to make the atmosphere of the war[-]environed White House grateful, tempering unreasonable aspirations, giving to disappointed ambitions the soft answer which turneth away wrath, showing, as Hamilton did in similar offices, the tact and common sense, which were to serve him as they served Hamilton in wider spheres of public duty.'”1

Hay’s admiration for the President was almost boundless. He wrote to John Nicolay in September 1863: “The old man sits here and wields like a backwoods Jupiter the bolts of war and the machinery of government with a hand especially steady & equally firm.”2 Because he dined frequently in neighboring hotels with other public figures and socialized in their homes, Hay was in a position to act as an important source of information for the President. He was also a source of humor. According to biographer Tyler Dennett, Hay was “the court jester. [John Forney] once congratulated him on the attitude he was taking toward his work, and remarked that he had ‘laughed through his term.'”3

Once an Illinois correspondent for the Missouri Democrat partly owned by Frank Blair, Hay’s literarytalents were evident in this diary description of September 29, 1863: “Today came to the Executive Mansion an assembly of cold-water men & cold water women to make a temperance speech at the President & receive a response. They filed into the East Room looking blue & thin in the keen autumnal air; Cooper, my coachman, who was about half tight, gazing at them with an air of complacent contempt and mild wonder. Three blue-skinned damsels personated Love, Purity, & Fidelity in Red White & Blue gowns. A few Invalid soldiers stumped along in the dismal procession. They made a long speech at the President in which they called Intemperance the cause of our defeats. He could not see it, as the rebels drink more & worse whiskey than we do. The filed off drearily to a collation of cold water & green apples, & then home to mulligrubs.”4

Other observers were less impressed by the arrogance and self-importance of young aide. Hay was smart and knew it. He was attractive to young women and knew it. He was witty and knew it. Colleague William O. Stoddard recalled an incident interrupted his work to tell a joke. Nicolay heard the laughter and came into the room. The President heard the laughter and joined them: “‘Now John, just tell that thing again’ His feet had made no sound in coming from his room, or our own racket had drowned any footfall, but here was the President, and he sank into Andrew Jackson’s chair, facing the table, with Nicolay seated by him and Hay still standing by the mantel. The story was as fresh and was even better told that third time up to its first explosive place. Down came the President’s foot from across his knee with a heavy stamp on the floor, and out through the hall went the uproarious peal of laughter.”5

The President and Hay even invaded each other’s bedrooms late at night to exchange news and stories. On one occasion, Hay reported: “I went to the bedside of the Chief couché. I told him the yarn; he quietly grinned.” Journalist Noah Brooks, a friend of the Lincoln family, wrote: “Perhaps in all American public life nothing is more charming than the story of the relations which existed between these two men, the one in the bloom of youth, the other hastening toward his tragic end. Lincoln treated Hay with the affection of a father, only with more than a father’s freedom. If he waked at night he roused Hay, and they read together; in summer they rode in the afternoons, and dined in the evenings at the Soldiers’ Home. In public matters the older man reposed in the younger unlimited confidence.” 6

Historian Michael Burlingame wrote that “Hay’s humor, intelligence, love of word play, fondness for literature, and devotion to his boss made him a source of comfort to the beleaguered president in the loneliness of the White House.”7 Hay’s good humor stood him in good stead, but he often clashed with Mrs. Lincoln at the White House—since he and John Nicolay shared responsibility for the White House expense account. Early in the war, he also oversaw White House security. The conflict with the woman he called the “hellcat” hastened his appointment to be a diplomat in Paris in 1865. He had soaked up literature and culture at Brown University; he shared with his White House boss a love of poetry and an occasionally melancholy temperament. He also shared the President’s love of good writing and the theater.

Lincoln chronicler Daniel Mark Epstein wrote that “the secretaries rarely left Washington for rest without an assignment somewhere in the vicinity of their destination, such as Hay’s detour to St. Louis when he went to visit his family in Warsaw, 10 miles away.”8 When Hay was sent to Florida by President Lincoln in 1864, it was rumored that Hay was to become the state’s first reconstruction congressman; reconstruction failed however as did all subsequent efforts to get Hay to run for political office. After the Civil War Hay served as a distinguished poet, novelist, journalist, businessman and diplomat, including service as Ambassador to Great Britain (1897-98) and Secretary of State (1898-1905) under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Hay managed the Open Door Policy toward China, negotiated the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty and helped arrange for construction of Panama Canal.

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864 p. xxiii.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 54.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p.89

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 89.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 166-167.

- Gilson Willets, Inside History of the White House (Brooks Adams)

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 74.

- Daniel Mark Epstein, Lincoln’s Men, p. 69.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

John Hay’s Office

John Nicolay’s Office

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

John Hay’s and John Nicolay’s Bedroom

Ford’s Theater

Blue Room

William H. Seward’s House

George McClellan’s Headquarters

The War Department

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Secretary of State

Abraham Lincoln’s Secretaries

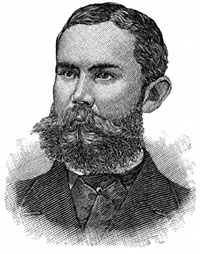

John Nicolay