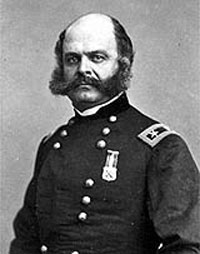

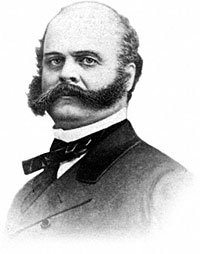

Ambrose E. Burnside, “Burn,” was the General of Army of Potomac, who succeeded George McClellan in November 1862. A failed Rhode Island businessman who designed a rifle later used in the Civil War, he worked for the Illinois Central Railroad under George McClellan when Lincoln was one of the company’s attorneys. Burnside’s slow arrival at Antietam turned a potential Union victory into a draw; nevertheless, he was appointed to head the army after McClellan failed vigorously to pursue the Confederates. He was consumed by self-doubt; he had declined to lead the Army of the Potomac before accepting it on November 7, 1862.

Lincoln reluctantly assented to Burnside’s initial battle plans. Civil War writer Francis Augustin O’Reilly wrote:“Perhaps he relented because of the commander’s conviction and aggressiveness. Confidence like that needed to be encouraged, and Burnside’s zealousness differed refreshingly from the always-whining McClellan. Yet the president still had reservations. ‘The plans of General Burnside,’ wrote Herman Haupt, ‘did not meet with the cordial approval of the President and General Halleck, and their assent was given with reluctance.’ At 11:00 A.M. on November 14, Henry Halleck wired Burnside: “The President has just assented to your plan,’ adding for emphasis: ‘He things it will succeed if you move rapidly; otherwise not.’”1

After the Union defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862, his command of the army was undermined by dissension with subordinates, some of whom went to the White House to complain. In response to a visit by Generals John Newton and John Cochrane, Mr. Lincoln ordered Burnside not to attempt any strategic movements without consulting him. In response, Burnside travelled to the White House and met with President Lincoln in his office on December 31. He explained his plans and suggested that he resign—and that General Henry Halleck and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton do so as well. President Lincoln in turn explained the previous visit from two anonymous generals but refused to reveal their names to Burnside.

At Willard’s Hotel that night, Burnside wrote the President: “It is of the utmost importance you be surrounded, and supported by men who have the confidence of the people, and of the army, and who will at all times give you definite and honest opinions in relation to their separate departments, and at the same time give you positive and unswerving support in your public policy.”2 The next day, January 1, 1863, Burnside met Stanton and Halleck in Halleck’s office and gave the President his letter which included his resignation. Halleck and Burnside both wanted the tale-bearing generals dismissed, but only President Lincoln knew their names. “No definitive conclusion was come to” about military strategy, complained Burnside.3 In particular, Halleck declined to give definitive advice to President Lincoln—but later gave a definitive resignation to Mr. Lincoln which he rejected. In between the meeting and the Halleck resignation, the President signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

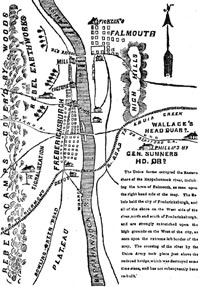

Burnside returned to the army that day and began planning another offensive—while persisting in suggesting his own replacement to President Lincoln. He was stymied by uncooperative weather and uncooperative subordinates. He eventually called off his ill-fated “Mud March” and prepared General Order No. 8 ordering the dismissal of four top generals from the army. After a disastrous and water-logged trip to Washington with Henry Raymond, he arrived at the White House early on January 24. He gave his proposed order to the President— since only the President could issue such orders. The President agreed that Burnside could not continue in office if the order was not issued, but said he needed to consult with Halleck and Stanton. Burnside returned to his headquarters at Falmouth, then returned again to the White House that night. After another night at Willard’s, he went to Mr. Lincoln’s office for a 10 a.m meeting. He was informed that he was to be replaced by Joseph Hooker, one of the generals he had sought to replace. Burnside again returned to Falmouth for the transfer of command of the Army of the Potomac.

Burnside was a loyal and well-meaning, but ill-starred general, whose every move seemed to be thwarted by circumstance. He frequently took aggressive actions that were overruled by superiors. President Lincoln sought another command for Burnside and he was ultimately transferred to command the Department of Ohio in 1863 (where he arrested Clement Vallandigham and defended Knoxville). He was brought back to Virginia in 1864 where he pushed for the mining of Confederate lines which led to the unsuccessful Crater explosion which was meant to break the Confederate line at Petersburg 1864. The failure of the Crater plan, for which several other generals shared blame, led to Burnside’s removal from command. As historian Charles Bracelen Flood observed “The Battle of the Crater ended Ambrose Burnside’s military career.”4

The Rev. Samuel Iraneus Prime, a Presbyterian minister who was editor of the New-York Observer, remembered: “During the war, I was dining with a party of which Gen. Burnside was one. A gentleman expressed surprise and regret that the war had not brought to the front in civil service some man of such commanding force of character, will-power and genius as to compel his countrymen to accept him as the born statesman for the hour. Gen. Burnside said: ‘We are drifting, and it is better so. I think Mr. Lincoln is just the man to keep the ship on its course. One more headstrong, willful and resolute might divide and weaken the counsels of the nation. We shall go through and come out all right.'”5

Burnside was Governor of Rhode Island (1866-68) and a Senator (1875-81).

Footnotes

- Francis Augustin O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock, p. 25.

- William Marvel, Burnside, p. 210.

- Stephen Sears, Controversies & Commanders, pp. 147-148.

- Charles Bracelen Flood, 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History, p. 241.

- Osborn H. Oldroyd, editor, The Lincoln Memorial: Album-immortelles, pp. 285-286 (Samuel Iraneus Prime).

Visit

Joseph Hooker

Henry W. Halleck

Henry J. Raymond

George B. McClellan

Edwin M. Stanton

Biography

Battle of Petersburg

Abraham Lincoln and Ohio

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief