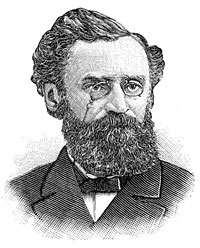

Union Army General Carl Schurz served in the Mountain Department, the Army of the Potomac, and the Mississippi Department. The well-educated and well-cultured Schurz had, what John Hay called “every quality of romance and dramatic picturesqueness.” Schurz helped organize a Union cavalry unit in 1861 before he left to serve as Minister to Spain (1861-62). According to historians Harry J. Carman and Reinhard Luthin, “The problem of caring for Schurz…was most perplexing to Lincoln. ‘Next to the difficulty about Fort Sumter,’ one server in Washington wrote, ‘the question as to what is to be done with Carl Schurz seems to bother the administration more than anything else. Schurz, who later became a crusader for civil service reform, was, in 1861, an indefatigable office seeker, fully appreciative of his own efforts in swinging tens of thousand of naturalized [German] citizens to the Republican standard in the recent campaign.”1

Virtually all diplomatic assignments were rewards for Republican loyalty. Schurz had first been slated for Sardinia, but his revolutionary past convinced Secretary of State William H. Seward that his background would jeopardize his effectiveness. Placing him proved difficult. According to the New York Daily News, “The celebrated Mr. Carl Schurz appears to be a difficult child for the Administration to baptize.”2

Montgomery and Frank Blair helped arrange for Cassius Clay, who had been slated for Spain, to agree to be sent instead to Russia. The result pleased Schurz, who wrote: “Next to Mexico, Spain is the most important diplomatic post – and it is mine.”3 In early 1862, Schurz was granted a leave to return from Madrid to the United States; he wanted an appointment as brigadier general in the army. After a turbulent ocean voyage, Schurz and his family arrived back in America. He wrote in his memoirs:

From New York I hurried at once to Washington, where I first reported to Mr. Seward at the State department. Owing to the presence of some foreign diplomats waiting upon the Secretary, we cut our conversation short with the understanding that we would discuss matters more fully at some more convenient time. I then went to call upon Mr. Lincoln at the White House. He received me with the old cordiality.

After the first words of welcome the conversation turned upon the real reasons for my return to the United States. I repeated to Mr. Lincoln substantially the contents of my despatch of September 18th. I did not deem it proper to ask him whether he had ever seen that despatch, and he did not tell me that he had. But he listened to me very attentively, even eagerly, as I thought, without interrupting me. I was still speaking when the door of the room was opened and the head of Mr. Seward appeared. ‘Excuse me, Seward,’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘excuse me for a moment. I have something to talk over with this gentleman.’ Seward withdrew without saying a word. I remember the scene distinctly. After the short interruption I continued my talk for a while, and when I stopped Mr. Lincoln sat for a minute silently musing. At last he said: ‘You may be right. Probably you are. I have been thinking so myself. I cannot imagine that any European power would dare to recognize and aid the Southern Confederacy if it becomes clear that the Confederacy stands for slavery and the Union for freedom.’ Then he explained to me that, while a distinct anti-slavery policy would remove the foreign danger, and would thus work for the preservation of the Union – while, indeed, it might, in this respect, be necessary for the preservation of the Union, and while he thought that it would soon appear and be recognized to be in every respect necessary, he was in doubt as to whether public opinion at home was yet sufficiently prepared for it. He was anxious to unite, and keep united, all the forces of Northern society and of the Union element in the South, especially the Border States, in the war for the Union. Would not the cry of ‘abolition war,’ such as might be occasioned by a distinct anti-slavery policy, tend to disunite those forces and thus weaken the Union cause? This was the doubt that troubled him, and it troubled him very much. He wished me to look around a little, and in a few days to come back to him and tell him of the impressions I might have gathered. Then he told me how he had enjoyed some of my despatches about Spanish conditions and public men, and how glad he had been to hear from Seward that I was getting on so nicely with ‘the Dons.’ So we parted.”4

Although a “political general,” Schurz served ably in battles such as the Second Bull Run and Gettysburg, but he and German soldiers were scapegoated for the Union defeat at Chancellorsville. He left his military post to campaign for President Lincoln in 1864.

Schurz was ambitious for Germans generally and himself in particular and could be impertinent with superiors. He occasionally disagreed with the President and committed his disagreements to writing. In his autobiography, Schurz recalled how the President responded in November 1862 to Schurz’s repeated critical letters:

Two or three days after Mr. Lincoln’s letter had reached me, a special messenger from him brought me another communication from him, a short note in his own hand asking me to come to see him as soon as my duties would permit; he wished me, if possible, to call early in the morning before the usual crowd of visitors arrived. At once I obtained the necessary leave from my corps commander, and the next morning at seven I reported myself at the White House. I was promptly shown into the little room up-stairs, which was at that time used for cabinet meetings – the room with the Jackson portrait above the mantel-piece – and found Mr. Lincoln seated in an arm chair before the open-grate fire, his feet in his gigantic morocco slippers. He greeted me cordially as of old and bade me pull up a chair and sit by his side. Then he brought his large hand with a slap down on my knee and said with a smile: ‘Now tell me, young man, whether you really think that I am as poor a fellow as you have made me out in your letter!’ I must confess, this reception disconcerted me. I looked into his face and felt something like a big lump in my throat. After a while I gathered up my wits and after a word of sorrow, if I had written anything that could have pained him, I explained to him my impressions of the situation and my reasons for writing to him as I had done. He listened with silent attention and when I stopped, said very seriously: ‘Well, I know that you are a warm anti-slavery man and a good friend to me. Now let me tell you all about it. Then he unfolded in his peculiar way his view of the then existing state of affairs, his hopes and his apprehensions, his troubles and embarrassments, making many quaint remarks about men and things. I regret I cannot remember all. Then he described how the criticisms coming down upon him from all sides chafed him, and how my letter, although containing some points that were well founded and useful, had touched him as a terse summing up of all the principal criticisms and offered him a good chance at me for a reply. Then, slapping my knee again, he broke out in a loud laugh and exclaimed: ‘Didn’t I give it to you hard in my letter? Didn’t I? But it didn’t hurt, did it? I did not mean to, and therefore I wanted you to come so quickly. He laughed again and seemed to enjoy the matter heartily. ‘Well, he added, ‘I guess we understand one another now, and it’s all right.’ When after a conversation of more than an hour I left him, I asked whether he still wished that I should write to him. ‘Why, certainly,’ he answered; ‘write me whenever the spirit moves you.’ We parted as better friends than ever.5

At the end of July 1864, Schurz visited with President Lincoln at the Soldiers Home:

I called upon Mr. Lincoln on a hot afternoon late in July. He greeted me cordially, and asked me to wait in the office until he should be through with the current business of the day, and then to spend the evening with him at the cottage on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, which he occupied during the summer. In the carriage on the way thither he made various inquiries concerning the attitude of this and that public man, and this and that group of people, and we discussed the question whether it would be good policy to attempt an active campaign before the Democrats should have ‘shown their hand’ in their National Convention. He argued that such an attempt would be unwise unless some unforeseen change in the situation called for it. Arrived at the cottage, he asked me to sit down with on a lounge in a sort of parlor which was rather scantily furnished, and began to speak about the attacks made upon him by party friends, and their efforts to force his withdrawal from the candidacy. The substance of what he said I can recount from a letter written at the time to an intimate friend.

He spoke as if he felt a pressing need to ease his heart by a giving voice to the sorrowful thoughts distressing him. He would not complain of the fearful burden of care and responsibility put upon his shoulders. Nobody knew the weight of that burden save himself. But was it necessary, was it generous, was it right, to impeach even the rectitude of his motives? ‘They urge me with almost violent language,’ he said, ‘to withdraw from the contest, although I have been unanimously nominated, in order to make room for a better man. I wish I could. Perhaps some other man might do this business better than I. That is possible. I do not deny it. But I am here, and that better man is not here. And if I should step aside to make room for him, it is not at all sure – perhaps not even probable – that he would get here. It is much more likely that the factions opposed to me would fall to fighting among themselves, and that those who want me to make room for a better man would get a man whom most of them would not want in at all. My withdrawal, therefore, might, and probably would, bring on a confusion worse confounded. God knows, I have at least tried very hard to my duty – to do right to everybody and wrong to nobody. And now to have it said by men who have been my friends and who ought to know me better, that I have been seduced by what they call the lust of power, and that I have been doing this and that unscrupulous thing hurtful to the common cause, only to keep myself in office! Have they thought of that common cause when trying to break me down? I hope they have.’

So he went on, as if speaking to himself, now pausing for a second, then uttering a sentence or two with vehement emphasis. Meanwhile the dusk of evening had set in, and when the room was lighted I thought I saw his sad eyes moist and his rugged features working strangely, as if under a strong and painful emotion. At last he stopped, as if waiting for me to saying something, and deeply touched as I was, I only expressed as well as I could, my confident assurance that the people, undisturbed by the bickerings of his critics, believed in him and would faithfully stand by him. The conversation, then turning upon things to be done, became more cheerful, and in the course of the evening he explained to me various acts of the administration which in the campaign might be questioned and call for defense. As to his differences with members of Congress concerning reconstruction, he laid particular stress upon the fact that, looked at from a constitutional standpoint, the Executive could do many things by virtue of the war power, which Congress could not do in the way of ordinary legislation. When I took my leave that night he was in a calm mood, indulged himself in a few humorous remarks, shook my hand heartily, and said: ‘Well, things might look better, and they might look worse. Go in, and let us all do the best we can.’6

In early 1865, Schurz had trouble getting a new command. When Mrs. Lincoln returned from the Richmond front in early April 1865, Schurz accompanied her and later wrote his wife about the trip: “The first lady was overwhelmingly charming to me; she chided me for not visiting her, overpowered me with invitations, and finally had me driven to my hotel in her own state carriage. I learned more state secrets in a few hours than I could otherwise in a year.”7

Schurz had a considerable ego. He once claimed: “I have done more than all the others to keep Lincoln on the right track.”8

Schurz had been a Wisconsin Republican leader and leader of German Americans who headed Republican efforts to attract immigrant voters in 1860. He first met Mr. Lincoln while campaigning for Republicans in Illinois in 1858. Schurz fled Germany to the U.S. in 1852 as a result of his role in 1848 Revolution — which made him unacceptable as an American diplomat to most European countries.

Schurz later served as Washington correspondent for New York Tribune, an editor for the New York Evening Post and Harper’s Weekly, Senator from Missouri (Republican, 1869-75) and Secretary of the Interior (1877-81). He sided with Liberal Republicans in 1872 and with Democrat Grover Cleveland in 1884. He was a reformer in many areas who favored civil service reform and equal rights for freed slaves.

Footnotes

- Harry. J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, pp. 82-83.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 91.(ew York Daily News, March 28, 1861).

- Carman and Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 84.

- Carl Schurz, The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, Volume II, pp. 307-308.

- Schurz, The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, Volume II, pp. 395-96.

- Schurz, The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, Volume III, pp. 103-105.

- Joseph Shafer, editor, Intimate letters of Carl Schurz, pp. 326-327.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 92.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

William H. Seward

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Cassius M. Clay

Biography (Link 2)

Abraham Lincoln and Wisconsin

Carl Schurz (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Gustave P. Koerner (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)