David Hunter was the Union Army General who issued an order freeing slaves in Georgia, South Carolina and Florida in 1862, which President Lincoln countermanded. A Whig turned Democrat and a one-time Chicago businessman, he was a professional soldier before the Civil War but because he served as a paymaster, lacked real military experience.

Hunter had the good sense to seize political opportunities and take advantage of political connections. As Army major in Kansas, he became concerned with President-elect Lincoln’s safety and volunteered to be one of his escorts on trip to Washington, D.C. in 1861. Four years later, as an army general, he oversaw President Lincoln’s funeral and escorted President Lincoln’s body back to Springfield. Later, he presided at trial of those charged with conspiring to murder the President.

His actual military career was undistinguished. Upon arrival in Washington in 1861, he sought to command the city’s defenses; instead, he was briefly appointed to take charge of the security of the White House. He worked with Cassius Clay and Kansas Senator James H. Lane to organize volunteer militia companies to protect the Executive mansion. For a few days, they bedded down in the White House East Room.

Hunter’s rapid advancement in rank was aided by Illinois Congressman Isaac Arnold, who served with Hunter at the First Battle of Bull Run. Hunter’s ambition was greater than his ability; Mr. Lincoln often had to use considerable tact to get his cooperation. When in September 1861, President Lincoln ordered Hunter to St. Louis, he used the great diplomacy: “Gen. Fremont needs assistance which it is difficult to give him. He is losing the confidence of men near him, whose support any man in his position must have to be successful. His cardinal mistake is that he isolates himself, & allows nobody to see him; and by which he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with. he needs to have, by his side, a man of large experience. Will you not, for me, take that place? Your rank is one grade too high to be ordered to it; but will you not serve the country, and oblige me, by taking it voluntarily?”1

Hunter was briefly put in charge of Fremont’s command. He was later disgruntled when he was ordered to command the Army of the West centered on Kansas. In that position, he had to work with Senator Lane to recruit Indian troops to fight for the Union. As often happened with military peers and subordinates, he quarreled with Lane.

Later, as Commander of the Department of the South operating on the Carolinas coast, he issued his own emancipation edict on April 13, 1862, which was rescinded by President Lincoln. That reversal may have influenced an opinion Hunter expressed in early October 1862 at Salmon P. Chase’s home that President Lincoln was a “man irresolute but of honest intentions – born a poor white in a Slave State, and, of course, among aristocrats – kind in spirit and not envious, but anxious for approval, especially of those to whom he has been accustomed to look up [to] – hence solicitous of support of the Slaveholders in the Border States…”2

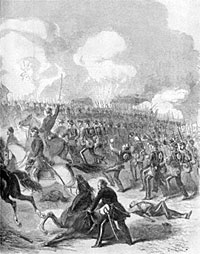

Hunter’s ideas on public and military policy were often more fanciful than practical, but his role in burning the Shenandoah Valley earned him a reputation for viciousness and hatred from Southerners. His ineptness in command – leaving the way clear for Gen. Jubal Early to attack Washington in July 1864 – led to his replacement by the more aggressive General Philip Sheridan. Historian Edward G. Longacre wrote: “Lincolns and Stanton’s panic over the [Early] raid drove Grant to make a major decision. After visiting the president at Fort Monroe on July 31, the commanding general went to Frederick, Maryland to confer with David Hunter. He came away from the meetings convinced that a more enterprising and energetic officer than Hunter should command the Army of West Virginia and other troops as well.”3

Hunter was essentially unemployed for the rest of the war – relegated to conducting courts martial.

Footnotes

- Roy M. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 513.

- David Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet, p. 172.

- Edward G. Longacre, Lincoln’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac, 1861, p. 299.

Visit

Isaac Arnold

Salmon P. Chase

Philip Sheridan

Salmon Chase’s Home

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

David Hunter and the Department of the South (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief