Union Army General George Meade commanded the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Gettysburg two days after he assumed command. Because Meade was a Pennsylvanian, President Lincoln thought he would “fight well on his own dunghill.”

Meade is generally viewed as humorous crank, but he was not insensitive to his own advancement. Less than three months before his elevation to command of the Army of the Potomac, Meade wrote his wife: “Since our review, I have attended the other reviews and have been making myself (or at least trying to do so) very agreeable to Mrs. Lincoln, who seems an amiable sort of personage. In view also of the vacant brigadier-ship in the regular army, I have ventured to tell the President one or two stories, and I think I have made decided progress in his affections.”1

Although Meade field-marshaled the Union victory at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1-3, he was criticized severely after he failed subsequently vigorously to pursue the defeated Confederate Army. Meade said the army had driven “from our soil every vestige of the presence of the invader” – leading Mr. Lincoln to exclaim: “Drive the invaders from our soil! My God! Is that all?”2 President Lincoln ordered General Meade, as Robert Todd Lincoln later recalled the order: “You will follow up and attack General [Robert E.] Lee as soon as possible before he can cross the river. If you fail, this dispatch will clear you from all responsibility and if you succeed you may destroy it.”3

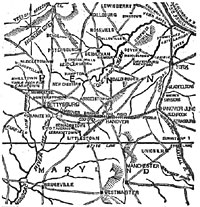

Mr. Lincoln was clearly overwrought at the failure of the Union army to overtake and destroy Confederates retreating from Gettysburg. He walked “up and down the floor [at the telegraph office in the War Department], his face grave and anxious, wringing his hands and showing every sign of distress. As the telegrams would come in he traced the positions of the two armies on the map…”4 Historian Gabor Boritt suggests that President Lincoln sent Vice President Hamlin to convey his concerns directly to Meade.

General Henry W. Halleck, who was then Union general-in-chief, wrote Meade: “You are strong enough to attack and defeat the enemy before he can effect a crossing. Act upon your own judgment and make your generals execute your order. Call no council of war.”5 Meade never caught up with Lee in time to prevent him from recrossing the Potomac. Mr. Lincoln was completely distraught at a cabinet meeting on July 14. “‘And that, my God, is the last of this Army of the Potomac! There is bad faith somewhere. Meade has been pressed and urged, but only one of his generals was for an immediate attack, was ready to pounce on Lee; the rest held back.”6 Lincoln complained to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles as they walked across the lawn from the White House: “Our Army held the war in the hollow of their hand & they would not close it.”7

Civil War scholar Eric J. Wittenberg wrote: “Lincoln and Meade did not know each other. Unlike his predecessors in army command, the general and the commander in chief had no personal relationship. This made effective communications all the more difficult. The fact that nearly all of their communications were either by telegraph or letter left room for misinterpretation and misconstruction, and that only made a difficult situation worse.”8 President Lincoln wrote a critical letter to Meade which he never sent in which he said: “I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war.”9 The President’s concerns were submitted instead through General Henry Halleck; Meade responded by submitting his resignation, which was rejected. Meade, according to historian Fletcher Pratt “was an able tactician, as witness the fact that every time he clashed with Lee, he had the better of it. But he lacked offensive spirit and, above all, any power of improvisation; demanded engineering certainties, which are usually unobtainable in war; kept saying he had not wished for the command and would be content to quit it.”10

In 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant took overall charge of the Union army but the irritable and cantankerous Meade remained in command of the Army of the Potomac under him. Meade fought ably in Antietam, Fredricksburg, Chancellorsville. Meade had served in the Army twice before the Civil War and after the war continued as a military commander in Atlanta during Reconstruction.

Footnotes

- George Gordon Meade, Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, p. 364 (April 11, 1863)

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 166.

- Gabor Boritt, editor, Lincoln’s Generals, pp. 98-99.

- Boritt, Lincoln’s Generals, p. 98.

- Boritt, Lincoln’s Generals, pp. 102-103.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 369-371.

- Eric J. Wittenberg, “An Inauspicious Beginning: George G. Meade and Abraham Lincoln in the Wake of the Battle of Gettysburg,” For the People: A Newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Summer 2008, p. 3.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, pp. 88-89.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, pp. 327-328.

- Fletcher Pratt, Stanton: Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 336.

Visit

Ulysses S. Grant

Henry Halleck

Herman Haupt

Ambrose Burnside

Daniel Sickles

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg (Link 2)

Gettysburg National Military Park

Report of Major General George G. Meade

Ulysses S. Grant (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief