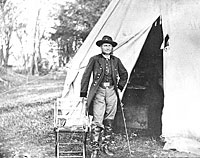

“Kill.” A Union cavalry officer more noted for his daring and rashness than his competence or good sense. In early February 1864, he passed on a plan to raid Richmond to Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan. Howard apparently told President Lincoln of the plan and the President summoned Kilpatrick to Washington for a briefing on February 12, 1864. Kilpatrick’s wife and baby son had died in the previous three months and he was desperate for diversionary action and military advancement. He quarreled with many of his superiors but maintained good political connections.

Kilpatrick biographer Samuel J. Martin wrote that Kilpatrick’s defects as a soldier appeared early in the Civil War: “he reacted rashly under pressure, striking out blindly against adversaries…without thinking of the possible consequences. He was not a man that one would want to follow into battle.”1 He took credit for himself where none was due, stole it from others who deserved it, and shifted blame for his mistakes whenever. He womanized whenever possible; his own lack of discipline carried over to his soldiers who were encouraged to burn, loot and steal from Southerners. His conduct was honorable neither with women friends or civilian enemies. His soldiers often paid for his impulsiveness with their lives and superiors sometimes confused that impulsiveness with real courage.

Historian Edward Longacre wrote: “There were many ambitious men in the ranks of the Union armies, but few lusted after success and glory with the singlemindedness of Judson Kilpatrick. Midway through the Civil War, possessed of a military career that had won him the rank of brigadier general of volunteers at age twenty-seven, Kilpatrick set specific goals for himself and determined to prosecute the remainder of the conflict in a manner that would assure their attainment. He determined, first, to become governor of his native state, New Jersey, and eventually President of the United States.”2 Longacre wrote that Kilpatrick’s “erratic habits, especially those which seemed to indicate that he was liable to lose his head when beset by self-invited peril, prompted many of Kilpatrick’s own soldiers to endorse one staff officer’s opinion that he was ‘a froth braggart without brains.’”3

According to Martin on February 11,1964 “after learning of Kilpatrick’s plans to free the Yankee prisoners held in Richmond (probably from Senator [Jacob] Howard), Lincoln sent a wire to [General Alfred] Pleasonton. ‘Order General Kilpatrick to proceed to Washington,’ he wrote, ‘and report to the President…it is not expected that [he] will be absent more than two or three days.'”4

According to historian Duane Schultz, Mr. “Lincoln greeted Kilpatrick warmly. Although the president had heard the more sordid stories about Kilpatrick, he also knew of the general’s courage in battle. If there was anything Lincoln appreciated—and longed for—among his generals, it was audacity and bravery, and Kilpatrick had more than his share of both. The two men spoke only a short time; no record remains of their conversation. The president articulated his hope for freeing the Union prisoners, and Kilpatrick expressed his confidence that he could carry it off. Lincoln also wanted his amnesty proclamation widely distributed in the Richmond area, hoping it would induce large numbers of Confederate soldiers to lay down their arms and return to the Union. Generously, it offered complete amnesty to all but the highest officials, if the would swear an oath to the United States.”5

Martin maintains that President Lincoln was probably more interest in the potential for Kilpatrick distributing leaflets on the amnesty proclamation [than in releasing federal prisoners]…Kilpatrick (with no doubt false enthusiasm) informed the chief executive that this was not only possible but also a superb plan. Lincoln was so pleased with this answer that he immediately approved the raid and sent Kilpatrick next door to the War Department to provide Stanton with details.”6 Top Union officials allowed the plan to proceed although they thought it foolish. General George Meade in particular disliked Kilpatrick and was not disturbed to see his mission fail.

In the end, the Richmond raid was bungled by Kilpatrick’s timidity and cowardice despite the numerical superiority he enjoyed. Kilpatrick’s subordinate, Ulric Dahlgren, a brave army colonel whose father was a top admiral, and many other Union cavalrymen were killed. Longacre wrote: “Dahlgren had been defeated by fewer than three hundred members of the local defense battalion. About all the raiders had accomplished was the destruction of miscellaneous railroad and private property, plus the distribution of hundreds of copies of Lincoln’s amnesty policy to Virginians who, recalling the barbarity of Kilpatrick’s raid, would now think twice about accepting Mr. Lincoln’s offer of brotherhood.” Longacre concluded: “Bad weather had played a significant role in the raiders’ failure, as had ill fortune, dramatically exemplified by the capture of messengers riding from Dahlgren to Kilpatrick. But flaws in Kilpatrick’s character had also spelled disaster for the expedition. He had fallen back with success nearly in his grasp, plagued by self-doubt and indecision on the threshold of Richmond.”8

The Confederate government maintained that orders supposedly found on Ulric Dahlgren’s body indicated that the purpose of the raid included the murder of the Confederate president and cabinet. The affair may have an unfortunate side effect: “The concept of assassination had been introduced. Kilpatrick had failed, but in time another more daring would succeed. Perhaps John Wilkes Booth was inspired by ‘The Dahlgren Papers’ and the Richmond Raid,” wrote biographer Martin.8

Kilpatrick was transferred to serve under General William T. Sherman in Georgia, South and North Carolina through the end of the war. He subsequently lectured and served two terms as U.S. ambassador to Chile, where he died.

Footnotes

- Samuel J. Martin, Kill-Cavalry, p. 37.

- Edward G. Longacre, Mounted Raids of the Civil War, p. 225.

- Longacre, Mounted Raids of the Civil War, pp. 227-228.

- Martin, Kill-Cavalry, p. 148.

- Duane Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, p. 77.

- Martin, Kill-Cavalry ,p. 149.

- Longacre, Mounted Raids of the Civil War, p. 256.

- Martin, Kill-Cavalry, p. 172.

Visit

John Dahlgren

William T. Sherman

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)