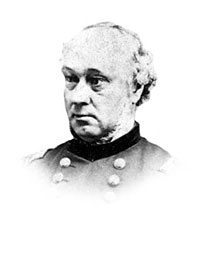

Henry W. Halleck, “Old Brains,” was the Union Army General who commanded the Department of Missouri (succeeding John C. Frémont) before his appointment as General in Chief in July 1862. Halleck was a military theoretician who was a good administrator, a bad field commander and an ineffective strategist—which he demonstrated by his collapse before and after the Second Battle of Bull Run. Halleck and President Lincoln met with General George McClellan in Halleck’s office in early September 1862 to have McClellan take charge of Washington’s defense; McClellan later reported to his wife that he was “mad as a March hare, & had a pretty plain talk with him & Abe.” Historian Allen Nevins wrote that “this awkward pedant, slow of speech and gait, who dressed shabbily, picked his teeth as he strolled after dinner, and scratched his elbows as he talked prosily in his office, had weaknesses of irresolution, confusion, and timidity which events shortly proved serious.”1 Halleck was widely disdained in Washington and in the field for his failure to take responsibility or give clear directives.

General Benjamin Butler’s attitude was strong but not unique: “I have since learned his character, which, as I always speak plainly, I find to be that of a lying, treacherous, hypocritical scoundrel with no moral sense.”2 President Lincoln’s attitude was kinder but still critical according to John Hay’s diary: “When it was proposed to station Halleck here in general command, he insisted, to use his own language, on the appt of a General-in-Chief who shd be held responsible for results. We appointed him & all went well enough until after Pope’s defeat, when he broke down—nerve and pluck all gone—and has ever since evaded all possible responsibility—little more since that than a first-rate clerk.”3

Journalist Noah Brooks noted that President Lincoln “liked to ‘talk strategy’ with Halleck, but was never very much under the general’s influence even in military matters. He had opinions of his own, and was often impatient with Halleck’s slowness and extreme caution.”4 When General Ambrose Burnside presented his strategy for the Army of the Potomac to President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, Mr. Lincoln passed it along to Halleck with a note asking him to “gather all the elements for forming a judgment of your own, and then tell General Burnside that you do approve or that you do not approve his plan. Your military skill is useless to me if you will not do this.”5 Burnside had already called for a complete change in Army leadership. Halleck submitted his resignation, saying: “I am led to believe that there is a very important difference of opinion in regard to my relations toward generals commanding armies in the field….I therefore respectfully request that I may be relieved from further duties as General-in-Chief.”6 Later that day Edwin Stanton brought Halleck’s resignation to the President shortly after he had signed the Emancipation Proclamation in his office. Mr. Lincoln wrote on his original note: “Withdrawn, because considered too harsh by General Halleck.”7

Historian Craig L. Symonds wrote that by March 1864, “Lincoln had long since concluded that for all his theoretical knowledge, Halleck simply lacked the temperament to give orders. Halleck offered innumerable suggestions but almost never issued an unequivocal order; he simply did not want to command.”8 Ulysses S. Grant replaced Halleck as General in Chief in 1864. Halleck became the army’s chief of staff—refusing to take active responsibility for most military decisions, even for the defense of Washington during Jubal Early’s July 1864 raid.

Halleck stayed in Army after war although he was scorned by General William T. Sherman for causing Sherman’s public disgrace in April 1865. Before the war, Halleck had been a successful California lawyer and businessman and author of the California State Constitution. He was also the author of a well-studied textbook on military tactics.

Footnotes

- Allen Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 12.

- Benjamin Butler, The Butler Book, p. 871.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, pp. 191-192.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 42.

- Curt Anders, Henry Halleck’s War, p. 363.

- Stephen Sears, Controversies & Commanders, p. 148.

- Anders, Henry Halleck’s War, p. 366.

- Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. 290.

Visit

The War Department

The Winder Building Annex

Edwin M. Stanton

Ulysses S. Grant

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Ambrose Burnside

Halleck Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Henry W. Halleck

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)