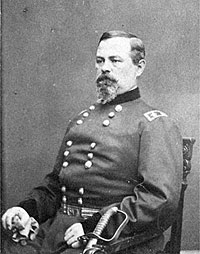

Union Army General Irvin McDowell commanded the Army of Potomac in the first Battle of Bull Run and was relieved shortly thereafter. He met with Mr. Lincoln and Cabinet officials on June 29, 1861 to discuss his plans for confronting Confederate troops near Manassas. President Lincoln was anxious for an early advance. When Winfield Scott and McDowell urged more preparation, Mr. Lincoln said: “You are green, it is true; but they are green, also; you are green alike.”1

Three weeks later, McDowell’s army engaged the Confederates and lost when Confederate reinforcements arrived to reverse early Union gains. Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “Lincoln went out of his way to console McDowell, whom he called ‘a good and loyal, though very unfortunate’ officer who had to ‘drive the locomotive as he found it. He told the general: ‘I have not lost a particle of confidence in you,’ to which the insouciant McDowell replied: ‘I don’t see why you should, Mr. President.”2

In January 1862 McDowell participated in a series of White House meetings to determine army strategy. At one session on January 10, 1862, the President told Generals McDowell and William Franklin that he was “in great distress, and as he had been to General [George B. McClellan’s] house and the General did not ask to see him, and as he must talk to somebody, he [desired] to obtain our opinion as to the possibility of soon commencing active operations wit the Army of the Potomac. If something was not soon done, the bottom would be out of the whole affair, and if General McClellan wasn’t using the army, “he would like to borrow it, provided he could see how it could be made to do something.”3 McDowell advocated another advance on Manassas — an approach that Mr. Lincoln himself preferred and McClellan opposed. Historian William Marvel argued that “McDowell so fervently wished for his own command that he would pose a threat of rivalry to any superior.”4

The still ailing McClellan showed up at a meeting on January 13, 1862 to defend his authority. The President encouraged McDowell to present the plan they had been discussing and McClellan was clearly annoyed at the preemption of his authority. “You are entitled to have any opinion you please!” said McClellan to McDowell.5 The meeting ended inconclusively with Mr. Lincoln saying: “Well, on the assurance of the General that he will press the advance in Kentucky, I will be satisfied, and will adjourn this council.”6 McDowell was subsequently appointed a corps commander under General George McClellan. McDowell was kept near Washington, D.C. during the Peninsular Campaign. That earned him the lasting enmity of McClellan, who wanted to be reinforced by McDowell as Union forces approached Richmond in June 1862.

Historian William Marvel harshly criticized the actions of both McDowell and Lincoln. Marvel wrote that “on May 16…McDowell received a War Department telegram ordering him up to Washington right away. He rode immediately to the landing and steamed up the Potomac for a late-night conference with the president, and the next day the general returned to the Rappahannock with marching orders. Lincoln had decided to build McDowell’s corps up to full strength and send him down the line of the Richmond, Fredericksbrug & Potomac Railroad toward the Confederate capital, where he would cooperate with the Army of the Potomac. Ten months after his humiliating defeat at Bull Run, McDowell would have the opportunity to redeem his reputation, and with a larger force than he had commanded in the summer of 1861. The prospect so stirred McDowell that he made no effort to keep it a secret, and within twenty-four hours the common soldiers were gossiping about it in letters home.”7 Like some other historians, Marvel concluded that withholding McDowell from McClellan crippled McClellan’s Peninsula campaign: “The fateful decision to divert half of McDowell’s troops to the Valley — which was indeed Abraham Lincoln’s decision, rather than Edwin Stanton’s – gave the Confederates at Richmond everything they had hoped for. With that single timid telegram the president threw away his best opportunity to overwhelm the Confederate capital…”8 Historian James M. McPherson, on the other hand, argued that “Lincoln was right saying that he could not afford the risk” posed by Confederates to Washington, D.C.9

McDowell served as a general in the Army of the Potomac until after the Second Battle of Bull Run when he was relieved of command at his own request on September 6, 1862. President Lincoln told Secretary of the Salmon P. Chase while visiting the Treasury Department that “the clamor against McDowell was so great that he could not lead his troops unless something was done to restore confidence; and proposed to me to suggest to him the asking for a Court of Inquiry. I told him I had already done so, and would do so again.”10 A relatively competent professional who tended to have rotten luck, he had good military sense but lack the capacity to inspire troops. After two defeats at Bull Run, he lost the trust of troops and politicians although he was subsequently cleared by a military court of inquiry of any negligence during the Second Battle of Bull Run.

In 1864, McDowell was named to command the Department of the Pacific, which effectively removed him from the combat theater. After army service, he served as a San Francisco parks commissioner.

Footnotes

- Reinhold Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 290.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 188.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 332.

- William Marvel, Lincoln’s Darkest Year: The War in 1862, p. 64.

- Shelby Foote, The Civil War, Volume I, p. 240.

- Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 311.

- Marvel, Lincoln’s Darkest Year: The War in 1862, p. 51.

- Marvel, Lincoln’s Darkest Year: The War in 1862, p. 59.

- James M. McPherson, Tried By War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief, p. 81.

- David H. Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet, p. 121.

Visit

Montgomery Meigs

Winfield Scott

George B. McClellan

John Pope

Biography

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

James S. Wadsworth

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief