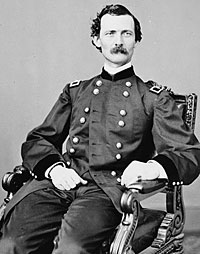

James B. Fry was a West Point graduate and artillery specialist who was served briefly in the Mexican-American War. He came to Washington in the winter of 1861 to help protect the government during President Lincoln’s inauguration. He served as chief of staff to General Irvin McDowell in the Army of the Potomac and to General Don Carlos Buell in the Army of the Cumberland before he was appointed Provost-Marshal-General on March 17, 1863 – a position that placed him in repeated contact with President Lincoln.

Fry actually came into repeated contact with the President from the beginning of the Civil War, when he commanded a light artillery unit in Washington. “Although I do not remember to have seen Lincoln until the day of his first inauguration as President, I knew him through my father. Pioneers from Kentucky to Illinois, they were friends from an early period,” wrote Fry later. “My father was an ardent personal and political friend of Douglas, and in his circle it was looked upon as presumptuous and ridiculous for Abe Lincoln to compete with the ‘Little Giant’ for the Senate of the United States.”1

Fry recalled: “During the spring of 1861 I was in charge of the appointment branch of the Adjutant-General’s Department. Upon one occasion, when I was at the White House in the course of duty, the President, after disposing of the matter in hand said: “You are in charge of the appointment office. I have here a bush-basketful of applications for offices in the army. I have tried to examine them all, but they have increased so rapidly that I have got behind and may have neglected some. I will send them all to your office. Overhaul them, lay those that require further action before the Secretary of War, and file the others.”2

Fry’s conduct impressed the White House staff. “Fry is the firmest and soundest man I meet,” wrote presidential aide John Hay in his diary. He seems to combine great honesty of purpose with accurate and industrious business habits and a lively and patriotic [solider?] spirit that is better than any thing else, today.”3

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that Fry “was recommended for his post by Grant. Taking over his duties on March 17, 1863, he showed the traits of an efficient martinet. Much the greater part of his work concerned recruiting, conscription, and desertions, but he was expected also to deal with general enemies of the government. He did this by the appointment of provost-marshals for each Congressional district, who in turn named deputy provost-marshals for the counties. The machinery thus created soon became one of the most potent arms of the government, systematic, thorough, by no means free from corruption, and widely hated. By the time the war ended Fry was as hotly controversial a figure as Holt, which is saying a great deal. But the treatment of political offenders had unquestionably been given system, and officers worked by rule, not whim.”4

The post of post marshal general gave Fry responsibility for keeping the army full of soldiers – recruiting volunteers, implementing the draft, and catching deserters. Historian Stewart Mitchell wrote that Fry “was chosen to manage both the enrollment and drafting of citizens and given the title of provost-marshal-general of the United States. One of Fry’s deputies – an assistant provost-marshal-general-was stationed in the capital of every state. New York was made an exception, three assistants being assigned to that state, one at Albany, one at New York City, and a third at Elmira.”5 Mitchell wrote: “The office of provost-marshal-general was the kind of unpopular post that some one always has to fill, but the odd aspect in the case of Fry is that he seems actually to have liked his work. Just as often as two greedy states tried to claim credit for one and the same man, this desk general would come to judgment like a Daniel. The incidental fact that his decision usually succeeded in exasperating both governors at once annoyed him not at all. Against Seymour he nursed a grudge for twenty years, and yet the record shows that Seymour’s Republican successor was no less of a ‘nuisance’ than he. It would be difficult to clear Fry of partisan feeling in this one relationship.”6

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Under the new [conscription] law the Provost-Marshal General’s office became a separate bureau in the War Department. Colonel James B. Fry correctly anticipated that about 3,000,000 men would be enrolled, but he was all too optimistic in his calculation that some 425,000 would flow into the fighting forces.”7

The nature of his duties placed Fry directly in the way of political conflicts- including the enforcement of the draft and recruitment of black soldiers Historian William Seraile wrote: “On December 10, 1863, Edward D. Townsend, assistant adjutant general, ordered James B. Fry, provost marshal general of the War Department, to instruct all War Department officers in New York to enlist suitable black candidates and send them to Rikers Island near Manhattan where the Twentieth Regiment was being organized.”8

Military scholar Geoffrey Perret wrote: “Lincoln continued to fear a backlash in pro-Union, pro-slavery states such as Maryland and Kentucky. Stanton decreed that every state must raise black regiments. An old acquaintance of Lincoln, Jeremiah T. Boyle, wrote to the Provost Marshal, Brigadier General James B. Fry, to tell him how dangerous that was. Fry was responsible for implementing the draft, but, Boyle informed him, there were fewer than seven hundred able-bodied free black males between eighteen and forty-five in the whole of Kentucky. ‘If you gain these, you will lose more than ten thousand [and] you will revolutionize the state,’ wrote Boyle.”9

The efficient Fry had little patience for political niceties. John Hay wrote in his diary in April 1864: “Fry’s nomn., [as brigadier general] which has been delayed for several days was signed today. Fry has been removing Provost Marshals without consultation & has stirred up hot water in Pennsylvania. I warned him of the trouble he was causing & he said the Secretary had authorized him to make removals where he saw fit.”10 Fry’s operating style is reflected in a diary note by one of the leaders of the U.S. Sanitary Commission later in the year. George Templeton Strong wrote: “[Henry] Bellows and [Cornelius R.] Agnew were summoned to City Point by telegram from Fry that arrived yesterday. It was obscure and alarming: ‘Grave charges against officers of the Commission demanding immediate investigation.’ We concluded that some of our people had been getting the Commission into a scrape with the military authorities; so Bellows and Agnew posted off this morning most enthusiastically, and today comes a letter from Fry, more plain-spoken than his telegram, and indicating that he charges McDonald inspector at City Point, with drunkenness and immorality. I don’t believe a word of it.”11

“Once when I went into his office at the White House, I found a private soldier making a complaint to him. It was a summer afternoon. Lincoln looked tired and careworn; but he was listening as patiently as he could to the grievances of the obscure member of the military force known as ‘Scott’s nine hundred,’ then stationed in Washington,” Provost-General James B. Fry later recalled. “When I approached Lincoln’s desk I heard him say:

“Well, my man, that may all be so, but you must go to your officers about it.”

The man, however, presuming upon Lincoln’s good-nature, and determined to make the most of his opportunity, persisted in re-telling his troubles and pleading for the President’s interference. After listening to the same story two or three times as he gazed wearily through the South window of his office upon the broad Potomac in the distance, Lincoln turned upon the man, and said in a peremptory tone that ended the interview:

“Now, my man, go away, go away! I cannot meddle in your case. I could as easily bail out the Potomac River with a teaspoon as attend to all the details of the army.”12

General Fry played a personal role in President Lincoln’s leadership of the Union’s armed forces, according to an October 1, 1864 report to the New York Herald: “This morning, John S. Staples, President Lincoln’s representative recruit, was arrayed in the uniform of the United States army, and accompanied by Provost Marshall General James Fry, N.D. Larner of the Third Ward, and his father, was taken to the Executive Mansion, where he was received by President Lincoln….Mr. Lincoln shook hands with Staples, remarked that he was a good-looking, stout and healthy-appearing man, and believed he would do his duty. He asked Staples if he had been mustered in, and he replied that he had. Mr. Larner then presented the President with a framed official notice of the fact that he had put in a representative recruit, and the President again shook hands with Staples, expressed the hope that he would be one of the fortunate ones, and the visiting party then retired.”13

Only the day before, President Lincoln had asked General Fry to discover “as nearly a perfect man physically and morally” as possible to act as his substitute in the army. Through the Ward Draft Club, Pennsylvania-born Staples was recruited and enrolled – although he never saw armed conflict .14

Fry had a more difficult task when it came to enforcing the draft in New York City in the wake of riots in mid-July 1863. Newspapers in New York published Provost Marshal Fry’s order on Saturday, July 19: “Provost Marshals will be sustained by the military forces of the country in enforcing the draft, in accordance with the laws of the United States, and will proceed to execute the orders heretofore given for the draft as rapidly as shall be practicable by aid of the military forces ordered to co-operate with and protect them.”15

John Hay noted in his diary: “The preparations for the draft still continue in New York. [General John] Dix is getting ready rather slowly. Fry goes to N.Y. tonight, armed with various powers. He carries a paper to be used in certain contingencies calling the militia of the State into the service of the General government, and calling upon rioters to disperse…”16 Fry’s role placed him in direct conflict with Governor Seymour, who complained repeatedly to President Lincoln about the draft. Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “Lincoln enrolled Fry in the epistolary battle. The provost-marshal-general denied that his officers had been guilty of partisanship, and he contended that Seymour had been given ample notice of the draft, and that the War Department had given New York credit for more soldiers than the state claimed. But Seymour was ready with more figures proving partisanship: nine Democratic districts had been assigned a total quota as large as nineteen Republican districts! It was part of a ‘manifest design to reduce the Democratic majority.”17

Although Fry was tough, he was not unreasonable about his operations. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote: “On this same day of March 11 the man-hunter Colonel La Fayette C. Baker at New York telegraphed Provost Marshal General Fry of the day before raiding bounty-jumpers and ‘capturing 590 of the most desperate villains unhung.’ Baker wanted to parade these prisoners down Broadway in irons, ‘in order that the people may have a sight of them.’ Fry’s first telegram to Baker that day said there would be no objection. Fry’s second telegram to Baker said representations held that Baker was arresting men without sufficient evidence and hereafter he must forward his evidence to Washington and have the arrests ordered from there. Personal liberty in measure was beginning to return. The hand and tone of the President were having effect. The third telegram of Fry that day Baker found abrupt and peremptory: ‘Do not march down Broadway, and do not iron them or any other men.'”18

Fry’s handling of New York quotas continue to annoy New York politicians in late 1864. Republicans in the State Senate petitioned President Lincoln in January 1865 to remove Fry: “The mistakes and blunders of this officer are doing more to weaken the friends of the administration and embarrass their efforts to sustain the war, than all other causes combined.”19 Fry recalled that the President sustained him with humor – responding to complaints from one Northern governor:

Never mind, never mind; those dispatches don’t mean anything. Just go right ahead. The Governor is like a boy I saw once at a launching. When everything was ready they picked out a boy and sent him under the ship to knock away the trigger and let her go. At the critical moment everything depended on the boy. He had to do the job well by a direct vigorous blow, and then lie flat and keep still while the ship slid over him. The boy did everything right, but he yelled as if he was being murdered from the time he got under the keel until he got out. I thought the hide was all scraped off his back; but he wasn’t hurt at all. The master of the yard told me that this boy was always chosen for that job, that he did his work well, that he never had been hurt, but the always squealed in that way. That’s just the way with Governor ____. Make up your minds that he is not hurt, and that he is doing the work right, and pay no attention to his squealing. He only wants to make you understand how hard his task is, and that he is on hand performing it.”20

Fry observed: “Time proved that the President’s estimate of the Governor was correct.”21 Fry wrote that President “Lincoln – a good listener – was not a good conversationalist. When he talked, he told a story or argued a case. But it should be remembered that during the entire four years of his Presidency, from the spring of 1861 until his death in April, 1865, civil war prevailed. It bore heaviest upon him, and his mind was bent daily, hourly even, upon the weighty matters of his high office; so that, as he might have expressed it, he was either lifting with all his might at the butt-end of the log, or sitting upon it whittling, for rest and recreation.”22

President Lincoln was not deaf to complaints and knew how to deflect them. He appointed a board to examine the fairness of state draft quotas. In February 1865, Fry wrote President Lincoln: “When you signed the order constituting a Board for the examination of the quotas, you directed me to notify you of the time it would meet. In accordance with that order, I have the honor to inform you that the Hon James Speed, Attorney General, has notified me that the first meeting of the Board will be held at 3 O’clock this afternoon”23

Fry had ample opportunity to observe the relationship between President and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. He wrote: “Lincoln, so far as I could discover, was in every respect the actual head of the administration, and whenever he chose to do so he controlled Stanton as well as all the other Cabinet ministers.”24 Fry recalled that Stanton told him “that he had never felt so sensible of his deep affection for Lincoln as he did during their final interview. At last they could see the end of bloody fratricidal war….As they exchanged congratulations, Lincoln, from his greater height, dropped his long arm upon Stanton’s shoulders, and a hearty embrace terminated their rejoicings over the close of the mighty struggle.”25

Fry concluded: “Lincoln was as nearly master of himself as it is possible for a man clothed with great authority and engaged in the affairs of public life to become. He had no bad habits, and if he was not wholly free from the passions of human nature, it is quite certain that passion but rarely if ever governed his action. If he deviated from the straight course of justice, it was usually from indulgence for the minor faults or weaknesses of his fellow-men.”26

After the Civil War, Fry continued his military career until 1881, when he turned his talents to writing books about the army, including New York and the Conscription of 1863.

Footnotes

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 387 (James B. Fry).

- AlRice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 389 (James B. Fry).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 5 (April 21, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 397.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 311.

- Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 341.

- Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 463-464.

- William Seraile, New York’s Black Regiments During the Civil War, p. 25.

- Geoffrey Perret, Lincoln’s War: The Untold Story of America’s Greatest President as Commander in Chief, p. 296-297.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger,Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 193 (April 30, 1864).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 530 (December 17, 1864).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 392-393 (James B. Fry).

- Allen D. Spiegel “John Summerfield Staples bore the president’s musket in the Civil War,” America’s Civil War, November 1991, p. 16.

- Spiegel “John Summerfield Staples bore the president’s musket in the Civil War,” America’s Civil War, November 1991, p. 16.

- James McCague, The Second Rebellion: The Story of the New York City Draft Riots of 1863, p. 175.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger,Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 74 (August 14, 1863).

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 303.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 133.

- Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Petition from New York Senate Republicans to Abraham Lincoln, January 30, 1865).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 401-402 (James B. Fry).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 401-402 (James B. Fry).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 389 (James B. Fry).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James B. Fry to Abraham Lincoln1, February 9, 1865.

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 396 (James B. Fry).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 404 (James B. Fry).

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 390 (James B. Fry).

Visit

John A. Dix

John Hay

Irvin McDowell

Edwin M. Stanton

Horatio Seymour

New York City Draft Riots

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

James Speed