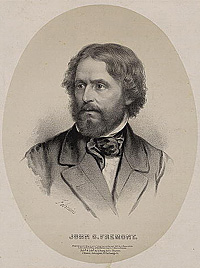

President Lincoln removed John C. Frémont, “The Pathfinder,” as Commander of Western Department in November 1861, only four months after his appointment to the position. According to Frémont biographer Allan Nevins, “Frémont “and Postmaster-General Montgomery Blair held several conferences with Lincoln upon the command to which he should be assigned; and he tells us that although the military authorities suggested eastern positions, he insisted upon the West.” Frémont later wrote: “The President had gone carefully over with me the subject of my intended campaign, and this with the single desire to find out what was best to do and how to do it. This he did in the unpretentious and kindly manner which invited suggestion, and which with him was characteristic. When I took leave of him, he accompanied me down the stairs, coming out to the steps of the portico at the White House; I asked him then, if there was anything further in the way of instruction that he wished to say to me. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘I have given you carte blanche; you must use your own judgment and do the best you can. I doubt if the States will ever come back.”1

Frémont’s wife, Jessie, was the daughter of Missouri Democratic leader Thomas Hart Benton. She was an accomplished woman who had long done much of Frémont’s writing. Jessie detailed herself to travel to Washington to petition President Lincoln on behalf of her husband. She came to the White House late on the night of September 10 with Judge Edward Coles. They waited for the President in the Red Room. “It was clear to Judge Coles as to myself that the President’s mind was made up against General Frémont and decidedly against me….in answer to his ‘Well?’ I explained that the general wished so much to have his attention to the letter sent, that I had brought it to make sure it would reach him. He answered, not to that, but to the subject his own mind was upon, that ‘It was a war for a great national idea, the Union, and that General Frémont should not have dragged the Negro into it…'”2 Mrs. Frémont told the President that:

…the General thought it would be an advantage for him if I came to explain more fully what he wished him to know for, I said ‘the general feels he is at the great disadvantage of being perhaps opposed by people in whom you have every confidence.’

‘Who do you mean?’ he said, ‘Persons of differing views?’ I answered: ‘The General’s conviction is that it will be long and dreadful work to conquer by arms alone, that there must be other consideration to get us the support of foreign countries – that he knew the English feeling for gradual emancipation and the strong wish to meet it on the part of important men in the South: that as the President knew we were on the eve of England, France and Spain recognizing the South: they were anxious for a pretext to do so; England on account of her cotton interests, and France because the Emperor dislikes us.’ The President said ‘You are quite a female politician.’

I felt the sneering tone and saw there was a foregone decision against all listening. Then the President spoke more rapidly and unrestrainedly: ‘The General ought not to have done it; he never would have done it if he had consulted Frank Blair; I sent Frank there to advise him and to keep me advised about the work the true condition of things then, and how they were going.’ The President went on almost angrily – ‘Frank never would have let him do it – the General should never have dragged the negro into the war. It is a war for a great national object and the negro has nothing to do with it.’

‘Then,’ I answered, ‘there is no use to say more, except that we were not aware that Frank Blair represented you – he did not do so openly.’

I asked when I could have the answer? ‘Maybe by to-morrow,’ said the President, ‘I have a great deal to do – to-morrow if possible, or the next day.’ To my saying, I would come for it – ‘No, I will send it to you, to-morrow or the day after.’ He asked where I was staying and was answered at Willard’s – and we came away.

As we walked through the grounds Judge Co[w]les said, in his calm way, ‘Mrs. Frémont , the General has no further part in this war. He will be deprived of all his part in the war; it is not the President alone, but there is a faction which plans the affairs of the North and they will triumph, and they are against the General. It will be like General Gates, it will be thirty years before he is known and has justice. They will give reasons for keeping him down. But they hold the power and will keep him down.’

I had to let the General know the result of the interview; I knew that to telegraph directly was impracticable; but the cipher and address I had arranged for, told him exactly what I found was the policy decided on.3

Frémont’s position had been undermined by the development of a feud between his family and the Blair family, who had been early Frémont supporters of Frémont, but became bitter enemies. Frémont was subsequently dismissed from his Missouri command.

In March 1862, President Lincoln appointed General Frémont to head the “Mountain Department” in western Virginia. Before he did so, Mr. Lincoln consulted with Henry C. Bowen, a businessman who owned the New York Independent, Lincoln biographer Alonzo Rothschild wrote:

“‘Come in,’ said Mr. Lincoln, in his unceremonious way; ‘you are the very man I want to see. I have been think a great deal late about Fremont; and I want to ask you, as an old friend of his, what is the thought about his continuing inactive.’

“‘Mr. President,’ was the reply, ‘I will say to you frankly that a large class of people feel that General Fremont has been badly treated, and nothing would give more satisfaction, both to him and to his friends, that his reappointment to a command commensurate, in some degree, with his rank and ability.’

“Do you think,’ asked Mr. Lincoln, ‘he would accept an inferior position to that he occupied in Missouri?’

“‘I have that confidence in General Fremont’s patriotism that I venture to promise for him in advance,’ was Mr. Bowen’s earnest reply.

“‘Well,’ said the President thoughtfully, ‘I have had it on my mind for some time that Fremont should be given a chance to redeem himself. The great hue and cry about him has been concerning his expenditure of the public money. I have looked into the matter a little, and I can’t see as he has done any worse or any more, in that line, than our eastern commanders. At any rate, he shall have another trial.”4

The general’s performance was again disappointing. After refusing to serve under General John Pope, he was dismissed on June 27, 1862. Pressure continued from Radical Republicans to find a command for Frémont. In March 1863, CongressmanGeorge Julian visited the President:

“On the 18th of March I called on Mr. Lincoln respecting the appointments I had recommended under the conscription law, and took occasion to refer to the failure of General Frémont to obtain a command. He said he did not know where to place him, and that it reminded him of the old man who advised his son to take a wife, to which the young man responded ‘Whose wife shall I take?’ The President proceed to point out the practical difficulties in the way by referring to a number of important commands which might suit Frémont, but which could only be reached by removals he did not wish to make. I remarked that I was very sorry if this was true, and that it was unfortunate for our cause, as I believed his restoration to duty would stir the country as no other appointment could. He said, ‘it would stir the country on one side and stir it the other way on the other. It would please Frémont’s friends, and displease the conservatives; and that is all I can see in the stirring argument.”5

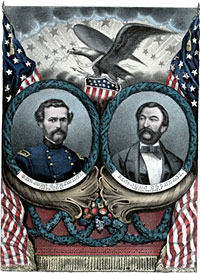

Frémont was nominated for president by a convention of radicals meting in Cleveland on May 31, 1864. When on June 1, 1864, President Lincoln learned of the nomination by 400 anti-Lincoln activists, he immediately picked up a Bible and read from I Samuel:22: ‘And everyone that was in distress, and everyone that was in debt, and everyone that was discontented gathered themselves unto him; and he became a captain over them; and there were with him about four hundred men.”6

Frémont retired as an independent candidate for President in September 1864 just before Montgomery Blair resigned from cabinet. The withdrawal was negotiated by Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler, who met with Frémont in New York. At first, the ‘Pathfinder’ had refused to commit himself, maintaining that he would have to confer with his advisors. Eventually, Frémont decided to withdraw from t he contest, but much to Chandler’s disappointment, the general had made up his mind to retire unconditionally,” according to biographer Gerald S. Hening.7 Fremont himself later wrote that Chandler’s group “brought me offers, of patronage for my friends, and of disfavor to my enemies. I refused both; my only consideration was the welfare of the Republican party.”8

Historian David E. Long wrote: “When Chandler returned to see the president on September 22, Lincoln was in a foul mood. He had received Frémont’s letter ‘and it was a document as offensive as it was tactless.’ Though he assured Lincoln that he would support the party ticket ‘in order to assure the permanence of the Union and the emancipation of the slaves,’ his attitude toward the administration had not changed. ‘I consider that this administration has been politically, militarily, and financially a failure, and that its necessary continuance is a cause of regret to the country.’ The letter was not consistent with the spirit of the agreement, but Chandler argued that there had been no stated condition as to the form of the withdrawal. Finally Lincoln relented, and on September 23 addressed a letter to Blair: ‘You have generously said to me more than once, that whenever your resignation could be a relief to me, it was at my disposal. The time has come.'”9

Frémont was the Republican candidate for President in 1856. He had become famous as an explorer in the West and for his role in the liberation of California from Mexico. According to biographer Nevins, his major faults were “his impulsiveness or rashness, and his weak judgment of men and of critical situations.”9 He served briefly as Governor of California (1847), Senator (1850-51) and later as Governor of Arizona (1878-80).

Footnotes

- Allan Nevins, Frémont, Pathmarker of the West, p. 475, p. 477.

- Nevins, Frémont, Pathmarker of the West, p. 517.

- Pamela Herr and Mary Lee Spence, editors, Letters of Jesse Frémont, pp. 264-267.

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln:, Master of Men: A Study in Character, pp. 315-316.

- George Julian, Political Recollections, pp. 229-230.

- Allan Nevins, Frémont, Pathmarker of the West, p. 475.

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 224.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume III, p. 106.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, p. 242.

- Nevins, Frémont: Pathmarker of the West, p. 618.

Visit

David Hunter

Henry Winter Davis

Zachariah Chandler

Montgomery Blair

Frank Blair

Red Room

East Room

Abraham Lincoln and Missouri

Jessie Benton Frémont

John C. Frémont and Missouri (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief