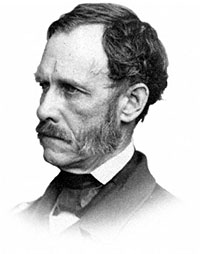

Navy ordinance expert and officer in charge of Washington Navy Yard, which President Lincoln frequently visited, John Dahlgren also invented the Dahlgren cannon. He chafed at shore duty and longed to be at sea; finally, in 1864 he was appointed to command the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. He got along better with President Lincoln than his boss, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who wrote of him in 1863: “As a bureau officer he is capable and intelligent, but he shuns and evades responsibility.”1 With the President, however, there was an immediate affinity on questions about how military ordnance could be improved.

Dahlgren was not necessarily destined for the sea duty he coveted. Historian Craig L. Symonds wrote: “Dahlgren was a slim and ‘delicate featured’ man who was exactly Lincoln’s age but looked at least a decade younger.”2 Symonds noted that Dahlgren had “a debilitating tendency to seasickness.”3

Mr. Lincoln first met Dahlgren on April 3, 1861 at a wedding party for the daughter of Dahlgren’s superior at the Navy Yard. Less than three weeks later, the superior resigned to join the Confederacy. On April 28, Dahlgren “went to the White House and pointed out to Lincoln that [Franklin] Buchanan had deserted his post and had thrown down his commission as captain. He declared that in doing Buchanan’s duty, he had earned the right to his commission. Lincoln seemed amenable to the demand but remarked that he must not go ‘across lots.’ The president was beginning to like this brash, efficient naval officer,” wrote Dahlgren’s biographer, Robert J. Schneller, Jr.4

Soon thereafter—on May 9—Mr. Lincoln visited the Navy Yard for a concert attended by the top officials in his administration. Dahlgren saw to it that Mr. Lincoln was greeted with pomp, circumstance and demonstrations of artillery. “Three days later the president dropped by the yard unexpected,” wrote Schneller. “There was no formal occasion this time; he simply wanted to visit. Dahlgren took him for a pleasant jaunt down the Potomac. On 18 May the president dropped by for another unannounced visit, this time ostensibly about ordnance business. In truth, Lincoln simply like gadgets, weapons and munitions, and these things abounded at the Washington Navy Yard.”5 When two months later, other naval officers coveted Dahlgren’s job, President Lincoln blocked their appointment, saying, “The Yard shall not be taken from [Dahlgren]…he held it when no one else would, and now he shall keep it as long as he pleases.”6

The relationship between the two men continued to be based on the President’s curiosity and interest in more effective military weapons. Dahlgren wrote his diary about a meeting with Mr. Lincoln in his office on December 22, 1862: “The President, glad to drop such troublesome business (accepting one of [Salmon Chase’s] resignations) and relaxing into his usual humor, sat down and said, ‘Well, Captain, here’s a letter about a new powder,’ which he read, and showed the sample. Said he had burned some, and there was too much residuum. ‘Now, I’ll show you.’ He got a small sheet of paper, placed on it some of the powder, ran to the fire, and with the tongs picked up a coal, which he blew, specs still on nose. It occurred to me how peaceful was his mind, so easily diverted from the great convulsion going on and a nation menaced with disruption. “The President clapped the coal to the powder, and away it went, he remarking, ‘There is too much left there.’ He handed me a small parcel of the powder to try….”7

Because Mr. Lincoln dealt directly with Dahlgren and because Dahlgren indulged the President’s fascination in weapons, Welles grew annoyed. Dahlgren pressed to be promoted and Mr. Lincoln told Welles: “I will make a Captain of Dahlgren as soon as you say there is a place.”8 When Dahlgren called on Welles in the middle of a snowstorm on February 22, 1862, Welles “told him to thank the President, who had made it a specialty; that I did not advise it.”9

Welles confided to his diary that he “cautioned [Dahlgren], as I have had occasion to do repeatedly, against encouraging the President in these well-intentioned but irregular proceedings [to contract for a new form of gunpowder]. He assures me he does restrain the President as far as respect will permit, but his ‘restraints’ are impotent, valueless. He is no check on the President, who has a propensity to engage in matters of this kind, and is liable to be constantly imposed upon by sharpers and adventurers. Finding the heads of Departments opposed to these schemes, the President goes often behind them, as in this instance; and subordinates, flattered by his notice, encourage him.1- Welles was not alone in being annoyed by Dahlgren’s self-promotion and pursuit of promotion. Dahlgren not only frequently visited the White House; he also frequently visited Washington parties where he could advance his interests. Dahlgren also entertained the President at what one naval officer called “champagne experiments” at the Naval Yard. By the end of the Civil War, Dahlgren had important enemies in Congress and the Army—as well as the Navy.

Welles was particularly exasperated in June 1863 when he learned President Lincoln had appointed Dahlgren to head a naval force to capture Charleston, South Carolina. According to Historian Robert V. Bruce, Welles “told Dahlgren bluntly that this new appointment was Lincoln’s doing, and that it would aggravate the discontent already caused by Dahlgren’s promotion to rear admiral.”11 Dahlgren had already turned down an offer to be the deputy to another naval officer. “I am ready to sign Dahlgren’s commission whenever you send it in,” Mr. Lincoln had told Welles on several occasions.12

Dahlgren was present on March 8, 1862 when news reached the White House of the Merrimac’s destruction of Union ships at Hampton Roads. President Lincoln, Welles, Edwin Stanton, William Seward met with Generals George McClellan and Montgomery Meigs. Dahlgren wrote of the meeting: “We only knew of the disasters of Saturday and deliberated on the best way of meeting the consequences, little dreaming that at the very time the Monitor was settling the question by hard knocks. The President was not in the least alarmed, but maintained his usual pleasant & suggestive mood. Generals McClellan, Meigs & myself were assigned the planning of some measures, and when I left it was with no despair of the Republic, though all of us were thoughtful enough. It was a serious business, and if the Merrimac were successful no one could anticipate the consequences to our side.13

Dahlgren lobbied persistently for a sea command and finally got his opportunity when Admiral Samuel Du Pont failed in his attempt to capture Charleston. In July 1863 Dahlgren took over command of the South Atlantic Blockading squadron. Conflicts with Union General Quincy Adams Gillmore undermined his effectiveness in that post. Pressure to replace Dahlgren was rejected by President Lincoln who said he “would be damned if he would do anything to discredit or disgrace John A. Dahlgren.” l Dahlgren was ever ambitious for rank and recognition and particularly sensitive to criticism, especially when it reached the press. However, he was consoled in early March 1864 when he had a conversation with President Lincoln at the White House. “Well, you never heard me complain,” the President told Dahlgren.14

On February 1, 1864, Mr. Lincoln was visited Admiral Dahlgren’s son, Ulric, a former naval army officer who had lost his leg in fighting after the Battle of Gettysburg. Ulric Dahlgren had been brought to his father’s home in Washington where he was visited by Mr. Lincoln before he fell into a coma. Ulric slowly recovered and returned to army service. Less than two weeks after Ulric’s visit, a Union cavalry officer, Judson Kilpatrick, also visited President Lincoln and Edwin Stanton. Kilpatrick convinced them to authorize a cavalry raid of Richmond with the intention of liberating Union prisoners held there. Ulric volunteered for the raid and was killed, on March 2, 1864, when it failed miserably. On his body were found extensive memos about the raid, including references to killing Confederate President Jefferson Davis as one of the raid’s objectives.

Historian David E. Long wrote that there were “two writings among the documents taken off Dahlgren’s body that made specific reference to the killing of Jefferson Davis and other members of the Confederate Cabinet. Because of some poor timing and lack of judgment by several people, the two writings became separated.” One documents stated: “The men must be kept together and well in hand, and once in the city, it must be destroyed and Jeff. Davis and Cabinet killed.” Another said: “Jeff. Davis and Cabinet must be killed on the spot.” Long wrote: “There was absolutely no doubt in the Confederate capital and across the South, that Abraham Lincoln had personally sponsored the attempt to kill Jefferson Davis. Within two weeks of the end of the raid, Cabinet-level officials and military leaders of the Confederacy met in Richmond and devised a plan for covert operations that would include attempts to kidnap and perhaps ultimately kill Abraham Lincoln.”.15

The stated objective of these memos was quickly disowned by Union leaders and labeled a forgery, particularly by Admiral Dahlgren. However, the authenticity of the captured documents was widely believed in the South and may have spurred discussion of similar plans—such as the one that John Wilkes Booth later employed to assassinate Mr. Lincoln. Historian Stephen Sears argued: “The idea of a raid on Richmond to release the prisoners had President Lincoln’s approval, and he certainly contemplated Jefferson Davis’s capture, but there is neither evidence nor hint that he went any further in his brief meeting with Kilpatrick. That a captured Davis might not survive among the liberated prisoners may have occurred to Lincoln, of course, but nothing suggests he would have regarded that as anything but an operational risk.”16

President Lincoln was distressed by the failure of the raid and particularly by the death of Ulric Dahlgren. According to writer Duane Schultz, “a reporter asked President Lincoln about the expedition and his part in the planning of it. Lincoln, after expressing his pleasure in Kilpatrick’s safe return and sorrow for the loss of Dahlgren, replied that he had given his consent to the raid. He added that, even though some of his generals had pronounced the scheme impracticable, he had been willing to attempt it. Releasing the prisoners had seemed worth the risk.”17

Mr. Lincoln authorized Admiral Dahlgren to try personally to arrange recovery of his son’s body. Unfortunately for Dahlgren, Union spies had dug up the body and reburied it—delaying its return to the family for over a year. The admiral spent much of that time trying to clear his son’s name.

After the Civil War, Dahlgren spent three years commanding a naval squadron off the west coast of South America before returning to Washington where he once again served as head of the Bureau of Ordnance.

Footnotes

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 341.

- Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. 138

- Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. xiii.

- Robert J. Schneller, A Quest for Glory, A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, p. 184.

- Schneller,A Quest for Glory, A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, p. 185.

- Schneller, A Quest for Glory, A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, p. 187.

- Emanuel Hertz: Abraham Lincoln: A New Portrait, p. 325.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 383-384.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 240.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 240.

- Robert V. Bruce, Lincoln and The Tools of War, p. 241.

- Schneller, A Quest for Glory, A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, p. 233.

- Bruce, Lincoln and The Tools of War, p. 173.

- Schneller, A Quest for Glory, A Biography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, p. 278.

- David E. Long, “A Time for Lincoln,” Lincoln Lore, Spring 2006, p. 8.

- Stephen Sears, Controversies & Commanders, p. 246.

- Duane Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, p. 179.

Visit

H. Judson Kilpatrick

Gideon Welles

Navy Department

Washington Navy Yard

John Dahlgren (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Samuel F. Du Pont