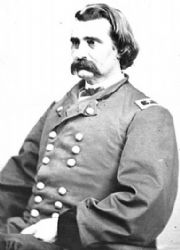

Illinois congressman (1858-1862, 1868-1871) who rallied southern Illinois for the Union and raised a regiment there. Rising to general, he served with distinction throughout the Civil War.

Congressman John A Logan so strongly supported compromise with the South in the winter of 1860-1861 that he was thought to be secessionist. His Union sentiments went unspoken until he showed up in Washington for a special session of Congress in July 1861. By then,Logan wanted to do more than speak; he wanted a military commission in the Union army. “Logan met with Abraham Lincoln at the White House,” wrote biographer Gary Ecelbarger. “The two chatted briefly about the war. Logan quickly broached the topic of raising a regiment to lead in battle. Lincoln was lukewarm about his request, suggesting that as an effective orator, he could be more effective off the battlefield by swaying enough Democrats to support the war by legislative measures. The less-than-enthusiastic response from Lincoln failed to quell Logan’s spirit.”1 President Lincoln did pledge that “authority would be given him later to raise a regiment.”2

Logan’s strong allegiance to the Union came as a surprise to friends and neighbors who knew his southern sympathies in the “Little Egypt” section of southern Illinois. As a member of Congress, he went along with a Michigan regiment to the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861 – helping fire on the enemy and care for the wounded. Historian Thomas J. Goss noted: “The Illinois congressman, dressed in civilian clothes, spent time under fire helping the wounded and rallying stragglers during the skirmishes before the main battle.”3 On August 7, 1861, Logan was named on as a regimental colonel in a brigade to be led by another Illinois Democratic congressman, John McClernand.

Logan had an immediate impact on securing the loyalty of southern Illinois to the Union. After Congress adjourned, noted General Ulysses S Grant, “Logan went to his part of the State and gave his attention to raising troops. The very men who at first made it necessary to guard the roads in southern Illinois became the defenders of the Union. Logan entered the service himself as colonel of a regiment and rapidly rose to the rank of major-general. His district, which had promised at first to give much trouble to the government, filled every call made upon it for troops, without resorting to the draft. There was no call made when there were not more volunteers than were asked for. That congressional district stands credited at the War Department to-day with furnishing more men for the army than it was called on to supply.”4 Goss wrote: “Returning to Marion, a town with divided loyalty in the heart of Little Egypt, Logan delivered a speech on August 19 that clearly and publicly stated his views on the political situation. He climbed on a wagon in the town square and expressed his support for Lincoln with inspiring rhetoric, an action that revealed his value to the administration. ‘The time has come when a man must be for or against his country,’ Logan announced, ‘I, for one, shall stand or fall with the Union and shall this day enroll for war. I want as many of you as will to come with me.’ Several immediately stepped forward, and Logan repeated his announcements until he had gathered enough men to muster into service the 31st Illinois. His political appeal was reflected by the fact that eight of the ten companies of the regiments were recruited in his congressional district, and, by some accounts, all but twelve men of his regiment were Democrats.”5 Logan resigned his congressional seat in March 1862 and was succeeded by Democrat W. J. Allen, who was arrested for his secessionist views.

Logan would become one of President Abraham Lincoln’s most successful appointments as a “political general” – far better than the controversial McClernand. Historian Thomas J. Goss wrote that “Logan would develop into one of the finest combat leaders of the war, would be a very effective field officer, and would rise to become one of William T. Sherman’s most experienced corps commanders. Like [Benjamin F.] Butler and [Nathaniel] Banks, Logan’s prewar career did little to indicate his potential as an effective general.”6 While Logan meshed with the West Point graduates who lead the western war effort, McClernand did not.

In his memoirs, Grant compared his attitude toward John A. Logan and John A. McClernand, who outranked Logan for most of the war. Grant, who helped recruit Union troops in Illinois at the beginning of the Civil War, noted that McClernand “had early taken strong grounds for the maintenance of the Union and had been praised accordingly by the Republican papers. The gentlemen who presented these two members of Congress asked me if I would have any objections to their addressing my regiment. I hesitated a little before answering. It was but a few days before the time set for the time set for mustering into the United States service such of the men as were willing to volunteer for three years or the war. I had some doubt as to the effect a speech from Logan might have; but as he was with McClernand, whose sentiments on the all-absorbing questions of the day were well known, I gave my consent. McClernand spoke first; and Logan followed in a speech which he has hardly equalled since for force and eloquence. It breathed a loyalty and devotion to the Union which inspired my men to such a point that they would have volunteered to remain in the army as long as an enemy of the country continued to bear arms against it. They entered the United States service almost to a man.”7

For the next two years, Logan made a formidable reputation on the battlefield and a controversial reputation when he returned to Illinois to support the war effort. President Lincoln himself told an aide that “John Logan was acting so splendidly now that he absolved him in his own mind for all the wrong he ever did and all he will do hereafter.”8

Logan was widely criticized by Illinois Democrats for being a traitor to their party. Few politicians or generals made such a dramatic shift in their attitude toward the abolition of slavery as did Logan. Biographer James P. Jones wrote that “Logan’s shift of position can be traced to two factors. He was no dedicated abolitionist, but by 1863 he had concluded that everything, even slavery, should be sacrificed in necessary to save the Union. He also had politics in mind. His eye on post-war politics, Logan was growing certain that a narrow Egyptian view of national affairs would not win state-wide office.”9 In one speech in July 1863, Logan addressed Illinois Democrats; “I want them to tell me how they know I am an Abolitionist….Why, I will tell you the reason. It is because we are in the Army and Abraham Lincoln is president. That is the reason. These men don’t know enough or don’t want to know that Abraham Lincoln because he is president, don’t won the Government. This war ain’t fighting for Mr. Lincoln. It is fighting for the Union, for the Government.”10

In March 1864, Logan heard rumors of his transfer from the 15th to the 17th Army corps and he telegraphed President Lincoln to object. His objections were heard and respected. Logan’s work off the battlefield also won presidential appreciation. In the fall of 1864, Logan took a leave of absence to support Mr. Lincoln’s reelection. He campaigned vigorously in southern Illinois. Logan’s work off the battlefield won presidential appreciation. In the fall of 1864, Logan took a leave of absence to support Mr. Lincoln’s reelection. He campaigned so vigorously in southern Illinois that in early October Springfield xxx Thomas J. Turner wrote the White House that General “Logan is making the most telling speeches ever made in Illinois We feel that his leave of absence must be extended till after the eighth Nov”.11 Later in the month, Congressman Elihu B. Washburne wrote President Lincoln that “Logan is carrying all before him in Egypt.”12<

In mid-November 1864, Logan wrote President Lincoln to request further military leave. Apparently, two many campaign speeches for the president’s reelection had led to a very sore throat: “I am suffering very much with inflammation in the throat am not able to do duty at present will start to my command as soon as able Can I be permitted to remain a few days for rest & improvement of health before starting.”13 Congressman Elihu B. Washburne endorsed Logan’s request in a separate letter: “Genl. Jack Logan sends word to me that he wants to go to Washington after the election to see you about certain matters that he does not wish to write about. He wishes me to obtain the permission, which I know you will most gladly grant. Please send to me such permission and I will see it reaches him.”14

Logan’s request was granted by President Lincoln on November 12: “Some days ago I forwarded to the care of Mr. Washburne, a leave for you to visit Washington, subject only to be countermanded by General Sherman. This qualification I thought was a necessary prudence for all concerned. Subject to it, you may remain at home thirty days, or come here, at your own option. If, in view of maintaining your good relations with Gen. Sherman, and of probable movements of his army, you can safely come here, I shall be very glad to see you.” Logan was allowed to come to Washington to meet personally with the President before returning to the war front.15 When Logan arrived Washington in December 1864, he was assigned the task of replacing George Thomas as head of the Army of Tennessee. But Thomas defeated the Confederate army facing him at Nashville as Logan was still en route to Tennessee, and Logan was ordered back to Washington. When he visited President Lincoln this time, Logan was given a unique task – to personally convey to General William T. Sherman the President’s thanks for the capture of Savannah. Logan later wrote of their meeting that President Lincoln “had an absolute conviction as to the ultimate outcome of the war, the final triumph of the Union army; and I well remember with what an air of complete relief…he said to me, referring to Grant – ‘We have now at the head of the armies, a man in whom all the people can have confidence.’”16

John A. Logan was born and raised in southern Illinois. As a an adult, his advocacy for the region earned him the sobriquet, “Egypt’s spokesman.” He had served in the Illinois House of Representatives in the 1850s as a Democrat and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1858. When Democrats rallied outside Springfield in support of the candidacy of Stephen A. Douglas in the summer of 1860, Logan was one of the speakers. But even at the end of the Civil War, the martyred President was not popular in southern Illinois, reported Logan’s widow in her memoirs: “Mr Lincoln was held directly responsible for the all the calamities of the war, the secessionists and their friends insisting that he caused the conflict of armies by his demand for the abolition of slavery.”17 Logan rejoined the House of Representatives in 1867 before serving two terms in the Senate (1871-1877; 1879-1886)

Footnotes

- Gary Ecelbarger, Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War, p. 82.

- James P. Jones, ‘Black Jack”: John A. Logan and the Civil War in Southern Illinois, p. 92

- Thomas J. Goss, The War within the Union High Command: Politics and Generalship During the Civil War, p. 32.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, p. 90.

- Thomas J. Goss, The War within the Union High Command: Politics and Generalship During the Civil War, p. 32-33.

- Thomas J. Goss, The War within the Union High Command: Politics and Generalship During the Civil War, p. 31.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, pp. 89-90.

- Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 212 (John Hay).

- James P. Jones, “Black Jack”: John A. Logan and the Civil War in Southern Illinois, p. 155.

- James P. Jones, “Black Jack”: John A. Logan and the Civil War in Southern Illinois, p. 181.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Thomas J. Turner to Abraham Lincoln, October 6, 1864)

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Elihu B. Washburne to Abraham Lincoln, October 27, 1864)

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John A. Logan to Abraham Lincoln, November 12, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Elihu B. Washburne to Abraham Lincoln, October 27, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John A. Logan to Abraham Lincoln, November 12, 1864).

- James P. Jones, ‘Black Jack”: John A. Logan and the Civil War in Southern Illinois, p. 243.

- Mary Logan ,Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife p. 137.

Visit