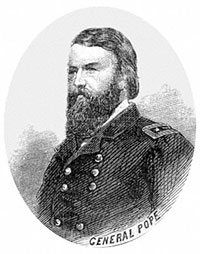

Union Army General John Pope gained a reputation in the West before President Lincoln appointed him to defend Washington, D.C. on June 26, 1862 with command of Army of Virginia—to the chagrin of generals loyal to General McClellan. As U.S. Army captain, he was one of President-elect Lincoln’s escorts on trip to Washington in February 1861. He rose through the ranks with the assistance of his Republican political sentiments, which were relatively rare in the army, and his aggressive self-promotion, which was less rare. On several occasions, Pope complained about President’s Lincoln, writing on February 14, 1862: “Mr. Lincoln’s treatment of me has been so shabby that I would feel almost humiliated today to receive an appointment from him.”1

In June 1862 Pope was called to Washington by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton—with the support of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. Both Cabinet members wanted an anti-slavery Republican to replace General George B. McClellan as head of military forces in the East. Mr. Lincoln was out of the city when Pope arrived—consulting with former General-in-Chief Winfield Scott at West Point. When President Lincoln returned, he met with Pope and Stanton and appointed Pope to command the formerly separate units operating in the Shenandoah Valley and protecting Washington. Pope later said he resisted the assignment, but the President prevailed. Pope tried repeatedly to be relieved of his new position and asked McClellan to be relieved as well. Pope was well received in Congress and the Administration but much less well received among the troops he was to command.

Pope’s arrogance was his undoing. Historian Bruce Tap noted: “On June 26 he delivered an address to the House of Representatives in which he attacked slavery and ridiculed McClellan’s estimate of rebel forces opposing him near Richmond. Then, on July 8, he was summoned before the Committee on the Conduct of the War. Although the ostensible reason for his appearance was to discuss the strategy of new command, Pope criticized McClellan at every opportunity, telling committee members that the strategy behind the Peninsula campaign was flawed. His charismatic and aggressive style impressed the committee. Wright asked if he planned to act on the defensive, merely guarding Washington. ‘I mean to attack them at all times that I can get the opportunity,’ Pope replied. By discrediting McClellan’s strategy and promising aggressive action, Pope apparently excited most committee members, who seemed unaware that his battle strategy was totally out of step with developments in weaponry, making such reckless offensive operations extremely hazardous.”3

Pope’s appointment’s importance grew when George McClellan encountered a continuing series of reverses in his Pennisular campaign. According to historian T. Harry Williams, in early July, Pope was called to a Cabinet meeting about McClellan’s problems: “Pope declared that he would do anything that Lincoln ordered, that he would move directly toward Richmond even though the enemy was between him and McClellan. One condition Pope laid down; if he marched to aid McClellan, the government was to give McClellan peremptory orders to attack the minute he heard Pope was engaged. Pope said he would have to insist on this condition because McClellan was feeble and irresolute and would let the Army of Virginia be destroyed if left to his own inclinations.”3

Ultimately, Pope presided over the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run— after which he was again succeeded by General McClellan, whose failure expeditiously to assist Pope contributed to the Union defeat. Pope was as detested by Union troops as McClellan was loved; his personality tended toward arrogance and braggadocio. The battle, however, turned out badly. John Hay recorded in his diary of September 1, 1862:

Every thing seemed to be going well and hilarious on Saturday & we went to bed expecting glad tidings at sunrise. But about Eight oclock the President came to my room as I was dressing and, calling me out, said, “Well, John, we are whipped again, I am afraid. The enemy reinforced on Pope and drove back his left wing and he has retired to Centreville where he says he will be able to hold his men. I dont like that expression. I don’t like to hear him admit that his men need holding’

After a while, however, things began to look better and people’s spirits rose as the heavens cleared. The President was in a singularly defiant tone of mind. He often repeated, “We must hurt this enemy before it gets away.” And this morning, Monday, he said to me when I made a remark in regard to the bad look of things, “No, Mr. Hay, we must whip these people now. Pope must fight them. If they are too strong for him, he can gradually retire to these fortifications. If this be not so, if we are really whipped and to be whipped, we may as well stop fighting.'”3

After the Second Battle of Bull Run, Pope went to the White House to read a report complaining about fellow generals. The Cabinet refused to allow publication of his criticisms. As a consequence, the next day Pope was transferred to command of the Army of Northwest, headquartered in Minnesota until 1865, but General Fitz John Porter was courtmartialed for failing to come to Pope’s aid during the battle. (The general continued to be abusive toward the President, writing a friend that Mr. Lincoln was “feeble, cowardly, and shameful.”5) Pope adopted a scorched earth policy against the Sioux uprising there and arrested Indians for rape and murder. President Lincoln commuted the death sentences of many convicted of those crimes.

Pope’s father, Nathaniel, was the first U.S. District Court judge for Illinois before whom Abraham Lincoln practiced.“I first saw him to know him [Lincoln] personally in Chicago in 1850,” Pope wrote in his memoirs. “Being a citizen of Illinois and having won some small reputation during the Mexican War, but recently ended, Mr. Lincoln, with some of the other lawyers, was good enough to call upon me. The general impression left on my mind was of a tall, gaunt, angular man, very homely and awkward, but with a very intelligent and kindly face.”6

In his memoirs, Pope wrote that President Lincoln “was no more a saint than Washington and I presume no more of a sinner, but, like General Washington, he had weaknesses and peculiarities of his own, which need to be much more fully set forth before we can know him as he was and as I have doubt he would prefer that his memory should be transmitted to his posterity.”7 After the Civil War, Pope fought Indians in the West until his retirement from the Army in 1886.

Footnotes

- Peter Cozzens, General John Pope: A Life for the Nation, p. 52.

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder, p. 127

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, p. 124.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, pp. 37-38.

- Cozzens, General John Pope, p. 209.

- Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Giardi, editors, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, p. 175.

- Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Giardi, editors, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, p. 175.

Visit

George B. McClellan

Henry Halleck

John Hay

Irvin McDowell

Biography

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief