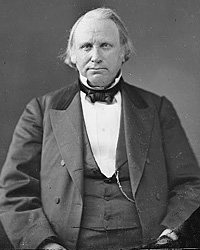

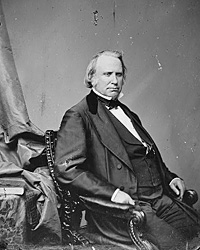

Henry Wilson, nicknamed “Natick Cobbler,” was a Senator from Massachusetts (Republican, 1854-73). Possessed of strong principles and a strong character, he chaired the 1852 national Free Soil Convention. Like fellow Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, Wilson was a strong abolitionist. He was ardent and outspoken in support of emancipation and black civil liberties – but politically in advance of both his constituents and the Lincoln Administration.

Wilson served briefly as a colonel in the Union Army under General McClellan. “He had raised a three-years’ regiment, which he had brought to Washington, but not wishing to take the field, he had resigned the command, and had solicited from General McClellan a position on his staff. When he reported for duty he was ordered to appear the next morning mounted, and accompanied by two other staff officers, in a tour of inspection around the fortifications. Unaccustomed to horsemanship, the ride of thirty miles was too much for the Senator, who kept his bed for a week, and then resigned his staff position,” wrote journalist Ben Perley Poore.1

Wilson biographer Ernest A. McKay observed: “Not content with playing a purely legislative role in the midst of wartime excitement, and yet not wanting to relinquish the power of his office, Wilson turned down a commission as Brigadier General from Abraham Lincoln, but accepted a place as a Massachusetts Colonel. For a brief time between sessions Wilson served on the staff of General McClellan. Both he and Secretary of War Stanton believed that he could obtain some knowledge of the organization and condition of the army while serving there. But his chief purpose was to encourage recruiting.”2

More importantly, he was chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs throughout the Civil War. Wilson biographer Richard H. Abbott wrote: “Henry Wilson’s duties as chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs stretched his great industry to its limits. He once admitted to his friend William Schouler that he was ‘pressed beyond endurance with work.’ The senator did not shirk his responsibilities, for he had visions of a goal far greater than that of raising and organizing troops. To him the Federal armies and the Republican party were instruments to achieve that which he had sought for thirty years, but which he had once thought could not be accomplished in his lifetime: the abolition of slavery. At first he moved against slavery carefully, for he knew that Northern opinion was not ready to countenance abolition, and the Lincoln administration desperately needed political support. After the war pushed on into its second year, however, and Lincoln seemed unwilling to do anything at all about slavery, Wilson risked a breach with the administration in order to wage his own war on the institution.” She shepherded legislation through the Senate providing emancipation for the District of Columbia – which President Lincoln signed on April 6, 18623

Pennsylvanian Alexander K. McClure wrote: “There were men of greater intellectual force with whom Wilson came in contact both in the senate and in his tireless efforts for his cause during his career, but he never met a foeman in the forum whose respect he did not win by the dignified, intelligent and chivalrous tone of his arguments. There was not the trace of the demagogue in his organization. He was of imposing presence; was always clad in elegant but unostentatious apparel, and his bright, kindly round face unmistakably proclaimed his sincerity and manliness. He was one of the gentlest of men.”4 According to contemporary Carl Schurz, Wilson’s “eloquence did not rise to a high level, but became impressive by the ingenuous force with which it portrayed his convictions. He justly enjoyed the reputation of being a thoroughly honest and well-meaning man. There was something childlike in his being, even in his political dealings, although he may have considered himself, and to a certain extent he was, a skillful political manager.”5

Wilson’s relationship with the Confederate spy, Rose O’Neal Greenhow, may have been the source of much Southern espionage information. Biographer McKay suggested that Wilson’s connection to Rose Greenhow may have been overblown. He noted all references to him in her memoirs were contemptuous and that the love letters she preserved were signed only “H.” He noted that the handwriting resembled that of Wilson’s clerk on the Military Affairs Committee, Chicago journalist Horace White.6 Wilson had less entrée to the White House than Senator Charles Sumner, but he provided more dramatic illustration of his entree when he brought New York Tribune correspondent Henry Villard to the White House in the middle of the night to bring news of the Union defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862.

According to Mark O. Hatfield, “Wilson pressed Lincoln to issue an emancipation proclamation and worried that the final product left many people still enslaved in the border states. Known as one of the most persistent newshunters in Washington, Wilson brought knowledgeable newspaper reporters straight from the battlefield to the White House to brief the president. Despite his intimacy with Lincoln, Wilson considered him too moderate and underestimated his abilities. The senator was once overhead denouncing Lincoln while sitting in the White House waiting room. He hoped Lincoln would withdraw from the Republican ticket in 1864 in favor of a more radical presidential candidate.”7 Wilson became a leader of the Chase for President boomlet in early 1864.

Nevertheless, Wilson was admirer of President Lincoln—especially his compassion. He wrote later that “I had nearly fifteen thousand nominations of his to act upon, and was often consulted by him in regard to nominations, and, also, the Legislation for the army and I have the best opportunity to see him under all circumstances.” He pronounced the President to be “loving, tender, firm and just.”8 Wilson recalled later “talking early one Sabbath morning with a wounded Irish officer who came to Washington to say that a soldier who had been sentenced to be shot in a day or two for desertion had fought bravely by his side in battle. I told [President Lincoln that we had come to ask him to pardon the poor soldier. After a few moments reflection, he said, ‘My officers tell me the good of the service demands the enforcement of the Law, but it makes my heart ache to have the poor boys shot. I will pardon him, and then you will all join in blaming me for it. You all censure me for granting pardons, and yet you all ask me to do so.”9

Wilson also recalled how President Lincoln was pressured in August 1864 to change his commitment to emancipation as a precondition to peace. It was in the middle of a political upheaval in which both radical and conservative Republicans were seeking to replace Mr. Lincoln on the Union ticket. Wilson traveled to Washington to exert a counter-pressure and argue that any weakening in support for emancipation would be a political mistake. In reply, Mr. Lincoln “spoke of the pressure upon him, of the condition of the country, of the possible action of the coming Democratic Convention and of the uncertainty of the election in tones of sadness. After discussing for a long time these matters, he said with great calmness and firmness,—’I do not know what the result may be, we may be defeated, we may fail, but we will go down with our principles. I will not modify, qualify nor retract my proclimation [sic], nor my Letter.'”10

In the September 1864, Wilson wrote President Lincoln a letter of political advice: “”We ought to carry all the States but New Jersey and Kentucky, and I hope we shall fight for all but those states and leave our friends in those states to their best alone. Missouri ought to be seen to at once. Wade ought to be in the field to brake the force as far as he can of manifesto. Chase should speak to the country for you. Winter Davis, Kennedy, and Johnson of Maryland should be brought in it possible. Dix, Rosecrans, Grant, Logan, and all the generals should be induced to come out for you. No man should be passed over nor neglected. We are to have a terrible contest. Let us not throw away any help. If we are beaten our friends will cast the blame wholly on you for they believe they can carry the country easy with another candidate. You must lose no time in the work of putting all our friends in the fight. You will think I have written you a very strange letter. I have written it as a friend of our cause and a friend of your election. Read it and then destroy it.”11

A shoemaker by trade, Wilson was a long-time member of the Massachusetts Legislature, ending his career there as President of the State Senate. He also served as editor of the Boston Post. As the Republican candidate for Governor of Massachusetts in 1854, Wilson oined the Know-Nothing movement to control it—assuring his own defeat but the election of a Republican legislature.

Wilson had been one of those Eastern Republicans in 1858 who favored the reelection of Illinois Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas. According to biographer John L. Myers, “Wilson appears to have concluded that splitting the Democrats was all important and that it could be advanced by reelecting Douglas…Wilson in 1858 believed the nomination of Lincoln was ‘a fatal mistake’ and Representative William Kellogg of Illinois that same year provided extensive evidence that Wilson had wanted Illinois Republicans to endorse Douglas.”12

Still, he was a committed opponent of slavery. Myers wrote: “Above everything – family, political gain, money – he believed in the abolition of slavery. Few politicians, especially in Massachusetts, would subject themselves to the criticism of attending meetings of Garrisonian antislavery societies. Wilson did with regularity. Wilson was also criticized by Democrats and by some of his own associates for becoming a Know Nothing…Wilson’s focus was clear; he wanted to end slavery as quickly as possible, and the means sometimes had to be adjusted to fit realities.”13

Wilson served until his death as Vice President in Ulysses S. Grant’s second administration—despite his involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal.

Footnotes

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, p. 99.

- Ernest A. McKay, Henry Wilson: Practical Radical: A Portrait of a Politician, p. 147.

- Richard H. Abbott, Cobbler in Congress: The Life of Henry Wilson, 1812-1875, p. 142.

- Alexander K. McClure, Recollections of Half a Century, p. 289.

- Carl Schurz, The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, Volume II, p. 117.

- McKay, Henry Wilson: Practical Radical: A Portrait of a Politician, p. 154.

- Mark O. Hatfield, Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789-1993, pp. 235-236.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editors, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 561.

- Wilson and Davis, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 562.

- Wilson and Davis, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 562.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from Henry Wilson to Abraham Lincoln, September 5, 1864).

- John L. Myers, Henry Wilson and the Coming of the Civil War, p. 379.

- Myers, Henry Wilson and the Coming of the Civil War, p. x.

Visit

George B. McClellan

Charles Sumner

Abraham Lincoln and Massachusetts