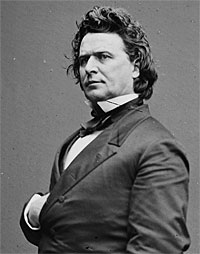

James M. Ashley was a newspaper editor, Ohio Congressman (1859-1869) and the prime sponsor of the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery. He was more radical than President Lincoln but cooperated with him to round up the House votes for the amendment’s approval in January 1865. Ashley’s presidential sentiments in 1864 were closer to his fellow Ohioan, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.

In the 1850s, Ashley had become a political ally of and strategist for Chase. Historian John Niven wrote: “Ashley’s political career had been as checkered as his business affairs. The son of a peripatetic Campbellite minister, he had been brought up in a poor, highly religious family that had moved about Illinois, the Ohio Valley, Kentucky, and Western Virginia.”1 Niven wrote: “Ashley possessed in abundance character traits that made him attractive to Chase. He had a strong commitment to temperance, a growing popular force in Ohio; he was a dedicated antislavery man; he had been a Democrat; and he was an ambitious political organizer and publicist. Briefly a Know Nothing, Ashley parted from that organization and, indicative of his impulsive temperament, had become a fierce opponent of nativism in any form.”2

Congressman Ashley was a hardliner against secession and compromises. In the December 1860 session of Congress, he voted against even the creation of the Committee of Thirty-three which was designed to seek a compromise with the South. He clashed with one of Mr. Lincoln’s Illinois representatives, William Kellogg and suggested that the pro-compromise Kellogg should be “kicked by a steam Jackass from Washington to Illinois.”3 In his adamant opposition to any compromise on slavery, Ashley fought the proposed constitutional amendment which would have prohibited the Federal government from interfering with slavery in the South. Ashley took the position that House approval required two-thirds of the membership of the House, not two-thirds of those voting. Ashley’s position was not sustained by the House Speaker – thus setting up a ruling which anti-slavery activists used four years later to pass the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

In the early days of the war, Ashley was determined that strong efforts would be needed – including emancipation – for the Union to achieve victory. According to biographer Robert F. Horowitz, Ashley “maintained that under the war powers clause of the Constitution, the government had the right to interfere with slavery in the states and to initiate complete abolition, and that the power should be used against the oligarchic slaveholders. He firmly believed that his views would eventually be accepted by the administration and the American people.”4

And he clashed with President Lincoln on reconstruction. One day after another irritating confrontation, President Lincoln said to Ashley as he was about to leave the White House: “Ashley, that was a great speech you made out in Ohio the other day.” Irritated, Ashley denied he had made any recent Ohio speech because he hadn’t left the Capital. But the President defused the situation with a joke and said: “Come again Ashley, and we will take up reconstruction again.” Several decades later, Ashley recalled: “By the gentlest of methods this great leader held together all the discordant elements in the Republican party, both in Congress and the country.”5

“Our duty as a nation,” Ashley told a Toledo gathering in late November 1861 “has seemed to me from the first so plain that I have been not a little amazed at the apparent hesitancy and want of policy on our part.”6 Ashley introduced a resolution that “proposed emancipation, the confiscation of rebel property, and the proscription of the political rights of most Confederates,” wrote historian William C. Harris. “Although many Republicans favored the radical Ashley bill, a coalition of conservative Republicans, border-state Unionists, and Democrats, with Lincoln’s support, defeated it in the House of Representatives.”7

Efforts to pass the Thirteenth Amendment in the House failed in the spring of 1864, but President Lincoln and Congressman Ashley worked together to reverse that vote after they were both reelected in November. Historian Michael Vorenberg wrote: “Because the amendment required a supermajority for adoption, Ashley wisely kept the wording as it was and used other legislation, such as his own reconstruction bill, to press for explicitly radical measures like black male suffrage and land for ex-slaves. Ashley needed harmony within his own party and cooperation between the two parties, but, early in the session, it seemed that he would get neither.”8 Republican leaders believed they lacked the votes to assure passage by mid-January so Ashley postponed a vote on the amendment.

Historian Allen Guelzo wore that “Ashley went to work, lobbying queasy Republicans and nervous Democrats, backed by Lincoln’s promise that ‘whatever Ashley had promised should be performed.'”9 Ashley biographer Robert F. Horowitz wrote: “With Lincoln’s help, Ashley had been making an all-out effort to round up needed votes.”10 But progress in the House was slow and even with the President’s help, a vote on the amendment had to be postponed twice during January 1865. According to Horowitz, “On January 24, Ashley sent out another printed circular, informing all Republican congressmen that their presence in the House on the thirty-first of January was absolutely essential,” wrote Horowitz. “It is now believed that if every administration member is present, a sufficient number of the opposition with either absent themselves or vote with us to secure its passage,” Ashley wrote his colleagues.”11

Lincoln scholar Frank J. Williams wrote: “When Democrats and other conservatives began to waver in their support of the measure because they heard that rebel peace commissioners were en route to Washington and they feared that an antislavery amendment would kill any chance for peace, James Ashley, the floor manager of the amendment, sent word to Lincoln to write a message stating that no peace commissioners were on their way. Lincoln complied, knowing full well that the rebel commissioners, though not headed to Washington, were coming to or were already present at nearby Fortress Monroe. As Robert V. Bruce has said, ‘Lincoln could split hairs as well as rails.'”12 Historian Vorenberg wrote: “With the peace rumors temporarily dispelled, Ashley tried to shore up wavering congressmen by marching out Democrats newly committed to the antislavery cause.”13

On January 31, the amendment came to a vote – but not until there were delays caused by more speeches for and against the amendment. After a narrow but conclusive 119-56 vote in favor, floor manager Ashley rejoiced with the amendment’s other supporters, black and white, in the chamber. But unlike some House supporters, he did not go to the White House; instead he went to visit Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in the nearby War Department. “Glory to God in the highest! Our country is free,” Ashley telegraphed the Toledo Commercial.

Ashley was assaulted by Republican colleagues upset by delays in the proceedings as Democratic congressmen explained changes in their upcoming votes. “But the Ohioan remained calm: he was confident of victory,” noted biographer Robert F. Horowitz. “Finally a roll call vote was taken on a motion to table the motion to reconsider. It failed, 11 nays to 57 yeas. The House now voted 112 to 57 to reconsider the action of June 15, 1864. A shudder passed over the galleries as the vote was announced: it was less than the two-thirds needed to pass the joint resolution. Ashley now refused to yield to a motion to postpone, and amid great tension a roll call on the resolution began.”14

Ashley was also one of the most active architects of reconstruction plans. “Of several reconstruction proposals offered in the opening weeks of the session, the most important was a bill introduced from the radical faction by James Ashley on December 21, 1863,” wrote historian Herman Belz. “Far from being a reaction against the executive plan of reconstruction, Ashley’s bill followed Lincoln’s proclamation in many important respects; indeed, contemporary observers saw it as implementing and filling in the outline of the presidential plan contained in the amnesty proclamation. Just as significant was a shift in Ashley’s bill from a purely territorial solution to reconstruction to a solution emphasizing the guarantee of a republican government as the basis of congressional legislation.”15

Ashley changed some important points in his original reconstruction bill submitted in 1862. Rather than adopting the original notion of state suicide. Moreover, wrote historian Belz, Ashley dropped that controversial position. “In contrast to the bill of 182, which regarded slavery as having been extinguished along with the state itself, Ashley’s bill of December 1863 regarded the prohibition of slavery as an element of republican government: ‘Slavery is incompatible with a Republican form….”16 Historian William C. Harris wrote: “When Congress convened in December, Radicals put forth a mild challenge to Lincoln’s reconstruction plan. On December 15 James M. Ashley of the House Select Committee on the Rebellious States introduced a bill ‘to guarantee to certain States whose governments have been usurped or overthrown, a republican form of government.” Historian William C. Harris contended that Lincoln supported bill. Harris wrote that “in apparent deference to Lincoln’s reservations and those of most Republicans, Ashley altered his bill by striking out the provisions of that would allow black voting and jury duty. Radicals like Henry Winter Davis, however, were dissatisfied with the watered-down version and, joined by Democrats who opposed any reconstruction requirement, particularly emancipation, forced Ashley repeatedly to revise his bill, to the point that it was unacceptable to a majority of the members. Finally, on February 21 it was tabled by an overwhelming vote in the House. Other congressional efforts to pass reconstruction legislation met a similar fate.”17

Decades after the Civil War, Ashley wrote: “By virtue of his office Abraham Lincoln became the Nation’s leader – by virtue of his abilities its savior….There was in his mental make-up a marvelous blending of sunshine and sorrow – of earnestness and apparent levity, of humor, of hopeful prophecy, but of inexorable logic; and he did his work simply, grandly and well.”18

In the House, Ashley served as chairman of the Committee on Territories. After his congressional service ended, Ashley was appointed Ashley territorial governor of Montana by President Ulysses S. Grant. He was also president of the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Northern Railroad (1877-1893).

Footnotes

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: a Biography, p. 159.

- Niven, Salmon P. Chase: a Biography, p. 159.

- Robert F. Horowitz, The Great Impeacher: A Political Biography of James M. Ashley.

- Horowitz, The Great Impeacher: A Political Biography of James M. Ashley.

- James M. Ashley, “Address of Hon. J. M. Ashley, at the fourth annual banquet of the Ohio Republican league,” New York Evening Post print [1891], p 15.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America, p. 66.

- William C. Harris, With Charity for All: Lincoln and the Restoration of the Union, p. 36.

- Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, p. 179.

- Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America, p. 251.

- Horowitz, The Great Impeacher: A Political Biography of James M. Ashley, p. 104.

- Horowitz, The Great Impeacher: A Political Biography of James M. Ashley, p. 104.

- Frank J. Williams, Judging Lincoln, p. 135.

- Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, p. 206.

- Robert F. Horowitz, The Great Impeacher: A Political Biography of James M. Ashley, p. 105.

- Herman Belz, Reconstructing the Union: Theory and Policy During the Civil War, p. 177.

- Belz, Reconstructing the Union: Theory and Policy During the Civil War, p. 179.

- Harris, With Charity for All, Lincoln and the Restoration of the Union, pp. 236-237.

- Ashley, “Abraham Lincoln: Addressed Delivered in Memorial Hall, Toledo, Ohio, February 12, 1918,” p. 5.

Visit

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Thirteenth Amendment, Passage

Biography from Impeach Andrew Johnson

Congressional Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Ohio

Abraham Lincoln and Thirteenth Amendment