New Hampshire Senator (Democrat, 1847-53, Republican, 1855-1865) John P. Hale was appointed Minister to Spain after losing re-election in 1864, serving until 1869. Hale fought persistently with Secretary of Navy Gideon Welles over naval affairs, which Senate committee he headed until his Senate defeat.

Hale was a born critic and a natural pain to any Administration in power. Biographer Richard H. Sewell wrote: “For sixteen years a leading defender of a minority faith, a political guerrillist to whom party loyalty meant little, Hale never learned the importance of team play, never understood the ways in which power is responsibly administered.”1 Presidential aide John Hay wrote in an anonymous newspaper dispatch in December 1861: “All the reputation he has ever gained in Congress has been through his ceaseless and merciless attacks upon the party in power. Given an Administration measure, you are sure to have a witty, caustic and unavailing speech from the New Hampshire Senator against it. He has been fighting so long for the rights of the down trodden minority, that he has fallen in love with the very idea of hopeless championship. And now that the minority has come into its possessions and needs his arm no longer, he turns from it in disgust and sets diligently about making a another little minority to fight for. He has made several little dashes in that direction, but he really had hardly he heart to go any noticeable lengths in his denunciations of his friends, and all the Republican sin the Senate liked Hale so well that any acrimony of debate has hitherto been avoided. His last manifestation of spleen on Thursday was most singular and only not surprising because it was his. Nothing could have been imagined more inopportune or ill-chosen.”2

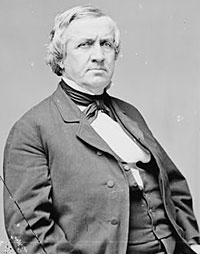

At the beginning of the Civil War, John Hay described Hale as “a well-looking elderly gentleman, tall and portly, of ruddy countenance, pleasing and intellectual features, and a particularly fine head. Notwithstanding that he sat so quietly and with such an unpretending air, with his plump hands crossed over his majestic front, I could not get rid of the impression that he was a man of mark, and was not much surprised when a mutual friend coming in designated him as ‘Senator Hale of New Hampshire.'”3 Like other Senators, Hale sought his state’s share of political jobs. Biographer Richard H. Sewell wrote: “As a jobber in the fruits of patronage, Hale was neither an outstanding success nor a bankrupt failure. Although early in the war he lost all favor with the Post Office and the Navy Department, and although his relations with Secretary of State Seward were cool, he was persona grata with the other departments and used his personal charm to advantage.”4

A major thorn in the administration of the Union’s naval policy was the continuing feud between Senator Hale and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles occasioned by Welles’ use of his brother-in-law as a purchasing agent at the beginning of the Civil War. Welles biographer Richard H. Sewell wrote: “It may be that he objected to the Secretary’s appointment from the start, that he himself coveted the office. He no doubt knew that the testy chief of the Navy Department had urged the annexation of Texas in 1845 and as a regular Democrat had willingly supported Franklin Pierce in 1852. Even after Kansas-Nebraska and his conversion to the Republican party, Welles showed none of Hale’s awareness of slavery as a moral problem. Still another reason for Hale’s growing distrust was Welles’ unwillingness to pure his department of subordinate officers who had dirtied their hands for ‘fraudulent’ Democratic administrations. ‘I felt hurt,’ Hale later recalled, ‘I felt hurt as I believe few men could be, when I saw the Secretary of the Navy retaining the same corrupt tools who had [in 1859] received the censure of the House of Representatives’ for defrauding the government. But what most set Hale against the Secretary was word that in May Welles had designated his brother-in-law, George D. Morgan, sole agent in New York to purchase vessels for the navy. At the same time, the Secretary had abandoned the established practice of sealed bidding, and had authorized Morgan to accept commissions from sellers, instead of paying him a salary out of Navy Department funds. It smacked to Hale of extravagance and nepotism.”5

Welles biographer John Niven wrote: “Shrewdly, Hale refused to judge the worth of the transactions, but concentrated his attack on the commissions. Carried away by his own rhetoric, he accused Welles of corruption, and in a final outburst on the Senate floor, he implied that the entire administration was riddled with graft and waste. Hale’s remarks made good newspaper copy. For several weeks, editorials in the newspapers and cartoons in the illustrated weeklies pilloried Welles. Conscious that any retreat on his or Morgan’s part would reflect upon his probity as well as his judgment, Welles refused to recognize that any wrong had been committed. Nor did he lack for defenders in influential quarters.”6

Sewell wrote that “there was much misunderstanding all around; the angels could have chosen neither side. Hale’s interventions on behalf of shipbuilders and naval contractors may indeed have been unsavory, but hardly more so than the actions of the President, Vice President – even Mrs. Lincoln – all of whom made ‘recommendations’ to Welles about the purchase of ships.”7

Historian Niven wrote: “Hale’s tactics were sound, his sense of timing superb. His attack was launched at Welles’ most vulnerable point – nepotism. He waited until the newspapers had thoroughly raked over the War Department disclosures before he had the Senate instruct his committee to investigate Navy contracts.” Niven wrote: “The newspaper campaign against Welles, which had never really ceased, picked up momentum after it was learned that Hale would investigate the Navy Department. On January 11, 1862, the day Lincoln accepted Cameron’s resignation, the Senate directed Welles to make a full report on Morgan purchases. Anticipating its action, he had been shaping his defense for a month. He was ready with a complete report on all the Morgan transactions.”8 Welles’ report was generally persuasive – except to Hale who replied with a report of his own on January 27 attacking the size of Morgan’s commissions. Hale charged “that the liberties of this country are in greater danger to-day from the corruptions and from the profligacy practiced n the various Departments of this Government than they are from the open enemy in the field.”9

According to historian John Niven, “The Department’s defenders helped with favorable publicity, but the timely victory of Flag Officer [Andrew H.] Foote in capturing Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, helped more. News of this brilliant exploit, again an all-Navy affair, blunted Hale’s onslaught. More important to Welles’ continued tenure was the attitude of the President. Lincoln knew that the Navy Department was not the sleepy place the newspapers pictured it. From the onset of hostilities Welles, and then Welles and Fox in a team arrangement, had displayed remarkable energy and foresight.”10

Attorney General Bates recorded his observations in his diary early in the month: “There is a feverish excitement in both Houses: In the senate there were strong indications of opposition to the adm[inistrato]n. And Mr. Hale led off very plainly in that direction, but recoiled, as to oppose the adm[istratio]n. now is to oppose the War and the nation. But as the steam is up, it must find a vent, and so is let off against individuals – [former War Secretary Simon] Cameron is driven out, and exiled to Russia, and now they are battering away upon Welles, and many think that he must yield to the storm. I will not decide that injustice was done to Cameron – I do not judge his case. But I think that Welles gets hard measure for his faults. He is not strong or quick, but I believe him an honest and faithful man.”11

In early January 1863, Senator Orville H. Browning made one of his frequent calls at the White House: “Found Senator Hale at the Presidents. Before he left the President said having two Senators present he wished to make a speech to us. He then took us to a map and pointed out the relative positions of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio. He said since the proclamation the negroes were stampeding in Missouri, which was producing great dissatisfaction among our friends there, and that the democratic legislatures of Illinois & Indiana seemed bent upon mischief, and the party in those states was talking of a union with the lower Mississippi states. That we could at once stop that trouble by passing a law immediately appropriating $25,000,00 to pay for the slaves in Missouri – that Missouri being a free state the others would give up their scheme – that Missouri was an empire of herself – could sustain a population equal to half the population of the United States, and pay the interest on all of our debt, and we ought to drive a stake there immediately – He said to Hale you and I must die but it will be enough for us to have done in our if we make Missouri free.”12

Hale’s vendetta against the Navy Department continued. Biographer Richard H. Sewell wrote that Hale “spent his waking hours sniffing out corruption (real and imaginary) in the navy’s several branches and bureaus; bickering with Welles over the appointment of midshipmen, the removal of a clerk, or the enlargement of the Portsmouth Navy Yard; complaining to all who would listen of the incompetence and venality of the Secretary’s principal advisers.”13 By August of 1863, Hale’s character had alienated even an admirer like Hay. After describing President (“The Tycoon is in fine whack”), Hay wrote that Mr. Lincoln’s opponents “are working against him like beaver though; Hale & that crowd but don’t seem to make anything by it. I believe the people know what they want and unless politics have gained in power & lost in principle they will have it.”14

In December, Hale’s own rectitude came under attack for a legal case in which he had obtained the release of a client by appealing to the War Department. Navy Secretary Welles crowed in his diary: “This loud mouth paragon, whose boisterous professions of purity, and whose immense indignation against a corrupt world were so great that he delighted to misrepresent and belie them in order that his virtuous light might shine distinctly, is beginning to be exposed and rightly understood. But the whole is not told and never will be – he is a mass of corruption.”15

In the spring of 1864, Hale was defeated for reelection – by a Republican caucus in his home state that thought it was time to rotate in a new Senator and rotate out an opponent of the Lincoln Administration.. Senate Republicans stripped him of the naval committee chairmanship a few months later – a fate he had only barely escaped the year before. On the night of President Lincoln’s reelection, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus V. Fox commented: “There are two fellows that have been especially malignant to us, and retribution has come upon them both, Hale and [Henry] Winter Davis.” Fox had reason to be bitter, because Hale had vented much of his spleen against him, calling him a “scoundrel & a copperhead.”16 President Lincoln responded: “You have more of that feeling of personal resentment than I…Perhaps I may have too little of it, but I never thought it paid. A man has not time to spend half his life in quarrels. If any man ceases to attack me, I never remember the past against me.”

Despite Hale’s vendetta against the Navy Department and other incendiary comments, President Lincoln nominated him to be Minister to Spain – in the words of Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg, “his many slashing attacks on the Administration now forgotten.”17 Journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “The President says he don’t see why, because a man has been defeated for renomination or re-election for congress, he should be returned on his hands, like a lame duck, to be nursed into something. But he has managed to take care of several such, one being John P. Hale who, after eighteen years’ service in the Senate, packed up his things and got ready to go to Spain where he has $12,000 per annum. Everybody was sorry for Hale, not that he was defeated, but that there should be any good reason – as there was – for his defeat. It was a great pity that a man who was faithful and true to the principles of freedom when it cost something to be a disciple should go down under a cloud.”18

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles complained: “John P. Hale has been nominated and confirmed as Minister to Spain, a position for which he is eminently unfit. This is Seward’s doings, the President assenting. But others are also in fault. I am told by Seward, who is conscious it is an improper appointment, that a majority of the Union Senators recommended him for the French mission, for which they know he has no qualifications, address, nor proper sense to fill. Some of the Senators protested against his receiving the mission to France, but Seward says they acquiesced in his going to Spain. I am satisfied that Seward is playing a game with this old hack. Hale has been getting pay from the War Department for various jobs, and S. thinks he is an abolition leader.”19 Welles acknowledged that Seward asked “Hale to call and see me, and make friends with Fox.”20

The new Minister to Spain was among the visitors to President Lincoln at the White House on the morning of the day he was assassinated. Hale’s daughter was a close friend of assassin John Wilkes Booth – who apparently obtained a pass to attend President Lincoln’s Second Inaugural through Hale. Biographer Sewell wrote “the two men shared a rough good humor which dulled the edges of disagreement and kept their relations cordial. Disagreements of course there had been…Yet Hale repeatedly praised the President as a man of unexcelled ‘honesty and patriotism,’ whose single aim was ‘the welfare of the country’; and not even the senator’s attacks on his Secretary of the Navy kept Lincoln from receiving Hale amicably.”21

Prior to the Civil War, Hale had been a state representative, U.S. Attorney, and member of Congress (Democrat, 1843-1845). He had been the Free-Soil candidate for President in 1852 and his abolitionist sympathies led to a break with the Democratic Party and his nomination by the Liberty Party for President in 1848 and nomination for the President by the Free Soil Party in 1852. He remained a strong advocate of emancipation and black rights during the Civil War. He served as Minister to Spain from 1865 to 1869.

Footnotes

- Richard H. Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 199.

- Michael Burlingame, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, pp. 184-185 (December 28, 1861).

- Burlingame, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, p. 115 (October 14, 1861).

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 195.

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, pp. 198-199.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 376.

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 195.

- Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 374.

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 205.

- Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 376.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, 1859-1866, p. 227 (February 2, 1862).

- Thoedore Calvin Pease, editor, The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, pp. 611-612 (January 9, 1863).

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, pp. 206-207.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 49 (Letter from John Hay to John G. Nicolay, August 7, 1863).

- Richard H. Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 216.

- Sewell, John P. Hale and the Politics of Abolition, p. 207.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 259.

- Noah Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p. 429 (March 22, 1865).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 255 (March 11, 1865).

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 257-58 (March 14, 1865).

Visit

Gideon Welles

Abraham Lincoln and New Hampshire

Gustavus V. Fox