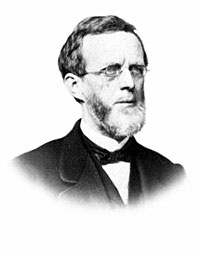

Illinois Senator (Democrat, then Republican, 1855-73) Lyman Trumbull grew estranged from President Lincoln at the outset of the Civil War. Trumbull pushed for stronger Confiscation Acts than Mr. Lincoln liked, but the President approved of Trumbull’s sponsorship of the Thirteenth Amendment that abolished slavery. There were softer moments in the relationship; Trumbull, for example, accompanied Senator Orville H. Browning, Robert Todd Lincoln and the President to the cemetery to bury Willie Lincoln in February 1862.

Historian Allan G. Bogue wrote: “‘A rather tall and spare gentleman with a sandy complexion and gold spectacles,’ Trumbull evidenced his nervous energy in his habit of tearing up little scraps of paper while he smilingly pondered the weaknesses of the arguments developed by colleagues.”1 According to Maine Congressman James G. Blaine, Trumbull’s “mind was trained to logical discussion, and as a debater he was able and incisive.”2

Mr. Lincoln relied on Trumbull as one of his representatives in Washington in the period after his election in 1860 but they drifted apart once the President was inaugurated. The degree of disaffection is illustrated in a letter written from the White House by Mary Lincoln’s cousin, Elizabeth Grimsley in March 1861, “I have not seen Mrs. Trumbull—she sent me word she expected me to call, as that is etiquette, but I concluded in the present state of affairs, that as Mrs. Crittenden, McLean, Foster & various other senators wives had called specially to see me that Mrs. Trumbull might waive ceremony also, if she wished to see me. Trumbull is exceedingly unpopular here and particularly so with the conservative portion of the Republican party.”3 Trumbull also became involved in the manipulations surrounding Mr. Lincoln’s cabinet. He supported fellow Illinoisan Norman Judd, with whom he was allied against the Leonard Swett- faction of the party. Since Judd had supported Trumbull in his election to the Senate in 1855, Mrs. Lincoln opposed Judd’s nomination. Both Judd and Trumbull strongly and unsuccessfully opposed the inclusion of Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron in the cabinet.

“The Judd affair, coupled with other snubs, brought about a considerable cooling off in the personal relations between Trumbull and Lincoln. Their ties had been cordial all through 1859 and especially during the nomination and the election campaign of 1860. Trumbull undoubtedly resented the fact that Lincoln, on the advice of Davis and Ward Hill Lamon, did not take the house in Washington that Trumbull and [Congressman] Elihu B. Washburne had rented for him.”4 Trumbull’s brother-in-law wrote a friend that Trumbull had become alienated from the President: “Mr. Lincoln has not treated Mr. Trumbull as he should and Mr. T. said this morning, that he should not step inside the White House again during Mr. Lincoln’s four years, unless he changed his course.”5

Later, Trumbull was allied with Radical Republicans in Congress, served on the Committee on the Conduct of the War and as chairman of Senate Judiciary Committee. He had serious doubts about President Lincoln’s executive abilities and the desirability of his renomination in 1864, saying that Mr. Lincoln was “too undecided and inefficient to put down the rebellion.”6

“At first glance nothing seemed more improbable than that the quiet scholarly Lyman Trumbull would collaborate with noisy partisans like Wade and Chandler. But appearances were deceiving, and Trumbull succumbed to periodic fits of irritation that clouded his judgment,” wrote historian George H. Mayer. “The special session found him angry at the Southerners and ready to strike back at them… even though he had never before shown any sympathy for the Negro. Trumbull’s vindictive attitude was also aimed at Lincoln, whose only offense had been to win the Presidency. Jealousy did not normally influence Trumbull’s behavior, but the old rivalry of the two men in Illinois made comparisons inevitable, and Lincoln’s good fortune had annoyed him. The ensuing crisis over Sumter and the irresolute response of the President brought all of Trumbull’s resentment to the surface.”7

Trumbull, however was a strong opponent of emancipation. Krug wrote: “In his speech in support of the {First Confiscation bill], Trumbull was one of the first Republican leaders in Congress to declare that the freeing of the slaves was one of the aims of the Civil War. He said: ‘The right to free the slaves of rebels would be equally clear with that to confiscate their property generally, for it is as property that they profess to hold them; but as one of the most efficient means of attaining the end for which the armies of the Union have been called forth, the right to restore them the God-given liberty of which they have been unjustly deprived, is doubly clear.”8

In February 1864, Trumbull wrote an Alton friend: “The feeling for Mr. Lincoln’s reelection seems to be very general, but much of it I discover is only on the surface. You would be surprised, in talking with public men we meet here, to find how few, when you come to get at their real sentiments, are for Mr. Lincoln’s reelection. There is a distrust and fear that he is too undecided and inefficient to put down the rebellion. You need not be surprised if a reaction sets in before the nomination, in favor of some man supposed to possess more energy and less inclination to trust our brave boys in the hands and under the leadership of generals who have no heart in the war. The opposition to Mr. L. may not show itself at all, but if it ever breaks out there will be more of it than now appears. Congress will do its duty, and it is not improbable we may pass a resolution to amend the Constitution so as to abolish slavery forever throughout the United States.”9

In 1865, Trumbull helped to pass 13th Amendment and supported President Lincoln on ratification of Louisiana state government. “Trumbull’s insistence on a constitutional amendment and his opposition to the stand taken by [Charles Sumner, Benjamin Wade] and other radicals that an act of Congress would suffice, exposed him to harsh attacks from the radical wing,” wrote Trumbull biographer Krug. “Lincoln gave the resolution his full support. He approved the inclusion of a declaration in favor of the amendment in the 1864 Republican platform and urged Congress to pass it in his Annual Message to Congress of December 6, [1864]. Faced with the possibility of the defeat of the measure in the House, Lincoln applied all the pressure he could to assure its passage.”10

Under President Johnson, Trumbull moved away from Radical Republicans and favored less stringent Reconstruction policies. He supported Horace Greeley for President in 1872. In 1880 he came full circle and ran for Governor of Illinois as a Democrat.

Trumbull was an attorney with whom Lincoln served in the Legislature in 1840. He was elected by the State Legislature when Abraham Lincoln withdrew from balloting and threw his votes to the anti-slavery Trumbull rather than allow the election of Governor Joel Mattheson, a pro-Douglas Democrat. Mrs. Lincoln detested Trumbull’s wife, Julia Jayne, after Lincoln lost that 1854 Senate race to Trumbull; the two women had previously been very close friends. Mrs. Lincoln carried her feud to the White House, noted Lincoln biographer Michael Burlingame: “Early in the Lincoln administration at a presidential reception, Mrs. Trumbull paused in the receiving line to chat with the First Lady, who instructed the usher, ‘Tell that woman to go on.’ ‘Will you allow me to be insulted in this way in your house?’ Julia Trumbull asked the president.’”11

Trumbull also served as Illinois Secretary of State and State Supreme Court judge. In 1860 Trumbull sought reelection to the Senate rather than fight Lincoln for the support of the Illinois delegation for President.

Footnotes

- Allan G. Bogue, The Earnest Men: Republicans of the Civil War Senate, p. 41.

- James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congressman from Lincoln to Garfield, Volume I, p. 319.

- Harry E. Pratt, editor, Concerning Mr. Lincoln, p. 75.

- Mark M. Krug, Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical, pp. 169-170.

- Krug, Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical, p. 170.

- Krug, Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical, p. 225.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964 , pp. 94-95.

- Krug, Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical, p. 201.

- Horace White, Life of Lyman Trumbull, p. 218 (Letter from Trumbull himself to H. G. McPike, February. 6, 1864).

- Krug, Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical, pp. 219-220.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume I, p. 405.

Visit

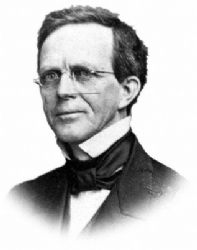

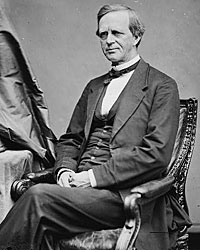

Zachariah Chandler

Benjamin F. Wade

Anson G. Henry

Thirteenth Amendment

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Lyman Trumbull (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Kansas Nebraska and the Senate (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Thirteenth Amendment

Abraham Lincoln and the Radical Republicans