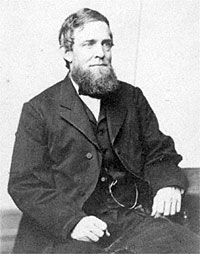

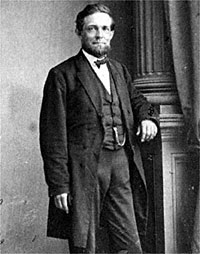

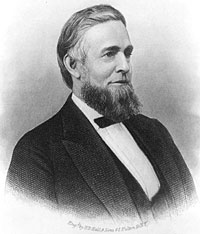

Schuyler “Smiler” Colfax was a Congressman from Indiana (Republican, 1855-69) and Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1863-1869. A Whig and a Know-Nothing before he joined the Republicans, he became more radical on slavery and reconstruction as he grew older. In 1858 he was suspiciously friendly to Mr. Lincoln’s opponent in the Illinois Senate Race, Stephen Douglas. Colfax supported Edward Bates before the 1860 Republican National Convention and sought unsuccessfully to deliver Indiana’s delegates to Bates. Colfax was supported by Chicago Tribune for Postmaster General in 1861, but Indiana’s spot on Cabinet went instead to Caleb Smith—souring Colfax on Lincoln and contributing to Colfax’s shift to Radical Republicanism. Colfax wrote in January 1861 that “Mr. Lincoln said last week that with the troubles before us I could not be spared from Congress—that a new & untried man would fill my place…that Smith had nothing, while I was in office.”1

When Colfax sought the House speakership, President Lincoln initially opposed him, according to historian William Ernest Smith: “…the President begged Montgomery Blair to help him defeat the radical Colfax for Speaker of the House of Representatives in December, 1863. He considered Colfax a little intriguer. Neither Blair nor Welles trusted Elihu Washburne, whom the President preferred to Colfax, but Blair ran the risk of losing the friendship of Colfax to do the bidding of the President. Colfax claimed a friendship of long standing with the Blairs, and upon discovering that the Blairs opposed him for Speaker, he was, in the words, of [Gideon Welles], ‘exceedingly sore.'”2

A hard-working and able debater, “Smiler” was best known for his affability but not his erudition. Teetotaler Colfax held well-attended social events at his home from which the liquor-loving often departed in search of less abstemious homes. Although a talented writer and speaker, Colfax’s education had ended at age 10. Journalist Noah Brooks noted that “it was a cause of mortification to some that when the President’s private secretary appeared at the door of the House with a message, he was invariably addressed by the Speaker a. Sekkertary.'”3

Colfax was present at the White House the night the Emancipation Proclamation was signed on January 1, 1863. After noting that his hand had been shaking a bit when he signed, Mr. Lincoln told Colfax it was not “because of any uncertainty or hesitation on my part; but it was just after the public reception, and three hours’ hand-shaking is not calculated to improve a man’s chirography. The South had fair warning, that if they did not return to their duty, I should strike at this pillar of their strength. The promise must now be kept, and I shall never recall one word.”4

Colfax recorded the President’s response the day after the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864: “I saw him walk up and down the Executive Chamber, his long arms behind his back, his dark features contracted still more with gloom; and as he looked up, I thought his face the saddest one I had ever seen. He exclaimed: ‘Why do we suffer reverses after reverses! Could we have avoided this terrible, bloody war! Was it not forced upon us! Is it ever to end!’ But he quickly recovered and told me the sad aggregate of those days of bloodshed….An hour afterward he as telling story after story to congressional visitors at the White House, to hide his saddened heart from their keen and anxious scrutiny.”5 Colfax was with Lincoln when he was told: “It rests me, after a hard day’s work, that I can find some excuse for saving some poor fellow’s life, and I shall go to be happy tonight.”6

On other occasions, Mr. Lincoln did not hide his heart. One day, the President said to Colfax: Some of my generals complain that I impair discipline and subordination in the army by my pardons and respites, but it makes me rested, after a day’s hard work if I can find some good excuse for saving a man’s life, and I go to bed happy as I think how joyous the signing of my name will make him and his family and friends.”7

Colfax was close to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase but was circumspect in any support he offered to Chase’s ill-fated presidential bid in early 1864. The House speaker was allied with Radical Republicans but never made himself personally obnoxious to Mr. Lincoln as many other did. Colfax did not join the cabal of worried Republicans who wanted Mr. Lincoln to get out of the race in August 1864 but in September he urged reconsideration of the President’s draft call, believing it would hurt Republicans in the October elections in Indiana.

Colfax recalled that in May 1864: “The morning after the bloody battle of the Wilderness, I saw him walk up and down the Executive Chamber, his long arms behind his back, his dark features contracted still more with gloom; and as he looked up, I thought his face the saddest one I had ever seen. He exclaimed: ‘Why do we suffer reverses after reverses! Could we have avoided this terrible, bloody war! Was it not forced upon us! Is it ever to end!’ But he quickly recovered, and told me the sad aggregate of those days of bloodshed. Of course it is perfectly well known that the battle of the Wilderness, however, then claimed as a drawn battle, was, on the contrary, a bloody reverse to our arms, our loss in killed and wounded along being fifteen thousand more than the Confederates. Hope beamed on his face as he said, ‘Grant will not fail us now; he says he will fight it out on that line, and this is now the hope of our country.’ An hour afterward, he was telling story after story to congressional visitors at the White House, to hide his saddened heart from their keen and anxious scrutiny.”8

After the 1864 election, Colfax lobbied hard for Chase’s appointment to become chief justice of the Supreme Court. He wrote in early December, Colfax wrote Chase: “Friday night I had a long talk with the President. He told me of various objections he had heard, which he added, did not influence him, but he repeated them. Some were sinister ones, whose paternity I think I can recognize, & which, I told Mr. Lincoln were unworthy of their author. Another was that your ambition was the presidency, & that a Presl. Candidate should not be C.J. to use it as a steeping stone, impairing the strength and impartiality of the Judiciary. I asked Mr. Lincoln if you had once told him you preferred to be C.J. rather than president. He replied Yes; and I added that, if appointed, I felt certain you would dedicate the remainder of your life to the Bench.”9

Colfax visited President Lincoln on the day he was assassinated and Mr. Lincoln expressed his envy that Colfax was leaving on a trip to California. According to journalist Noah Brooks, he met Colfax after he left the White House and he “tarried with me on the sidewalk a little while, talking about the trip.” President Lincoln had also told Brooks that he had considered moving to California because it would offer for his sons and “when he heard that Colfax was going to California, he was greatly interested in his trip, and said that he hoped that Colfax would bring him back a good report of what his keen and practised observation would note in the country which [Colfax] was about to se for the first time.”10

In a eulogy for Mr. Lincoln, Colfax said: “Murdered, coffined, buried, he will live with those few immortal names who were not born to die; live, as the Father of the Faithful in the times that tried men’s souls; live in the grateful hearts of the dark-browed race he lifted from under the heel of the oppressor to the dignity of freedom and manhood; live in every bereaved circle which has given father, husband, son or friend to die, as he did, for his country; live, with the glorious company of martyrs to liberty, justice and humanity, that trio of Heaven-born principles; live, in the love of all beneath the circuit of the sun, who loathe tyranny, slavery and wrong.”11

As Vice President under Ulysses S. Grant (1869-72), Colfax was associated with the Credit Mobilier scandal. His interest in western economic development and the transcontinental railroad had been long-standing, as his final interview with President Lincoln demonstrated. Although no corruption was ever proved, his reputation suffered. Colfax was denied renomination as Vice President, largely because he had said in 1870 that he intended to retire. Previous to service in Congress, Colfax had been a newspaper editor in South Bend, Indiana. After two decades in Washington, he sustained his family by giving lectures, many of them about Abraham Lincoln.

Footnotes

- William H. Smith, Schuyler Colfax: The Changing Fortunes of a Political Idol, p. 140.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, pp. 243-244.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 31.

- Francis Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 87.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 337-38.

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 339 (Schuyler Colfax).

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men, p. 179.

- Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 337-338 (Schuyler Colfax).

- Smith, Schuyler Colfax: The Changing Fortunes of a Political Idol, pp. 201-202.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 250.

- Smith, Schuyler Colfax: The Changing Fortunes of a Political Idol, pp. 208-209

Visit

Caleb B. Smith

Noah Brooks

Frank Blair

Salmon P. Chase

Abraham Lincoln and Indiana

Members of Congress (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and the Radical Republicans