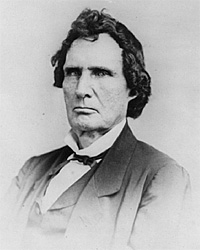

“The Great Commoner,” Thaddeus Stevens was a Pennsylvania Congressman (Whig, Republican 1849-53, 1859-68) and Radical Republican who often pressed President Lincoln on war and emancipation policies. As Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee throughout the Civil War, he pushed tariff and tax policies to finance the war and supported the issuance of currency not backed by gold. An attorney and investor with strong links to banks and railroads, he owned a financially troubled iron works that was destroyed by Confederates before the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. He opposed the influence of moderates such as Secretary of State William H. Seward in the cabinet and General George B. McClellan in the army, while he also opposed the national bank plan of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.

“Thaddeus Stevens was the despotic ruler of the House. No Republican was permitted by ‘Old Thad’ to oppose his imperious will without receiving a tongue-lashing that terrified others if it did not bring the refractory Representative back into party harness,” wrote journalist Ben Perley Poore. “He would often use invectives, which he took care should never appear printed in the official reports…”1

“Mr. Stevens was a tyrant in his rule as leader of the House,” observed Internal Revenue Commissioner George S. Boutwell in his memoirs. “He was at once able, bold and unscrupulous. He was an anti-slavery man, a friend to temperance and an earnest supporter of the public school system, and he would not have hesitated to promote those objects by arrangements with friends or enemies.”2

Stevens confronted President Lincoln on the Administrations errors in 1861 in declaring a blockade of Southern ports, which Stevens felt granted the Confederacy tacit recognition under international law. “Well, that is a fact. I see the point now, but I don’t know anything about the law of nations and I thought it was all right,” President Lincoln told Stevens. “As a lawyer, Mr. Lincoln, I should have supposed you would have seen the difficulty at once,” replied Stevens. “Oh, well,” said Mr. Lincoln. “I’m a good enough lawyer in a western law court but we don’t practice the law of nations up there, and I supposed Seward knew all about it, and I left it him. But it’s done now and can’t be helped, so we must get along as well as we can.”3

Nearly four years later, Stevens returned to see the President in late March 1865 to push for “a more vigorous prosecution of the war.” According to guard William Crook, “The President listened patiently to Mr. Stevens’ argument, and when he had concluded he looked at his visitor a moment in silence. Then he said, looking at Mr. Stevens very shrewdly: ‘Stevens, this is a pretty big hog we are trying to catch, and to hold when we do catch him. We must take care that he doesn’t slip away from us.'”4

“The relations between Stevens and the president-elect started out badly when Lincoln—who had been committed against his wishes—appointed Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania to his cabinet. Stevens, with many others, believed Cameron to be unscrupulous and dishonest,” noted biographer Fawn M. Brodie. Stevens wrote Illinois Congressman Elihu B. Washburne: “I must ever look upon him as a man destitute of honor and honesty.”5 Stevens and others continued to protest the Cameron appointment, even after Mr. Lincoln arrived in Washington in late February 1861. Brodie recalls a story that helped shape the Stevens’ relationship with the President:

During one interview with Lincoln, the president-elected questioned Stevens pointedly: ‘You don’t mean to say you think Cameron would steal?”

“No,’ said Stevens drily, ‘I don’t think he would steal a red-hot stove.”

Lincoln partly as a joke and partly perhaps by way of delicate warning, repeated the statement to Cameron. He was not amused.

Stevens later returned to demand of Lincoln: ‘Why did you tell Cameron what I said to you?”

“I thought it was a good joke and didn’t think it would make him mad.”

“Well, he is very mad and made me promise to retract. I will now do so. I believe I told you he would not steal a red-hot stove. I will now take that back.”6

“Stevens at least subconsciously cherished a resentful belief that he and not Cameron should have sat for Pennsylvania in the Cabinet. He never saw Lincoln when he could help it, and never spoke cordially of him. While close to Chase, whom he had known for full twenty years and with whom he worked closely in meeting the financial needs of the nation, he felt contempt for Seward, and dislike for Montgomery Blair. It would have been well had Stevens devoted himself exclusively to financial affairs; but this iron-willed man held deep convictions about the war, in which force must be used to the utmost, and about the peace, in which the North must show no softness, no spirit of compromise, no magnanimity. In brooding over what he regarded as Lincoln’s delays and excessive generosity, Stevens sometimes exhibited a frenzy of anger,” wrote historian Allan Nevins.7

“Stevens never called at the White House except when he had urgent business with the president; then he found him friendly enough, as a rule. When the congressman had a favor to ask on behalf of one of his constituents, the president usually was only too glad to grant it—a job in the foreign service, a pardon, a discharge from the army,” wrote historian Richard Nelson Current. “These, of course, were political rather than personal favors. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee—which then had powers later to be divided among three committees—Stevens was one of the most influential members of Congress. Without the support of this congressional leader, the president would have had a hard time carrying out any program, civil or military.”8 In August 1864, Mr. Lincoln lost that support. Dissatisfied with a meeting with President Lincoln, Stevens said “If the Republican party desires to succeed, they must get him off the track and nominate a new man.”9

One favor which the President granted Stevens required the President to circumvent an agreement he had made with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton not to issue any commutations of death sentences without the agreement of Stanton. “I am sorry, but I can’t help you, ” Mr. Lincoln told Stevens. “Mr Stanton says I am destroying discipline in the army and I have promised him I will grant no more reprieves without first consulting him.” Stevens protested that no delay was possible and wrote out the reprieve himself, even signing the President’s name and sending it out over the telegraph wires to the appropriate military authorities. When Stanton vehemently protested to Mr. Lincoln that he had broken his word, the President denied he had written the reprieve. “Who did write it?” asked Stanton. “Your friend, Thad Stevens,” replied Mr. Lincoln.10

There was too much difference in their personalities for Stevens and Lincoln to be friends. Biographer Brodie noted: “Lincoln, unlike Stevens, never used frankness as a weapon to deride and humiliate others. Where he was tactful and forbearing with many shades of political opinion, Stevens cut himself off from men whose principles did not largely coincide with his own…..Both men were honest and incisive to a degree almost unknown among politicians. But Lincoln was incomparably abler as a statesman, and also shrewder as a tactician.”11

Stevens’ militant criticism had its uses for the President, argued biographer James Albert Woodburn, “If it be said that such anti-slavery criticisms as Stevens indulged in embarrassed an ever-faithful and overburdened President who was merely biding his time while waiting on public opinion, it may be asked, upon the other hand, how public opinion was ever to be brought to a higher plane, so that the great emancipator might be enabled to do what he desired. His desire as to lead on to that good time when all men might be in the enjoyment of freedom. Could that good time have come at all if the surgent and radical anti-slavery men had all kept still, or had uttered nothing but pleasant and honeyed words for Lincoln and his Cabinet?”12

Still, maintained fellow Pennsylvanian Alexander McClure: “I am quite sure that Stevens respected Lincoln much more much more than he would have respected any other man in the same position with Lincoln’s convictions of duty. He could not but appreciate Lincoln’s generous forbearance even with all of Stevens’ irritating conflicts, and Lincoln profoundly appreciated Stevens as one of his most valued and useful co-workers, and never cherished resentment even when Stevens indulged in his bitterest sallies of wit or sarcasm at Lincoln’s tardiness. Strange as it may seem, these two great characters, ever in conflict, and yet ever battling for the same great cause, rendered invaluable service to each other, and unitedly rendered incalculable service in saving the Republic…Stevens was ever clearing the underbrush and prepared the soil, while Lincoln followed to sow the seeds that were to ripen in a regenerated Union.”13

An astute parliamentarian, able speaker and abusive debater, Stevens later was chairman of the Committee on Reconstruction and led impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, who once called for Stevens’ hanging. Sarcastic and bombastic by turns, he was strongly abolitionist. Stevens found his identity as a spokesman for the oppressed and minorities. He defended runaway slaves for free and fought tirelessly for racial equality, but equivocated on black suffrage. He was quarrelsome and vindictive, but personally generous. He was an advocate of abstinence but an avid gambler. A bachelor who was devoted to his mother, he lived with his mulatto housekeeper. His zealous and nasty disposition won him many enemies. Historian Matthew Josephson wrote: “Though a fanatic outwardly, this harsh and angry old man was possessed of much humor, and could turn in his public speeches from passionate eloquence or close-gripping argument to full mockery of his opponents.”14

Footnotes

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 101.

- George S. Boutwell, Reminiscences of Sixty Years in Public Affairs, Volume I, p. 10.

- Richard Nelson Current, Old Thad Stevens, pp. 146-147.

- Margarita Spalding Gerry, editor, Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, pp. 28-29.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from Thaddeus Stevens to Elihu Washburne, Saturday, January 19, 1861.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 148.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, pp. 340-341.

- Richard Nelson Current, Speaking of Abraham Lincoln, p. 85.

- Current, p. 89.

- Frank A. Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 347.

- Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 145.

- James Albert Woodburn, The Life of Thaddeus Stevens, p. 190.

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 284.

- Matthew Josephson, The Politicos, 1865-1896, p. 19.

Visit

Simon Cameron

Galusha Grow

Edwin M. Stanton

William Henry Crook

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Thaddeus Stevens (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Finance

Thirteenth Amendment