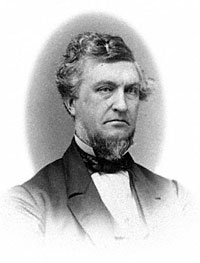

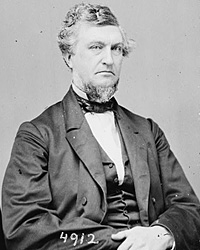

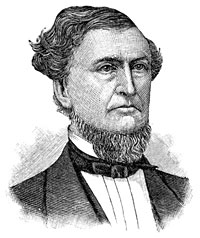

Senator from Michigan (Republican, 1857-1875), Zachariah Chandler was a Radical Republican and a member of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. He was a frequent visitor to the White House with Senators Benjamin Wade and Lyman Trumbull whom John Hay called the “Jacobin Club.” Brash, stubborn, coarse, pugnacious, straightforward, hard-drinking and rich, he used his ideals and money to consolidate his power and oppose slavery. Took an early dislike to General George McClellan and together with senatorial colleagues tried to pressure McClellan and Lincoln to quicker action in November 1861, after which he wrote: “Lincoln means well but he has no force of character. He is surrounded by Old Fogy Army officers more than half of whom are downright traitors and the other one half sympathize with the South.”1

Historian Stephen B. Oates described Chandler: “A restless, rawboned New Englander who’d migrated west to make money and history, he was smooth-shaven and wore an eternally grim expression, with his mouth turned down at the corners.”2 Lincoln aide John Hay recalled in his diary an occasion on November 20, 1863 when the “President called me today & read the following letter which he had written in answer to one from Chandler of Michigan blackguarding Seward Weed Blair & entreating him to stand firm and other trash which lunatics of that sort think is earnest and radical.” 3

Chandler was not an admirer of the president. His opinion deteriorated further when the President pocket-vetoed the Wade-Davis bill on reconstruction on July 4, 1864. Hay recorded in his diary:

In the Presidents room we were pretty busy signing & reporting bills. Sumner was in a state of intense anxiety about the Reconstruction Bill of Winter Davis. Boutwell also expressed his fear that it would be pocketed. Chandler came in and asked if it was signed ‘No.’ He said would make a terrible record for us to fight if it were vetoed: the President talked to him a moment. He said, ‘Mr Chandler, this bill was placed before me a few minutes before Congress adjourns. It is a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way.’ ‘If it is vetoed it will damage us fearfully in the North West. It may not in Illinois; it will in Michigan and Ohio. The important point is that one prohibiting slavery in the reconstructed States.’

Prest. ‘That is the point on which I doubt the authority of Congress to act.”

Chandler. ‘It is no more than you have done yourself.’

President. ‘I conceive that I may in an emergency do things on military grounds which cannot be done constitutionally by Congress.’

Chandler. ‘Mr President I cannot controvert yr position by argument, I can only say I deeply regret it.’

On the way out of the Capitol, Hay questioned the impact of Chandler and others who supported the Wade-Davis bill on Reconstruction: “The Prest answered, ‘If they choose to make a point upon this I do not doubt that they can do harm. The have never been friendly to me & I don’t know that this will make any special difference as to that. At all events, I must keep some consciousness of being somewhere near right: I must keep some standard of principle fixed within myself.’4

Nevertheless Chandler was a pragmatic politician who benefitted from a stream of White House patronage. He was instrumental in arranging a deal whereby John Frémont dropped out of the 1864 presidential contest in return for the dismissal of Postmaster Montgomery Blair from the Cabinet. He shuttled back and forth between Washington and New York in an effort to get an agreement in early September. He met with Mr. Lincoln on September 3 with Senator James Harlan and Congressman Elihu Washburne and again on September 4 by himself. “The President was most reluctant to come to terms but came,” Chandler wrote.5 Chandler himself said President Lincoln was “as unstable as water” and on another occasion, “timid, vacillating, and inefficient.”6 But after Chandler met with Frémont, an agreement was reached and on September 17, Frémont withdrew and on September 23, Blair was asked to quit by the President.

Before entering the Senate, Chandler was a Detroit retail merchant and former mayor who strongly supported the Underground Railroad. He continued in the Senate until 1875 when he became Secretary of the Interior under President Ulysses S. Grant (1875-77), head of Rutherford Hayes’ presidential campaign in 1876 and briefly a member of Congress in 1879 before his death.

Footnotes

- Hans L. Trefousse, The Radical Republicans: Lincoln’s Vanguard for Racial Justiceý, p. 180.

- Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: A Life of Lincoln, p. 378.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 114.

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, pp. 217-218.

- Shelby Foote, The Civil War, Volume III, p. 559.

- Wilmer Harris, Public Life of Zachariah Chandler, p. 61.

Visit

Henry Winter Davis

John C. Fremont

Benjamin F. Wade

James Harlan

George B. McClellan

Charles Sumner

Abraham Lincoln and Michigan

Montgomery Blair

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and the Radical Republicans