In John G. Nicolay’s office, Robert Todd Lincoln announced he had just told his father how to discipline Tad. “I have just had a great row with the President of the United States.” Next door to the Mr. Lincoln’s office, Nicolay’s office was the crossroads of White House activity. “The intense pressure does not seem to abate as yet but I think it cannot last more than two or three weeks longer. I am looking forward with a good deal of eagerness to when I shall have time to at least read and write my letters in peace and without being haunted continually by some one who ‘wants to see the President for only five minutes.” At present this request meets me from almost every man woman and child I met – whether it be by day or night…”1 Nicolay was a good man but he was not a patient man. One of his aides, William O. Stoddard, wrote that Nicolay “could say ‘no’ about as disagreeably as any man I ever knew.”2 Nicolay’s responsibilities were large, as Stoddard observed, “the Private Secretary performed his double duty of defending the President from needless intrusion and of acting almost as a second President in a host of minor matters.”3

Journalist Noah Brooks described Nicolay’s work space as “a small office, very meagerly furnished, and old-fashioned in appearance as, in fact, is all of the upper part of the mansion – the dark mahogany doors, old style mantels and paneled wainscotting being more suggestive of the days of the Madisons and Van Burens that of the present.”4

Such needless intrusions sometimes took strange forms. Many Americans thought they had the solution to the country’s problems. One such young, rather unsophisticated man visited Nicolay’s office. Nicolay reported the “crazy” discussion in a letter to his wife: “I asked him to be seated, after which he at once, without circumlocution and in a very matter-of-fact and business-like way stated the object of his call: ‘I come here, said he, ‘about the business of the war we are in. I am commissioned from On High to take the matter in hand and end it. I have consulted with the Governor of York [sic] State and he has promised to raise as many men of the militia of that State as I need. But as I didn’t want to proceed without authority, I came on here to see General Halleck. I have had an interview him, and he told me he could not give me any men or assistance. That nobody but the President had any authority to act in the case. I have therefore come to see the President and obtain his consent to begin the work. Although no power is competent to stop or impede my progress, I desire to act with the approval of the authorities. I shall take only 2000 men, and shall go south and get Jeff Davis and the other leaders of the rebellion and bring them here to be put in the lunatic asylum, – because they are plainly crazy, and if it is of no use to be fighting with crazy men.” Understandably, Nicolay said the President could not meet with the would-be warrior.5

But some intrusions were welcome. Anna Byers-Jennings recalled interrupting the President on behalf of an imprisoned soldier. “‘Mr. Lincoln, you must pardon this intrusion, but I just could not wait any longer to see you.’ The saintly man then reached out his friendly hand and said: ‘No intrusion at all, not the least. Sit down, my child, sit down, and let me know what I can do for you.'” In granting Mrs. Jennings’ request, Mr. Lincoln also sent a message to the soldier’s blind mother: “And tell his poor old mother I wish to heaven it was in my power to give her back her eyesight so she might see her son when he gets home to her.”6

Nicolay’s daughter later recalled that Nicolay used the same desk at his Capitol Hill home: “The most impressive piece of furniture was the huge desk that my father had used in the White House. He had the good luck to secure it at one of the sales of ‘decayed furniture’ — as they are called – that take place in Washington when some official decides to modernize his office. It is still in my possession. It is about as big as a capacious double bed, without counting four wings that may be extended to make it larger. All told, it offers about thirty-three square feet of flat top, fifteen drawers, and a built-in safe. One of the drawers, uncommonly deep and furnished with a letter-box slit, was used as the mail box in my father’s White House office, being emptied and refilled several times each working day. This desk seemed to bring old days very close to that study on Capitol Hill. My father could almost see Mr. Lincoln’s tall figure pause beside it for a moment as he crossed to his private office.”7

Stoddard, who was later succeeded by Edward D. Neill and Charles H. Philbrick, described Nicolay as “impassable” as having “a fine faculty of explaining to some men the view he takes of any untimely persistency.”8 Stoddard wrote: “People who did not like him because they could not use him said that he was sour and crusty, and it was a grand goo thing that he was.” 9 Shortly after the inauguration in 1861, Nicolay wrote his fiancée: “The first official act of Mr. Lincoln after the inauguration was to sign my appointment as Private Secretary….As the work is now it will be a very severe tax on both my physical and mental energies, although so far I have felt remarkably well. By and by, in two or three months, when the appointments have all been made, I think the labor will be more sufferable. John Hay and I are both staying here in the White House. We have very pleasant offices and a nice large bedroom, though all of them sadly need new furniture and carpets. That too we expect to have remedied after a while.”10

Because John Nicolay occupied the busy gate house those impatient to see the President came to Nicolay. Within days of starting his new job, Nicolay wrote: At present this request meets me from almost every man, woman and child I see, whether by day or night, in the house or on the street.”11 Stoddard sometimes had to substitute for Nicolay in his absence. “On the whole, I think he was much better qualified for it than I. He was older, more experience, harder, had a worse temper, and was decidedly German in his manner of telling men what he thought of them. I was more reticent, and Hay was more diplomatic,” noted Stoddard.12

In this office the President’s correspondence arrived and was organized by his secretaries; only 1-2% of the 200 or more daily letters actually reached the President. Some were referred. Some were trashed. Nevertheless, the volume sometimes threatened to overwhelm the secretaries, who needed additional clerical help. William O. Stoddard, an assistant presidential secretary to sign land patents, occupied a desk here early in the Lincoln Administration. Writing about his experiences in Inside the White House in War Times, Stoddard reported the daily routine:

“Here is our special work coming in. The big sack that [Louis Bargdorf], the President’s messenger, is perspiring under, contains the morning’s mail. What a pile it makes, as he pours it out upon the table! Why, no, it is no larger than usual. Why, no, it is no larger than usual. Heaps of newspaper? Yes, and no. We have to buy the newspapers we really need and read, like other people, but a host of journals, all over the country, supply the White House gratis. Open them if you wish to learn how the course of human events, and of the President in particular, is really influenced. How very many of these sagacious editors have blue-and-redded their favorite editorials, and have underscored their most stinging paragraphs!

That is because they fear lest Mr. Lincoln may otherwise fail to be duly impressed. He might even not see the points! His first complete failure was an attempt he made to watch the course of public opinion as expressed by the great dailies East and West. After he gave up reading them, he had a daily brief made for him to look at, but at the end of a fortnight he had not once found time to glance at it, and we gave it up.

Besides all other difficulties, the editors are dancing around the situation in such a manner that no man can follow them without getting too dizzy for regular work.

Put aside the journals now, and take up the kind of written papers which come through the post in bundles and bales, mostly sealed a great deal. Do you see what they are? That pile is of applications for appointments to offices of every name and grade, all over the land. They must be examined with care, and some of them must be briefed before they are referred to the departments and bureaus with which the offices asked for are connected. We will not show any of them to Mr. Lincoln at present.

That other pile contains matter that belongs here. They are ‘pardon papers,’ and this desk has the custody of them, but their proper place, one would think, is in the War Office. That is where they all must go, after a while; but the President wishes them where he can lay his hands upon them, and every batch of papers and petitions must be in order for him when he calls for it. He is downright sure to pardon any case that he can find a fair excuse for pardoning, and some people think he carries his mercy too far There was a vast amount of probable pardon, for instance, in a bale of papers which should have been here day before yesterday. It came from a guerrilla-stricken district in the West, for the pardon of the worst guerrilla in it, and the petitions were largely and eminently and influentially signed. There came up to the President office in great haste a large and eminent and influential delegation, and the papers were sent for. Somehow or other they were not here. They may have been at the War Office, but the people there denied it. They may have been somewhere else, but the people there denied it, and the delegation had to go away, and the application still hangs fire.

‘What did you say? A telegram from —? You don’t tell me! Has that man been actually hung? It’s a pity about his papers! Seems to me – well, yes, I remember now. I know where—‘

‘Well, if I did, I guest I wouldn’t; not now; but if they’re ever called for again, and they won’t be, they ought to be where they can be found.’

‘Certainly, certainly. But it’s just as well that one murderer has escaped being pardoned by Abraham Lincoln. Narrow escape too! The merest piece of luck in all the world!’

There is no sameness in the sizes of the White House mails. Some days there will be less than 200 separate lots, large and small. Some days there will be over 300. Anyhow, every envelope must be opened and its contents duly examined.

Are they all read? Not exactly, with a big wicker wastebasket on either side of this chair. A good half of each mail belongs in them, as fast as you can find it out. The other half calls for more or less respectful treatment, but generally for judicious distribution among the departments, with or without favorable remarks indorsed upon it.

It is lightning work…

Written acknowledgments of the receipt and disposal of papers are frequently necessary, and it is well that you have the right to frank letters through the mails, for you never could get the President to spend time in franking.13

Most of the correspondence was handled by the secretaries although the President sometimes dictated as well as wrote his own letters. John Hay described the working relationship of the President with his secretaries in a letter to William Herndon in 1866:

He pretended to begin business at ten o’clock in the morning but in reality the anterooms and halls were full before that hour – people anxious to get the first axe ground. He was extremely unmethodical; it was a four-years struggle on Nicolay’s part and mine to get him to adopt some systematic rules. He would break through every Regulation as fast as it was made. Anything that kept the people themselves away from him he disapproved – although they nearly annoyed the life out of him by unreasonable complaints & requests.

He wrote very few letters. He did not read one in fifty that he received. At first we tried to bring them to his notice, but at last he gave the whole thing over to me, and signed without reading them the letters I wrote in his name. He wrote perhaps half-a-dozen a week himself – not more.

Nicolay received members of Congress, & other visitors who had business with the Executive Office, communicated to the Senate and House the messages of the President, & exercised a general supervision over the business.

I opened and read the letters, answered them, looked over the newspapers, supervised the clerks who kept the records and in Nicolay’s absence did his work also. When the President had any rather delicate matter to manage at a distance from Washington, he very rarely wrote, but sent Nicolay or me.14

Nicolay’s office was also a natural gathering place for those waiting to see the President or exchange news and gossip. On April 29, 1861 John Hay recorded in his diary: “Going into Nicolay’s room this morning, [Carl] Schurz and [Jim] Lane were sitting. Jim was at the window, filling his soul with gall by steady telescopic contemplation of a Secession flag impudently flaunting over a roof in Alexandria. ‘Let me tell you,’ said he to the elegant Teuton, ‘we have got to whip these scoundrels like hell, C. Schurz. They did a good thing stoning our men at Baltimore and shooting away the flag at Sumter. It has set the great North a-howling for blood, and they’ll have it.'”15

William Agnew Paton recalled meeting the President in Nicolay’s office. The 14-year-old presented a card that mentioned was the nephew of an acquaintance of the President: “My uncle was well known to Mr. Lincoln and thus use of his name doubtless facilitated my admission to the office of the private secretary to the President, where I found the chief magistrate of my country at a desk in conversation with a gentleman, the only other occupant of the room, who was, as I afterward learned, the Minister of France. When I entered the office the President was seated in a curiously constructed armchair made after a design suggested by himself. The left arm of this unique piece of furniture began low and, rising in a spiral to form the back, terminated on the right side of the seat at the height of the shoulders of the person seated thereon. Mr. Lincoln had placed himself crosswise in this chair with his long legs hanging over its lower arm, his back supported by the higher side. When the attendant who had presented my card to the President, and had then ushered me into the secretary’s office, closed the door behind me and I found myself actually in the presence of Abraham Lincoln, I had the grace to feel embarrassed, for then I realized that I, a mere schoolboy, was intruding upon the patience and good-nature of a very busy overwrought man, the great and honored President of a country in the agony of a great civil war. Noting my hesitation, Mr. Lincoln very gently said: ‘Come in, my son.’ Then he arose, disentangling himself, as it were, from the chair, advanced to meet me, and it seemed to me that I had never beheld so tall a man, so dignified and impressive a personage, and certainly I had never felt so small, so insignificant, ‘so unpardonably young.'”16

On May 6, 1861, John Hay recorded in his diary: “The President came into Nicolay’s room this afternoon. He had just written a letter to [Hannibal Hamlin], requesting him to write him a daily letter in regard to the number of troops arriving, departing, or expected, each day. He said it seemed there was no certain knowledge on these subjects at the War Department, that even Genl. Scott was usually in the dark in respect to them.”17

Bugs could be a summertime hazard. In June 1864, Hay wrote Nicolay : “I am alone in the White pest-house. The ghosts of twenty thousand drowned cats come in nights through the South Windows.”18 Nicolay himself wrote his fiancée:

My usual trouble in this room is from what the world is sometimes pleased to call ‘big bugs’, oftener humbugs. But at this present writing (10 o’clock p.m. Sunday night) the thing is quite reversed and little bugs are the pest. The gas lights over my desk are burning brightly and the windows of the room are open, and all bugdom outside seems to have organized a storming party to take the gas lights, in numbers that seem to exceed the contending hosts at Richmond. The air is swarming with them, they are on the ceilings, the walls and the furniture in countless numbers, they are buzzing about the room, and butting their heads against the windowpanes, they are on my clothes, in my hair, and on the sheet I am writing on. There are all here, the plebeian masses as well as the great and distinguished members of the oldest and largest patrician families, the Millers, the Roaches, the Whites, the Blacks and yes, even the wary and diplomatic foreigners from the mosquito kingdom.

They hold a high carnival, rather a perfect saturnalia. Intoxicated, and maddened and blinded by the brightness of the light, they dance and rush and fly about in wild gyrations until they are drawn into the dazzling fatal heat of the gas flame. Then they fall to the floor burned, maimed and mangled to the death, to be swept out into the dust and rubbish by the servant in the morning. I could go along with a long moral and discourse with profound wisdom about it’s being not altogether unapt miniature picture of the folly, the madness, intoxication, and fate too of many big bugs whom even in this room I witnessed buzzing and gyrating around the central sun and light and source of power of the government.”19

Nicolay’s job was taxing and trying. Writing to his fiancée, John Nicolay said: “There is a sort of sameness in everything that surrounds us here that makes it almost impossible to get oneself interested in anything but that which somehow pertains to the war or the troubles of the country. The subject is of intense interest, but when one is situated as I am, where they themselves cannot do anything whatever to advance or retard it, the contemplation of it grows irksome at times. [In another letter] This everlasting frittering away of hours and days is one of the many disagreeable features of life here…With all my self-taught calmness and self-possession I sometimes get so fidgety and nervous that I am strongly tempted to do one of two things; either to go off somewhere into the Northwest back-woods where I couldn’t hear of war and revolution for a year or two, or else to get into the most active and hottest part of the fight, wherever that might be. This being where I can overlook the whole war and never be in it – always threatened with danger and never meeting it–constantly worked to death yet doing (accomplishing) nothing, I assure you grows exceedingly irksome, and I sometimes think even my philosophy will not save me. It is a feeling of duty and not one of inclination that keeps me here. The man who lives in a cabin at the head of some hollow, with corn-bread enough to keep him from starving, and quinine enough to keep off the ague, has quieter nerves and more present satisfaction than I have.”20

Footnotes

- Letter from John Nicolay to Therena Bates, Washington, March 24, 1861, Nicolay Papers.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 151 from William Stoddard, “White House Sketches, No II,” New York Citizen, Aug. 25, 1866.

- William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln, p. 243.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 82-83 (November 7, 1863)

- Helen Nicolay, “The Education of a Historian,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. II, No. 3, September 1944, pp. 129-130.

- Anna Byers-Jennings, “A Missouri Girl’s Visit with Lincoln,” in Wilson, editor, Lincoln Among His Friends, pp. 376-378.

- Helen Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary, p. 257.

- Burlingame, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 109.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 134.

- Helen Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary, pp. 74-75.

- Carl Sandburg, The War Years, Volume I, p. 165.

- Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 187.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, pp. 13-15 .

- Douglas Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editors, Herndon’s Informants, p. 331.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 13.

- Victoria Radford, Meeting Mr. Lincoln, p. 109-110 from William Agnew Paton, “The Card That Brought an Interview,’ Century magazine, December 1913.

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 18.

- Michael Burlingame, editor: At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 85.

- Benjamin P. Thomas, “The President Reads His Mail,” The Many Faces of Lincoln, pp. 125-126.

- Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary, p. 116.

Visit

John Hay

John Nicolay

William O. Stoddard

John Hay’s Office

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

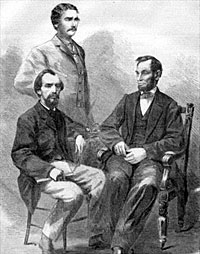

John G. Nicolay (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln’s Secretaries