Many of the most important decisions of the war were made here at noon meetings on Tuesdays and Fridays – a structure that was instituted after Cabinet members complaints about the lack of scheduled meeetings. And virtually all meetings of the cabinet were held here. “These meeting are wonderfully secret affairs. Only a private secretary may enter the room to so much as bring in a paper. No breath of any ‘Cabinet secret’ will ever transpire, so faithfully is the seal of this room guarded,” wrote presidential aide William Stoddard. 1 There was an informality to the proceedings which some cabinet members never appreciated. They wanted a more formal structure in which they were consulted on all the important issues facing the country. On September 16, 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary:

Whilst the other members of the Cabinet were absorbed in familiarizing themselves with their duties and in preparing themselves for impending disaster, the Secretary of State [William H. Seward], less apprehensive of disaster, spent a considerable portion of every day with the President, patronizing and instructing him, hearing and telling anecdotes, relating interesting details of occurrences in the Senate, and inculcating his political party notions. I think he has no very profound or sincere convictions. Cabinet-meetings, which should, at that exciting and interesting period, have been daily, were infrequent, irregular, and without system. The Secretary of State notified his associates when the President desired a meeting of the heads of Departments. It seemed unadvisable to the Premier – as he liked to be called and considered – that the members should meet often, and they did not. Consequently there was very little concerted action.

At the earlier meetings there was little or no formality; the Cabinet-meetings were a sort of privy council or gathering of equals, much like a Senatorial caucus, where there was no recognized leader and the Secretary of State put himself in advance of the President. No seats were assigned or regularly taken. The Secretary of State was invariably present some little time before the Cabinet assembled and from his former position as the chief executive of the largest State in the Union, as well as from his recent place as a Senator, and form his admitted experience and familiarity with affairs, assumed, and was allowed, as was proper, to take the lead in consultations and also to give tone and direction to the manner and mode of proceedings. The President, if he did not actually wish, readily acquiesced in, this. Mr. Lincoln, having never had experience in administering the Government, State or National, deferred to the suggestions and course of those who had. Mr. Seward, was not slow in taking upon himself to prescribe action and doing most of the taking upon himself to prescribe action and doing most of the talking, without much regard to his modest chief, but often to the disgust of his associates, particularly Mr. [Edward Bates], who was himself always courteous and respectful, and to the annoyance of Mr. [Salmon Chase], who had, like Mr. Seward, experience as a chief magistrate. Discussions were desultory and without order or system, but in the summing-up and conclusions the President, who was a patient listener and learner, concentrated results, and often determined questions adverse to the Secretary of State, regarding him and his opinions, as he did those of his other advisers, for what they were worth and generally no more. But the want of system and free communication among all as equals prevented that concert and comity which is really strength to an administration.

Each head of a Department took up and managed the affairs which devolved upon him as he best could, frequently without consulting his associates, and as a consequence without much knowledge of the transaction of other Departments, but as each consulted with the President, the Premier, from daily, almost hourly intercourse with him, continued, if not present at these interviews, to ascertain the doings of each and all, though himself imparting but little of his own course to any. Great events of a general character began to impel the members to assemble daily, and sometimes General Scott was present, and occasionally Commodore Stringham; at times other were called in. 2

Meetings of the Cabinet were normally held in the President’s office on Tuesdays and Fridays. Members of the cabinet who wanted a comprehensive discussion of major problems facing the administration were often disappointed because the President dealt with many important problems directly with the cabinet secretary involved. Their frustration sometimes boiled over — as when Secretaries Chase and Stanton attempted to rally their peers in order to force the President to fire General George B. McClellan in late August 1862.

The President roamed around the room during Cabinet meetings rather than sitting formally at the large table in the middle of the room.. There was no particular order — or regular attendees at the Cabinet meetings — as Secretary of the Navy Welles frequently complained to his diary on April 22, 1864: “Neither Seward nor Chase nor Stanton was at the Cabinet-meeting to-day. For some time Chase has been disinclined to be present and evidently for a purpose. When sometimes with him, he takes occasion to allude to the Administration as departmental,– as not having council, not acting in concert. There is much truth in it, and his example and conduct contribute to it. Seward is more responsible than any one, however, although he is generally present. [Secretary of War Edwin Stanton] does not care usually to come, for the President is much of his time at the War Department, and what is said or done is communicated by the President, who is fond of telling as well as of hearing what is new. Three or four times daily the President goes to the War Department and into the telegraph office to look over communications. 3

Among the important cabinet meetings were:

December 25, 1861 on the Trent Affair

December 18, 1862 on attempt to force Seward out of the Cabinet.

September 22, 1862 Proclamation of Draft Emancipation Proclamation.

Post-Election Cabinet Meeting on November 11, 1864

Final Cabinet Meeting on April 14, 1865

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 11.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 136-137.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles,Volume II, p. 16.

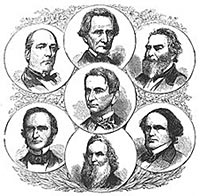

Visit

William H. Seward

Gideon Welles

Salmon P. Chase

Edwin M. Stanton

Cabinet & Vice Presidents

Abraham Lincoln and the Cabinet

Abraham Lincoln and Foreign Affairs