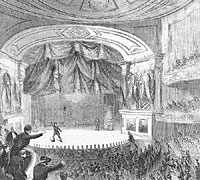

Ford’s Theater on 10th Street between E and F Streets, was the site of President Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865. The President often visited there to relax and enjoy his love of the theater. The building was formerly a Baptist church and had been turned into a theater in late 1861, remodeled, suffered considerable fire damage in December 1862 and then refurbished by owner John T. Ford.

One frequent theater companion of the President was Schuyler Colfax who said they went to Ford’s theater “to regale ourselves of an evening, for we felt the strain on mind and body was often intolerable.”1 Newspaper editor John W. Forney, observed that “Mr. Lincoln liked the theatre not so much for itself as because of the rest it afforded him. I have seen him more than once looking at a play without seeming to know what was going on before him. Abstracted and silence, scene after scene would pass, and nothing roused him until some broad joke or curious antic disturbed his equanimity.”2

Another fellow theatergoer was assistant secretary John Hay, who recorded this visit on December 19, 1863: “Tuesday, December 15th The President took Swett, Nicolay & me to Fords with him to see Falstaff in Henry IV. Dixon came in after a while. Hackett was most admirable. The President criticized H.’s reading of a passage where Hackett said, “Mainly thrust at me,” the President thinking it should read “Mainly thrust at me.” I told the Prest tho’t he was wrong, that “mainly” merely meant “strongly” fiercely.”3

William O. Stoddard also recalled seeing Hackett play Falstaff. There was an interruption in the play when a spectator saw Mr. Lincoln, arose during the performance and cried: “There he is! That’s all he cares for his pooor soldiers.’ Seconds later, a uniformed immigrant shouted: “De President haf a right to his music! Put out dot feller! De President ees all right! Let him haf his music!” And indeed, fellow soldiers ousted the President’s critic. 4

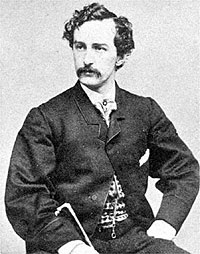

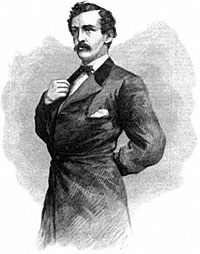

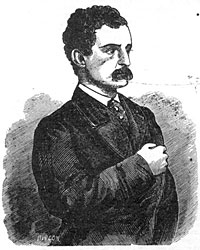

A month earlier in November 1863, Mr. Lincoln attended a performance of The Marble Heart, in which John Wilkes Booth played the romantic lead. Mary Clay remembered a performance she attended with Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln:

“In the theater President and Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and I, Mr. Nicolay and Mr. Hay, occupied the same box which the year after saw Mr. Lincoln slain by Booth. I do not recall the play, but Wilkes booth played the part of villain. The box was right on the stage, with a railing around it. Mr. Lincoln sat next to the rail, I next to Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Sallie Clay and the other gentlemen farther around. Twice Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln’s face; when he came a third time I was impressed by it, and said, ‘Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?’ At the same theater, the next April, Wilkes Booth shot our dear President. Mr. Lincoln looked to me the personification of honesty, and when animated was much better looking than his pictures represent him.”5

White House security guard William Crook later recalled that President Lincoln told him several hours before the assassination: “It has been advertised that we will be there, and I cannot disappoint the people. Otherwise I would not go. I do not want to go.” Crook thought the statement odd because, in the words of the theater doorkeeper, Mr. Lincoln went to plays “to take a laugh.”6

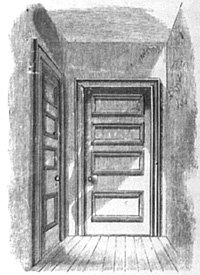

When the President and Mrs. Lincoln arrived on the fatal Friday night, they were accompanied by Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, the daughter of Senator Ira Harris of New York. They were late, but the play, Our American Cousin, was interrupted when they entered the presidential box so the band could play “Hail to the Chief” and the audience could deliver a standing ovation to the couple. Shortly after 10:15, John Wilkes Booth left a nearby bar and entered the theater, where he had drilled a peephole to observe the President’s box. Since guard John Parker had deserted his post, Booth made an easy entrance to the box, timing his assassination to coincide with a mirthful moment on stage.

The security on such occasions was minimal, Sergeant Smith Stimmel later wrote: “President Lincoln flatly refused to have a military guard with him when he went to places of entertainment or to church in the city. He said that when he went to such places, he wanted to go as free and unencumbered as other people, and there was no military guard with him the night of his assassination. The only person [other than Parker] that could have protected him in the theater the night of his assassination was a civilian who was employed at the White House, known as the carriage footman. When the President went out with his family, and sometimes with invited guests, to places of entertainment, this footman would go along and ride on the seat with the driver. When they reached their destination, he would hop down and render such assistance as a handy man could.”7 Parker himself deserted his post near the door to the presidential box in order to get a better view of the performance.

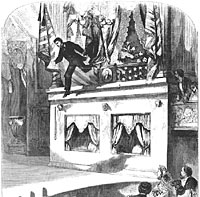

The President was seated in a rocking chair, holding hands with his wife. Booth unloaded a single shot from his derringer into the back of the President’s head, cut Major Rathbone with a hunting knife when he tried to interfere and then himself jumped to the stage. Booth caught his spur on the American flag in front of the box and broke his leg as he hit the stage floor. Yelling “Sic temper tyrannis,” he limped off stage to the rear of the theater where an employee held the reins of Booth’s horse. Inside the theater, cries of “Shoot him!” and “Kill the murderer” rang out.

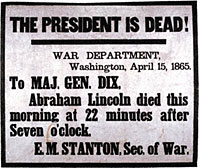

Pandemonium reigned until access was gained to the presidential box, which Booth had blockaded. Attempting to restore calm, the play’s leading actress, Laura Keene told the audience: “For God’s sake have presence of mind and keep your places and all will be well. Responding to a plea from Clara Harris, she then brought water up to the presidential box.8 “Dr. Charles A. Leale, a young Army assistant surgeon, pounded at the door leading to the vestibule outside the box until the faint and bleeding Rathbone removed the bar Booth had placed against it. Leale found the President slumped in the rocker with the sobbing Mrs. Lincoln supporting his head. Finding no pulse, he eased the long body to the floor, according to historian Robert H. Fowler, “Below, another physician, Dr. Charles Taft, fought his way to the stage and was lifted high enough to get his hands on the balustrade and struggle his way into the box. They cut open Lincoln’s coat and shirt, thinking he might have been stabbed. Seeing no wound on the chest, Dr. Leale ran his fingers gently through the coarse black hair until he found the bullet hole at the back of the head. He removed a clot of blood, thinking this would relieve pressure on the brain. Dr. Leale then bent over Lincoln, and through mouth-to-mouth respiration, forced air into his lungs. He and Dr. Taft also tried to stimulate the heart, pressing against the upper stomach and pumping the arms.”9

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, p. 291.

- John W. Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 272.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 128.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 165.

- Katherine Helm, Mary Wife of Lincoln, p. 243.

- William Crook, Through Five Administrations, p. 67.

- Smith Stimmel, Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 89-90.

- Allen C. Clark, Abraham Lincoln in the Nation’s Capital, p. 109.

- “The Tragedy at Ford’s Theater,” by Robert H. Fowler, McPherson, James M., editor. Battle Chronicles of the Civil War: 1865, p. 79-80.

Visit

Schuyler Colfax

William Henry Crook

John W. Forney

John Hay

John Wilkes Booth and Assassination

Lincoln Obituary from the New York Times

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

Abraham Lincoln and Literature