Mr. Lincoln died on Saturday, April 15. On Tuesday, April 18, 1865 President Lincoln lay in state in the East Room on an eleven-foot high catafalque designed by Commissioner of Public Building Benjamin French. Preparations had gone on virtually uninterrupted since the President’s body had been moved back to the White House. The workmen were on temporary reassignment from their regular jobs at a Treasury Department construction site. One friend of the family protested that work should cease because “Mrs. Lincoln is very much disturbed by noise. The other night when putting them up every plank that dropped gave her a spasm and every nail driven reminded her of a pistol shot.”1

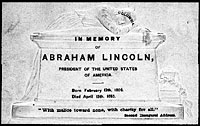

Mourners lined up outside White House, waiting for the 9:30 A.M. opening of the White House gate. Many had to wait more than six hours to pay their respects. About 25,000 walked through the South Portico into the entry hall and the Green Room before entering the East Room, which had been darkened for the occasion. The mirrors in the room were covered — as they were for other funerals held there — and the frames swathed in black crepe. Black cloth also covered the walnut, lead-lined coffin — which was only two inches longer than the 6-4 President. A silver plate on the lid read: “ABRAHAM LINCOLN, 16TH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, BORN FEBRUARY 12, 1809, DIED APRIL 15, 1865.” On each side of the coffin were four silver handles and four shamrocks formed by silver tacks. The coffin itself sat on a platform covered in black cloth. Flowers from the White House grounds and greenhouse encircled the coffin and perfumed the air. Two dozen ranking Union officers formed an honor guard. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote in Washington in Lincoln’s Time:

Mourners lined up outside White House, waiting for the 9:30 A.M. opening of the White House gate. Many had to wait more than six hours to pay their respects. About 25,000 walked through the South Portico into the entry hall and the Green Room before entering the East Room, which had been darkened for the occasion. The mirrors in the room were covered — as they were for other funerals held there — and the frames swathed in black crepe. Black cloth also covered the walnut, lead-lined coffin — which was only two inches longer than the 6-4 President. A silver plate on the lid read: “ABRAHAM LINCOLN, 16TH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, BORN FEBRUARY 12, 1809, DIED APRIL 15, 1865.” On each side of the coffin were four silver handles and four shamrocks formed by silver tacks. The coffin itself sat on a platform covered in black cloth. Flowers from the White House grounds and greenhouse encircled the coffin and perfumed the air. Two dozen ranking Union officers formed an honor guard. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote in Washington in Lincoln’s Time:

“The great room was draped with crape and black cloth, relieved only here and there by white flowers and green leaves. The catafalque upon which the casket lay was about fifteen feet high, and consisted of an elevated platform resting on a dais and covered with a domed canopy of black cloth which was supported by four pillars, and was lined beneath with fluted white silk. In those days the custom of sending ‘floral tributes’ on funeral occasions was not common, but the funeral of Lincoln was remarkable for the unusual abundance and beauty of the devices in flowers that were sent by individuals and public bodies. From the time the body had been made ready for burial until the last services in the house, it was watched night and day by a guard of honor, the members of which were one major-general, one brigadier-general, two field officers, and four line officers of the army and four of the navy. Before the public were admitted to view the face of the dead, the scene in the darkened room – a sort of chapelle ardente – was most impressive. At the head and foot and on each side of the casket of their dead chief stood the motionless figures of his armed warriors.

When the funeral exercises took place, the floor of the East Room had been transformed into something like an amphitheatre by the erection of an inclined platform, broken into steps, and filling all but the entrance side of the apartment and the area about the catafalque. This platform was covered with black cloth, and upon it stood the various persons designated as participants in the ceremonies, no seats being provided…2

For eight hours, the public passed by the coffin. Only then were special groups of visitors allowed to pay their respects. After mourners departed about 7:30 P.M., carpenters built platforms all around the East Room for guests invited to the funeral. The noise nearly drove Mary Todd Lincoln crazy — indeed, it so disturbed her that at her request it was not dismantled until after she moved out of the White House in May.

The funeral itself was held shortly after noon on Wednesday, April 19, 1865. About 600 guests entered the same way the public had the day before – through the crepe-covered South Portico and the Green Room and into the candle-lit East Room. There was a cross of lilies near Mr. Lincoln’s head; General Ulysses S. Grant was seated on this side. At the opposite end of the coffin was seated Robert and Tad Lincoln and some of their mother’s relatives. The cabinet stood on one side of the room behind President Andrew Johnson and former Vice President Hannibal Hamlin. An Episcopalian priest, Rev. Charles Hall, began the service with the words: “I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.” He read from Corinthians 15:20: “But now is Christ risen from the dead.” Dr. Phineas Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, delivered the eulogy:

“I have said that the people confided in the late lamented President with a full and loving confidence. Probably no man since the days of Washington was ever so deeply and firmly imbedded and enshrined in the very hearts of the people as Abraham Lincoln. Nor was it a mistaken confidence and love. He deserved it – deserved it well – deserved it all. He merited it by his character, by his acts, and by the whole tenor, and tone, and spirit of his life. He was simple and sincere, plain and honest, truthful and just, benevolent and kind. His perceptions were quick and clear, his judgments were calm and accurate, and his purposes were good and pure beyond a question. Always and everywhere he aimed and endeavored to be right and to do right. His integrity was thorough, all-pervading, all-controlling, and incorruptible. It was the same in every place and relation, in the consideration and the control of matters great or small, the same firm and steady principle of power and beauty that shed a clear and crowning luster upon all his other excellences of mind and heart, and recommended him to his fellow citizens as the man, who, in a time of unexampled peril, when the very life of the nation was at stake, should be chosen to occupy, in the country and for the country, its highest post of power and responsibility.”3

Among the five dozen ministers present were Bishop Matthew Simpson of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and Dr. E. H. Gray, the Baptist chaplain of the Senate and pastor of the E. Street Baptist church.. Bishop Simpson gave the opening and Dr. Gray gave the closing prayer. (Simpson subsequently performed the marriage of Robert Todd Lincoln.)

After the guests departed, 12 army sergeants carried the coffin out to the waiting funeral hearse drawn by six white horses that brought the coffin to the Capitol. Thousands of Union soldiers, including many who left hospital beds to participate, filed in behind the funeral procession — which was led by French and a contingent of black soldiers who arrived late and turned around in time to lead the parade. At the end of the parade behind the dignitaries and the soldiers were 40,000 newly-freed blacks, holding hands. Over 100,000 more Americans lined the streets. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported: “Every window, housetop, balcony and every inch of the sidewalks on either side was densely crowded with a mournful throng to pay homage to departed worth. Despite the enormous crowd the silence was profound. It seemed akin to death it commemorated. If any conversation was indulged in, it was in suppressed tones, and only audible to the one spoken to. A solemn sadness reigned everywhere. Presently the monotonous thump of the funeral drum sounded in the street, and the military escort of the funeral car began to march past with solemn tread, muffled drum and arms reversed.”4

Capitol architect Thomas Walter was displeased that the Lincoln funeral interrupted work on completing the Capitol. Anthony Pitch wrote: “The constant booming of the cannons ‘began to operate on my nerves,’ Walter wrote irritably to his wife. When he tried to walk down the avenue, he was blocked by the crowds. Frustrated by masses of people besieging the rotunda, he sneered, ‘I do not consider any of this nonsense as doing honor to our president, and I have not in any way participated in it, not even so much as to be a mere looker on.’”5

The next day, the President’s casket lay in state at the Capitol — and another 25,000 paid their last respects. On Friday, it began the long journey north and west to Springfield for interment aboard an eight-coach train. Two caskets were aboard – one belonged to the President’s beloved son Willie who had been originally buried in Washington.

Footnotes

- Jane H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 248.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, p. 259.

- Wayne Temple, Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet, pp. 325-326.

- Allen Culling Clark, Abraham Lincoln in the National Capital, p. 117.

- Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!,” p. 230.

Visit

Benjamin Brown French

Andrew Johnson

Mary Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

Rev. Phineas D. Gurley

Funeral

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

The Funeral Train of Abraham Lincoln

Funeral Train (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Matthew Simpson

Matthew Simpson (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Phineas Gurley (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)