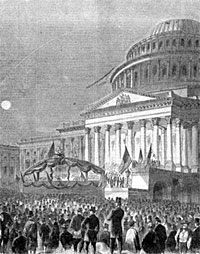

President-elect Lincoln had not visited the Capitol since 1849 when he left the city at the end of his single term in the U.S. Congress. His subsequent failure to be appointed by President Taylor as U.S. Land Commissioner had precluded any need to return. When he arrived again in Washington in February 1861, he paid courtesy calls on Congressional leaders prior to his inauguration. Since he had last visited it, the Capitol had been expanded and two wings for the Senate and House had been added; the new dome, however, had not yet been completed. The other major difference was that the Union was disintegrating and many Southern members of Congress had departed or preparing to depart. William O. Stoddard, soon to be a presidential secretary, recalled seeing the U.S. flag flying over the Capitol and “when a strong glare of light was thrown across the flag to make it visible, the effect was all that could be asked for at a time when so much treason was being plotted in that very building.”1

Congress was then at the end of its standard December-March session. Congress was informal, as English journalist William Howard Russell wrote when he visited it on July 5, 1861, the day that the President sent his war message to Capitol Hill:

All the encaustics and the white marble and stone staircases suffer from tobacco juice, though there is a liberal display of spittoons in every corner. The official messengers, doorkeepers, and porters wear no distinctive bade or dress. No policemen are on duty, as in our Houses of Parliament; no soldiers, gendarmerie, or sergents-de-ville in the precincts; the crowd wanders about the passages as it pleases, and shows the utmost propriety, never going where it ought not to intrude.

It was a hot day; but there was no excuse for the slop coats and light-coloured clothing and felt wide-awakes worn by so many Senators in such a place. They gave the meeting an aspect of a gathering of bakers or millers; nor did the constant use of the spittoons beside their desks, their reading of newspapers and writing letters during the despatch of business, or the hurrying to and fro of the pages of the House between the seats, do anything but derogate from the dignity of the assemblage, and, according to European notions, violate the respect due to a Senate Chamber.

The House of Representatives exaggerates all the peculiarities I have observed in the Senate, but the debates are not regarded with so much interest as those of the Upper House; indeed, they are of far less importance. Strong-minded statesmen and officers – Presidents or Ministers – do not care much for the House of Representatives.”2

Massachusetts Congressman Henry L Dawes recalled meeting Mr. Lincoln on the morning in February 1861 when the president-elect arrived in Washington incognito: “I could never quite fathom his thoughts, or be quite sure that I saw clearly the line along which he was working. But as I saw how he overcame obstacles and escaped entanglements, how he shunned hidden rocks and steered clear of treacherous shoals, as the tempest thickened, it grew upon me that he was wiser than the men around him. He never altogether lost to me the look with which he met the curious and, for the moment, not very kind gaze of the House of Representatives on that first morning after what they deemed a pusillanimous creep into Washington. It was a wary, anxious look, of one struggling to be cheerful under a burden of trouble he must keep to himself, with thought afar off or deep hidden which he could not impart even to the representatives of ht nation to whose Chief magistracy he had been called and for whom he was to die.”3

The Civil War, patronage concerns, and military problems complicated the lives of members of Congress, according to historian Allan G. Bogue: “To the inconveniences of boardinghouse or hotel life and the unpleasantness of the Washington climate, there was no added the pressure of greatly increased work. The committee room and late sessions held the senators in thrall until it was pure ecstasy to ride a horse or drive a buggy out to visit one of the state regimental encampments in company with friends or army offices. Less happy but even more essential were the visits to army hospitals, which became routine once the grim game was begun in earnest across the rolling Virginia countryside.”4

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the U.S. Capitol was in the midst of a major expansion — with a truncated dome overlooking the city. As a symbol of the Union’s future, work continued on it during the war. In an interview with Union Chaplain John Eaton, the President said: “If people see the Capitol is going on, it is a sign we intend this Union shall go on.”5

Shortly before President Lincoln’s First Inaugural on March 4, 1861, aide John Hay ascended to the base of the Capitol’s yet-unconstructed dome. In a newspaper article, Hay presented an unvarnished portrait of the city: “It is a good place – this light, aerial gallery, iron-railed – from which panoramically to view this sprawling, chaotic town. Seen from this point, the city unrolls its dusty magnificences of distance; the stupendous harmonies of its design reveal themselves in broad avenues, which converge upon the capitol as all the roads of the Roman empire converged upon that golden milestone by the Pincian gate; moreover, distance lends enchantment here as elsewhere. The town is a congeries of hovels, inharmoniously sown with temples, as the Napoleonic tapestries were sown with golden bees, but something in the dust, the remoteness, the sunlight, touches them into respectability, if it does not glorify them. For the chief thoroughfare of a capital it would be difficult to conceive of a meaner street in architectural adornments than Pennsylvania avenue, but from this point it takes on the stately airs of a grand Appian Way among thoroughfares. Very straight, very broad, and, seen from a distance, it makes a false pretense of being splendid, which it is not, but only escapes squalor by a hair’s breadth. Why did they attempt to build a city where no city was ever intended to be reared? It will never be a capital, except only in name; never a metropolis like Rome, or London, or Paris.” Then Hay sketched an uncomfortable vision, writing that Washington “will sometime, of course, be clustered about with historic memories. Caesar will be slain in the capitol, and Brutus harangue the roughs from the terrace.”6

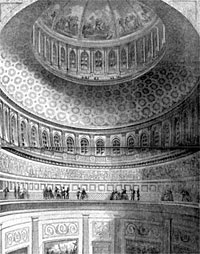

In 1863, journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “During the present summer the interior of the Capitol has been renovated, refitted, cleansed of the dirt of the Thirty-Seventh Congress, and made ready for the dirt and wickedness of the incoming legislators. The halls of the Senate and House have been thoroughly purified, the lobbies and corridors whitened, and much of the unfinished fresco painting in the Senate wing has been completed. The Capitol exterior has advanced considerably toward completion. The great bronze doors, or valve, for the principal front on the Capitol, cast in Munich, Germany, after models by [Randolph] Rogers and costing $40,000, have arrived and will be put in place before the opening of the next session of Congress. The magnificent portico of the Senate wing is nearly completed, the sculpture for the pediment being in place, and the work above it being pushed forward so that the whole front of that wing will be done before December 1.”7

Brooks went to describe how the Capitol dome almost came to be painted bronze rather than white: “The dome is receiving the ornaments of iron which now encumber all of the ground about the Capitol, and scrolls, volutes, flowers, and other cast-iron nondescripts are fast finding their places on the immense bulb which soars far above the massive pile of marble. It is the intention of [Thomas U.] Walter, the architect, to have the molus on the summit of the dome complete, and the statue of Liberty, which will surmount it, in its place by November 1; but as the work is an arduous one, it may not be done before the next session commences. At present the statue of Liberty, which is twenty feet high and weighs nearly 15,000 pounds, is lying dismembered on the ground, her ladyship’s head, arms, legs, etc., gigantic in their way, receiving the attentive admiration of the daily throng of sight-seers at the Capitol. It will be ‘Make way for Liberty’ when she begins to go up, however, for her breadth of beam is truly tremendous. The superintending authorities are profoundly agitated just now to decide upon the color for the dome when it shall be complete. At present it is white, but as its design precludes the idea that it might be marble, it is suggested by Walter that its metallic appearance be further decided by painting it a light bronze, and that will probably be the conclusion reached by the rest of the parties concerned.”8

“Despite Civil War shortages of men and materials, the fifth and final section of the bronze crowning statue of Freedom (nineteen feet seven inches tall), by Thomas Crawford, was put in place on December 2, 1863,” wrote historian Daniel J. Boorstin. “With a strict order against speechmaking, this statue of an armed Freedom triumphant in war and peace was dedicated by a thirty-five-gun salute. The dome was finished when Constantino Brumidi completed his Apotheosis of Washington in December 1865.”9 Washington historian Constance McLaughlin Green wrote: “One of the stirring moments of those four long winters of war came on December 3, 1863, when, to the boom of cannon from every fort about Washington, Thomas Crawford’s bronze ‘Freedom,’ hoisted by horses, ropes and pulleys, rose to her place on the crowning cupola of the new Capitol dome.”10

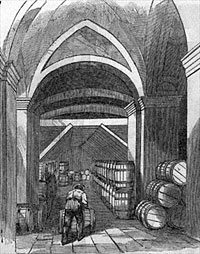

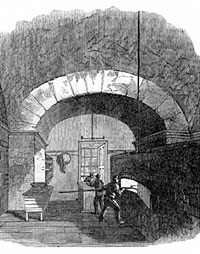

During the war, the Capitol fulfilled a number of non-legislative functions. During the panic that afflicted the city after the fall of Fort Sumter, the Congress was one of the federal buildings used to house Union troops. Because of its height, it was the natural site of an artillery emplacement. The basement of the Capitol was used as a central bakery for the Union troops in 1861 and 1862 until President Lincoln ordered it moved. In the summer of 1862, it was used a hospital when Union troops engaged in battles nearby at Bull Run and Antietam.

Footnotes

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 69.

- Fletcher Pratt, editor William Howard Russell, My Diary, North & South, p. 192

- Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, pp. 4-5 (Henry L Dawes).

- Allan G. Bogue, The Earnest Men: Republicans of the Civil War Senate, p.27.

- John Eaton, Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen: Reminiscences of the Civil War, p. 89.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, p. 49 (New York World, March 1, 1861).

- Noah Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, pp. 241-242 (October 9, 1863).

- Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p. 243 (October 9, 1863).

- Daniel Boorstin, Cleopatria’s Nose, p. 94.

- Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington: Village and Capital, 1800-1878, p. 268.

Visit

John Hay

John Nicolay

William O. Stoddard

Stephen A. Douglas

Andrew Johnson

Hannibal Hamlin

Congressional Visitors

Noah Brooks

Abraham Lincoln and Radical Republicans