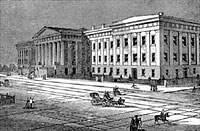

Located at Seventh and F Street, across from the Post Office, the Patent Office had been visited by Abraham Lincoln and his son Robert when Mr. Lincoln was a congressman and seeking to patent his invention for moving boats over river shoals. British novelist Anthony Trollope called it “a grand building, with a fine portico of Doric pillars at each of its three fronts. These are approached by flights of steps, more gratifying to the eye than to the legs. The whole structure is massive and grand, and, if the streets round it were finished, would be imposing. The utilitarian spirit of the nation has, however, done much toward marring the appearance of the building, by piercing it with windows altogether unsuited to it, both in number and size. The walls, even under the porticoes, have been so pierced, in order that the whole space might be utilized without loss of light; and the effect is very mean.”1

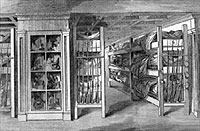

Historian Philip Van Doren wrote: “The north wing had just been completed, and the building formed an enormous quadrangle with an open court in the center. Its high-ceilinged second story was designed for displaying the thousands of patent models that had been accumulating ever since the disastrous fire of 1836 destroyed the earlier ones. It was also a national museum, where the original copy of the Declaration of Independence, Franklin’s printing press, and various relics, of Washington, Lafayette, Jefferson, Jackson, and other historic figures were on public view.” Van Doren added for the 1865 Inaugural Ball: “All four of the enormous second-story rooms, each approximately 270 feet long and 60 feet wide, were used for the ball. The south wing, with its elaborate and colorful English tiled floor, tall pillars, and large glass showcases, was the main entrance. The east wing was used as a promenade leading to the north wing, which was to be the main ballroom. The elaborate supper was served at midnight in the west wing.”2

The biographers of Lincoln’s second secretary of the Interior, John Palmer Usher, wrote: “The principal concern of the Department was the administration of four subjects: Indian affairs, the public domain, patents and pensions. Lesser matters within its jurisdiction were the compilation of the federal census, the maintenance and construction of federal buildings in the Capital, care and improvement of the city streets, water supply and drainage, the national hospital for the insane, the Institute for the Deaf and Blind, and the Washington Board of Police. During the war, the Department also served as temporary barracks, exhibit hall, and depository for articles captured from the Confederacy. In the midst of the alarm created by Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania, it even generated an ‘Interior Regiment’ from its officers and clerks.”3

At the beginning of the Civil War, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment was headquartered here and was visited by President Lincoln, who raised the Union flag over the building. Much of the building, which also had space for the Interior Department, was used as a hospital during the war. Journalist Noah Brooks visited the Patent Office Hospital with the President and his wife. The President gently rebuked a soldier who laughed at a tract he had been given by a woman visitor. “Mr. President,” replied the wounded soldier, “how can I help laughing a little? She has given me a tract on the ‘Sin of Dancing’ and both of my legs are shot off?”4

William O. Stoddard, the President’s assistant for Land Office patents, was technically stationed here. He recalled later that his nominal boss, Judge J. M. Edmonds, the Commissioner of the General Land Office and a close friend and counselor of the President, was making an unaccountable number of shut-the-door visits to the Executive Office. He was one of the shrewdest of long, hawk-nosed, twinkle-eyes, sharp, smiling old men, and was said to be one of the best informed and most capable politicians in the country.” After one of these visits to the President’s Office, Edmonds came to Stoddard’s room and invited him to the Patent Office that night for a secret meeting where was formed the Union League of America, which organized Union League Clubs around the country. Apparently, noted Stoddard, the meeting was “something with which [Mr. Lincoln] did not wish to appear connected in any way.”5

At a subsequent meeting of the “Central Council of Twelve of the Union League,” the opposition to a banking bill then before Congress was discussed. President Lincoln’s quiet support for the act was explained by Stoddard to Wisconsin Senator Timothy Howe, an opponent of the legislation. “Do you mean to say, of your own knowledge, that he regards or that he would look upon any man who voted against the bill as a public enemy,” asked Howe. Stoddard denied the proposition but stated, “He would only feel, and would be compelled to say, that the men who defeat the bill are cutting off pay and supplies for the armies in the field, starving the soldiers, forcing the abandonment of campaigns, preventing enlistments, acting as reinforcements to Lee and as supporters of Jeff Davis.” Howe instantly reversed his position.6

On February 22, 1864, President Lincoln, his wife and oldest son Robert attended the opening of a fair at the Patent Office for the benefit of the Christian Commission. Mr. Lincoln was asked to give a speech, which he attempted not to do, concluding, “If I make any mistakes it may do both myself and the nation harm. It is difficult to always say sensible things. I therefore hope that you accept my sincere thanks for this charitable enterprise in which you are engaged. With the expression of the gratitude of mine, I hope that you will excuse me.” Mary Lincoln was said to have told Mr. Lincoln after his speech: “That was the worst speech I ever listened to in my life. How any man could get up and deliver such remarks to an audience is more than I can understand. I wanted the earth to sink and let me go through.”7

A new wing for the Patent Office was built during the war and the building was transformed once again for the Second Inaugural ball that was held in that wing on March 6, 1865. Brooks wrote for his California newspaper: “[S]pace will not permit me to tell…all about the Inauguration Ball; how such another display of laces, jewelry, silks and feathers, gold lace and things was never seen, no, not since the world began. The President was there, also Mrs. President, and the Cabinet, and Joe Hooker, and [Admiral David] Farragut, and such another mob of hungry people I am ashamed to say that when supper was announced and the big wigs had fed and gone, they rushed in, pushed the tables from their places, snatched of whole turkeys, pyramids, loaves of cake and things, smashed crockery and glassware, spilled oyster and terrapin on each other’s heads, ruined costly dresses, tore lack furbelows, made the floor all sticky with food, and behaved in the almost invariably shameful manner of a ball-going crowd at supper. The ball in the great unoccupied Hall of Patents, Interior Building, and three similar halls were thrown open, making a complete quadrangle of four lighted and decorated halls, a fine sight, but all spoiled by the disgusting greediness of this great American people.”8

Another journalist, Ben Perley Poore, later wrote that the hall in the Patent Office was “brilliantly lighted and dressed with flags. Mr. Lincoln and Speaker Colfax entered together, followed by Mrs. Lincoln upon the arm of Charles Sumner. Mr. Lincoln wore a full black suit, with white kid gloves, and Mrs. Lincoln was attired in white silk, with a splendid overdress of rich lace, point lace bertha and puffs of silk, white fan and gloves. Her hair was brushed back smoothly, falling in curls upon the neck, while a wreath of jasmines and violets encircled her head. Her ornaments were of pearl. Having promenaded the entire length of the room, they mounted the few steps leading to the seats placed for them upon the dais, while the crowd gathered densely in front of them.”9 The Lincoln’s eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, took time off from his military duties to escort his future wife, Mary Harlan, to the party.

Perley was more detailed in his description of the mob scene that surrounded the supper. “The tables having been instantly filled up, all the spaces between the large glass cases containing the office property were soon crowded to their utmost capacity. Many a fair creature dropped upon the benches with exclamations of delight, while their attendants sought to supply them from the table, to which they had to fight their way. Those who could not get seats stood around in groups, or sank down upon the floor in utter abandonment from fatigue.”10

According to Stanley Kimmel, “During this melee, a squabble occurred among employees in the kitchen which called for the interference of the police. Hearing the cooks swearing at one another, an officer entered just in time to see the most boisterous of the group struck by a large plate of chicken salad thrown by another of the ‘kitchen cabinet. The injured one, having been responsible for the rumpus was taken before a Justice of the Peace who fined him one dollar and lectured him upon the impropriety of his conduct.”11

The First Inaugural Ball took place nearby in the “Muslin Palace,” erected especially for the occasion near Judiciary Square. “Like all similar functions it was more of a reception, and ‘dress parade’ where the President is on exhibition, and he and his family march through the ranks of observers and critics, and are then at liberty to leave the scene, ” observed Elizabeth Todd Grimsley.12

President Lincoln entered with Washington Mayor James Berret while Mrs. Lincoln made her entrance with Senator Stephen Douglas, with whom she later danced. The President shook hands for over two hours before retiring — an estimated 2000 hands. The Evening Star reported: “The last scene of the levee was a tragic one. The mob of coats, hats and caps left in the hall had somehow got inextricably mixed up and misappropriated, and perhaps not one in ten of that large assemblage emerged with the same outer garments they wore on entering. Some thieves seem to have taken advantage of the opportunity to make a grand sweep, and a very good business they must have done. Some of the victims utterly refused to don the greasy, kinky apologies for hats left on hand, tied up their heads in handkerchiefs and so wended their way sulkily homeward…”13

The 1864 Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City reported that “This is one of the finest buildings in Washington. It occupies the whole square between E and F and Seventh and Eighth streets, the position being a very central one. The erection of the edifice was commenced in 1839, Mr. Robert Mills being the architect; and in 1855 it was extended under the direction of Mr. Walter. It is built of white marble. The style is what is known as the Palatial, and the order of architecture is a modified Corinthian. The building rests on a rustic basement, and is three stories high. Length from north to south, 800 feet. Depth from east to west, 204 feet.” T. Loftin Snell wrote:

“The Patent Office building is one of superior finish and elegance. It occupies the entire space between Seventh and Ninth and F and G streets. The style of architecture is Doric, and the finish is so exceedingly plain, and yet the building, in all its architectural details, is so grand and majestic that it excites the admiration of all who behold it. The building extends 410′ feet from Seventh to Ninth street, and 275 feet from F to G street, and has fronts on all four of the streets named. All of the building, except the south part, is built of crystallized marble, the centre of the part named being brown sandstone, painted to correspond with the other portions of the building. The inner quadrangle of the structure is 265 feet long by 135 feet wide. T he base is of freestone; and the basement is fitted up with offices for the clerks connected with the Department, and with rooms for models of large size, &c. A semicircular stone staircase runs from this basement to the upper stories, of which there are two. The east, west, and south sides of the edifice are ornamented with porticos. The broad platform of the south portico is reached by a flight of 28 granite steps, and it is studded with double rows of fluted columns. These columns are of the Doric order. They are made of freestone, and are 16 in number, and each column is 18 feet in circumference. The roof of the building is flat, and is covered with copper. The interior of this magnificent edifice is as grand as the exterior, and the arrangements are complete in all their details. The third story is occupied by cases and shelves containing models of patents. The room thus occupied measures 1,350 feet in length on its outer surface, and occupies the whole third story of the immense building, running all around the quadrangle. Here may be seen not only models of all articles patented, but a vast number of curiosities and relics of Revolutionary days, among which are the printing press of Franklin, and articles of personal property which belonged to Washington. Besides, the room itself is worthy of careful examination, as indeed is the entire building.”14

Footnotes

- Anthony Trollope, North America, p. 311.

- Philip Van Doren Stern, An End to Valor, p. 23.

- Elmo R. Richardson and Alan W. Farley, John Palmer Usher, Lincoln’s Secretary of the Interior, pp. 32-33.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie and the War Years, p. 403.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 101.

- Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 110.

- John Y. Simon, Harold Holzer and William D. Pederson, editors, Lincoln, Gettysburg and the Civil War, Frank J. Williams p. 68.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, pp. 169-170.

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 161.

- Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 162.

- Stanley Kimmel, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p. 168.

- Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, “Six Months in the White House,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Volume 19 (Oct.-Jan., 1926-27), p. 47.

- Allen C. Clark, Abraham Lincoln in the Nation’s Capital, p. 16.

- T. Loftin Snell, The Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City, pp. 25-27.

Visit

Caleb Smith

William O. Stoddard

John Palmer Usher

Elizabeth Todd Grimsley

Second Inaugural