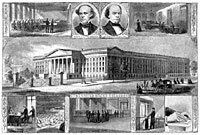

The Treasury Building was located just east of the White House — where Pennsylvania Avenue makes a right turn on its path from the Capitol to the White House. The building used during the Civil War was the third one that the Treasury Department occupied on the site — the first two had burned and the new one was still uncompleted. “These public offices stand with their side to the street, and the whole length is ornamented with an exterior row of Ionic columns raised high above the footway. This is perhaps the prettiest thing in the city, and when the front to the north has been completed, the effect will be still better. The granite monoliths which have been used, and which are to be used, in this building are very massive,” wrote British novelist Anthony Trollope.1

With the outbreak of the war in 1861, the building assumed a new importance. The Fifth Massachusetts Regiment was bivouacked here early in the War. Treasury clerks were formed into a militia unit and the building was prepared to be the last bastion of Union government in the District.

More importantly, the financial requirements of the war required a great expansion of the Treasury Department’s responsibilities – with an accompanying growth of personnel, many of them women. The Treasury Department was one of the prime sources of work opportunities for women in Washington. Mary Elizabeth Massey wrote: that “the ‘government girls’ were to become a permanent part of the Washington scene, and many women employed in business and industry elsewhere would be able to hold their jobs after peace was restored.”2 Union officer William E. Doster wrote in his diary: “A notable feature on the streets of the capital is the female Government employees; especially the Treasury girls. They are generally young and of good families – for it takes some influence to get into a department. There are many black sheep among them, however. They get $600 a year which is little when board is hard to get at $30 per month, and an ordinary room costs $20 per month.”3

Many of whose clerks deserted for the South. Journalist William A. Croffut recalled: “Among those that remained there were hardly any efficient phonographers – not half a dozen in the whole city. One day Governor Ramsey said to me, ‘See here! It just occurs to me. You’re a shorthand writer, ain’t you? Well, Chase wants you.’ At this he straightway took me to the Treasury Department and introduced me to its chief. My examination consisted merely of the question, ‘What state are you from?’ I was appointed with the understanding that I might continue my newspaper work.”4

Construction on the Treasury Department continued during the Civil War and not completed until 1869. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote in 1863 that “work on the Treasury extension is going on rapidly, and already one or two bureaus have been moved into their new quarters. The old system of many small rooms has been abolished, and each department or bureau is put in one great room by itself, well provided for light, ventilation, and comfort, and the whole being under the immediate supervision of the chief clerk or controller of the bureau. The private rooms and office of the Secretary of the Treasury are truly palatial in style and finish. The walls are richly decorated in gold and colors, the passages paved with tessellated marble and the floors are to be covered with rich carpets of appropriate design.”5 Brooks described “Chase’s private offices” as furnished with “Axminister carpets, gilded ceilings, velvet furniture, and other luxurious surroundings which go to hedge about a Cabinet Minister with a dignity quite appalling to the unaccustomed outsider.”6

President Lincoln did not often visit. (However, after the assassination of President Lincoln in 1865, President Andrew Johnson met with the Cabinet here. For the next six weeks until May 25, when Mrs. Lincoln moved out of the White, Johnson kept his office here.) Lincoln preferred to walk west to War Department than east to the treastruary Department. Lincoln did visit after the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, and according to Chase in a letter to his son-in-law, “The president came into my office and told me of it about two yesterday afternoon. He was more grieved and indignant than I have ever seen him.”7

President Lincoln invested virtually all of his presidential salary in governmental bonds and relied on Treasury officials to take care of the transactions. Treasury official Levi Gould recalled that “After the seven-thirty bonds were offered for subscription, he came over, I should think, about once a month, sat down beside me, counted out what money he was able to spare from his salary, and invested the same in these bonds, while they lasted, or in a second issue of similar character. He waited until they were duly issued to his order, and then took them away.”8

Mr. Lincoln paid little attention to these investments, however, until he visited the Treasury Department on June 10,1864 to straighten out his finances. “By this time, Lincoln’s purchases of government securities had become confusing to him. With problems of the war occupying his every waking minute, he had not time for personal affairs. Therefore he asked Salmon P. Chase to have his purchases consolidated into one type of government bonds. Chase promised to have this done. Lincoln made a list of his holdings, pocketed everything at hand, walked over to the Treasury Department and emptied the contents of his pockets on Chase’s desk,” according to Harry E. Pratt, author of The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln.9 Maunsell B. Field, assistant secretary of the Treasury, described Lincoln’s arrival:

I happened once to be with the Secretary when the President, without knocking, and unannounced, as was his habit, entered the room. His rusty black hat was on the back of his head, and he wore, as was his custom, an old gray shawl across his shoulders…I said good morning to Mr. Lincoln, and then, as was the established etiquette when the President called, withdrew…In less than five minutes I was summoned to return to the Secretary. Mr Schuckers, his private secretary entered the room at the same time that I did. The President was gone, and there was lying upon one end of Mr. Chase’s desk a confused mass of Treasury notes, Demand notes, Seven-thirty notes, and other representatives of value. Mr. Chase told us that this lot of money had just been brought by Mr. Lincoln, who desired to have it converted into bonds.10

Lincoln’s holdings in government obligations totaled $54,515.07, and he brought along a bag of gold amounting to $883.30. Chase turned the securities over to George Harrington, Assistant Secretary, for investment. In addition to the gold Harrington found five different kinds of assets: $16,000 of 7-30 notes; $26,181.40 of Certificates of Deposit; $8,000 of 5-20 bonds; $4,044.67 in salary warrants, and $489 in greenbacks.11 Field noted that the President’s assets totaled “$68,000″, which was certainly a large sum for Mr. Lincoln to have saved from his salary in three years. Possibly a good deal of this money may have been anonymous gifts. However, it may be said that there was very clever financiering done in the White House in those days, about which the President was supposed to have little or no knowledge. He only knew that the establishment was conducted in a marvelously economical manner.”12

Field came to the Treasury Department in early October 1863 when plans for Chase’s 1864 presidential aspirations were beginning to heat up. Field later wrote: “When speaking of Mr. Chase’s Presidential aspirations, I am reminded, as Mr. Lincoln used to say, of a little story. When I first went to Washington, the Secretary occupied for his office a room on the south side of the Treasury building, with a beautiful outlook down the Potomac. Soon afterward it was proposed that he should remove to certain elaborately ornamented and elegantly furnished rooms on the west side of the building, which had been arranged for his occupation by Mr. Mullett, the architect of the Department. Mr. Chase had consented to make the change; but after the new rooms were ready he delayed removing. Several times he appointed a day to do so, but when the time came he had changed his mind. One afternoon, while he was still hesitating, I was standing with him at one of the windows of the largest of the new rooms which faced the Executive Mansion. Turning to me, he asked me to assign one sufficient reason why he should change his quarters. I told him that there was, if he should come to these offices, he would always be able to keep his eye upon the White House!”13

In the Southwest corner of the Treasury Building were located a few rooms that served as the offices of the Attorney General. His tiny staff consisted only of a deputy, six clerks and a laborer/messenger at the beginning of the Civil War. The Attorney General “did not head a government department; the Department of Justice would not be created until 1870. And until Congress acted in August 181, the Attorney General had no authority to control the actions of the United States Attorneys in the various judicial districts. He could and did advise them on points of law or on government policy. But he gave advice, not direction.”14

The 1864 Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City reported that “This is a noble structure, and is situated on Fifteenth street, just south of the State Department. Pennsylvania avenue is here cut off, but continues again above the State Department, and thence runs west to Georgetown. The Treasury building is of granite ; over 460 feet in length and 266 feet wide. The east front has colonnade of Ionic columns, 300 feet long. These columns are 42 in number. Projecting porticos decorate the north and south ends of the building. A more imposing structure than this cannot be found in the city. The granite of which it is constructed is from Dix Island, on the coast of Maine. Prior to 1855 the building occupied by the Treasury Department was 336 feet long, with a depth at the centre of 190 feet, but at that time projections, which gives it its present length, were added. There is also a portico about the centre of the east front. The building is not yet fully completed according to the plan of the architect, but workmen are continually employed upon it.”15

Footnotes

- Anthony Trollope, North America, p. 311.

- Mary Elizabeth Massey, Women in the Civil War, p. 131.

- William E. Doster, Lincoln and Episodes of the Civil War, p. 240.

- William A. Croffut, An American Procession 1855-1914: A Personal Chronicle of Famous Men, p. 52.

- Noah Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p. 241 (October 9, 1863).

- Noah Brooks, Lincoln Observed,, pp. 124-125

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 471.

- Harry E. Pratt, The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln.

- Ellis Paxon Oberhholtzer, “A Midnight Conference, Scribner’s Magazine, Volume 45, 1909, p. 149.

- Maunsell B. Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and Some Women, pp. 282-283.

- Pratt, The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln, p. 129.

- Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and Some Women, pp. 282-284.

- Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and Some Women, p. 281.

- William H. Rehnquist, All the Laws but One, p. 41

- T. Loftin Snell, The Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City, pp. 24-25.

Visit

Salmon P. Chase

William Pitt Fessenden

Hugh McCulloch

Salmon Chase’s House

Treasury Building (off site link)

William Johnson