The War Department, located where the Old Executive Office Building now stands to the west of the White House, was a frequent nocturnal destination for President Lincoln’s perambulations. Edwin M. Stanton had enlarged and rehabilitated the building when he became Secretary of War in 1862; he raised its height from two to four stories. One building, however, could hardly contain all the functions of the wartime War Department. By the end of the war, the department was spread over 11 buildings.

Given the Secretary’s penchant for hard work and efficiency, the department’s headquarters was a beehive of activity — including those seeking favors from the Secretary of War. But the President did not stand on stand on ceremony when he had a problem to resolve. He would pick up his hat and walk to the War Department to see Stanton, Assistant Secretary Peter Watson, Assistant Secretary Charles A. Dana, or other military officials. Stanton’s “customary position in his office was standing at a high, long desk, facing the principal entrance to the room, and open to all who had the right of audience, for he shunned every semblance of privacy in his office,” wrote journalist Noah Brooks.1 According to General John Pope, Stanton, Secretary Stanton “stood behind a high, slightly inclined table…with a piece of paper before him and a pencil in his hand. Around the room stood his visitors, who stepped up one by one to this high table, stated his business as briefly as possible and in the hearing of everybody, and received a prompt and final answer as rapidly as words would convey it.” Pope approved Stanton’s abrupt manner with ‘self-seekers or those in search of favors for others. The necessity of taking a whole room full of strangers into their confidence much abbreviated all such communications, and whilst the secretary’s popularity among these people and their followers was not successfully established by such methods, there is no doubt that the public interests were greatly subserved.”2

.

According to Stanton biographer Fletcher Pratt, Mr. Lincoln “heard of what went on at these morning hours and often, when business permitted, with the remark that he was ‘going to see old Mars quell disturbances,’ he would stroll over to the War Office to stand silently, watching the human drama flow past.”3 The imperious ways of Secretary Stanton were less amusing to lesser mortals, including Mr. Lincoln’s own secretaries. Stanton, according to historian Allan Nevins “antagonized most of the people who did business with him. Don’t send me to Stanton to ask favors, John Hay once begged [John] Nicolay: ‘I would rather make a tour of a small pox hospital.'”4

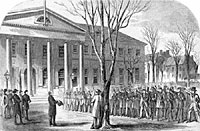

Stanton also scared the War Department staff. Lincoln biographer Benjamin Thomas wrote: “Business in the War Department began officially at nine o’clock. As Stanton’s carriage turned off Pennsylvania Avenue around that time, the doorkeeper would stick his head inside and announce: ‘The Secretary.’ The word spread; stragglers and loungers scurried to their desks and the place quivered with activity. Alighting from his carriage, Stanton was usually beset by favor-seekers, waiting on the sidewalk. He might stop for a word with a soldier or a needy-looking woman, but he would curtly tell the others to go to his reception room upstairs.”5

“The furniture of Stanton’s office was of the simplest kind. The only luxury was an old haircloth lounge, from which the covering was half-worn,” wrote Stanton’s biographer Frank A. Flower. “On this, during great battles or important military manoeuvres, when he dared not be away from the telegraph instrument day or night, he secured little rest. Here, too, during many an anxious night, Lincoln stretched himself while reading despatches and consulting with the Secretary.”6

When Mr. Lincoln arrived at his office, the imperious Stanton sometimes had to adopt an uncustomary position – yielding to higher authority. Stanton biographers Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman told a story about a confrontation between the two men about the draft allocation for some Confederate soldiers who volunteered to serve on the Western frontier: “Stanton said: ‘Now, Mr. President, those are the facts, and you must see that your order cannot be executed.’ Lincoln, sitting on a sofa in Stanton’s office with his legs crossed, answered firmly: ‘Mr. Secretary, I reckon you’ll have to execute the order.’ Stanton snapped: ‘Mr. President, I cannot do it. The order is an improper one, and I cannot execute.’ Lincoln looked Stanton straight in the eye and said with determination: ‘Mr. Secretary, it will have to be done.'” Having done that, the President later admitted he had been in the wrong in a letter to General Ulysses S. Grant and took full responsibility for his action. As usual, Mr. Lincoln had to take more factors into consideration than did his subordinates.7

Often, however, President Lincoln did yield to Secretary Stanton, as when he refused to make an appointment desired by Congressmen George Julian and Owen Lovejoy. Mr. Lincoln told them: “Gentlemen, it is my duty to submit. I cannot add to Mr. Stanton’s troubles. His position is one of the most difficult in the world. Thousands in the army blame him because they are not promoted and other thousands out of the army blame him because they are not appointed. The pressure upon him is immeasurable and unending. He is the rock on the beach of our national ocean against which the breakers dash and roar, dash and roar without ceasing. He fights back the angry waters and prevents them from undermining and overwhelming the land. Gentlemen, I do not see how he survives, why he is not crushed and torn to pieces. Without him I should be destroyed. He performs his task superhumanly. Now do not mind this matter, for Mr. Stanton is right and I cannot wrongly interfere with him.”8

The relationship between Stanton and President Lincoln was indicated in a story told by presidential aide William O. Stoddard who was waiting to see Stanton in his office when Stanton received a telegram from the Shenandoah Valley which General Philip Sheridan announced his defeat of Jubal Early. Stanton. Shouting “this is the turning point, sir; the turning point!’, Stanton “rushed out into the crowded ante-room and hall, shouting the news with all the enthusiasm of a newsboy.” When Stanton recovered his decorum, he gave the telegram to Stoddard, ordering, “Take that to His Excellency! That’s news enough for one day. No more work after that.”9

President Lincoln was vulnerable on these short walks – to petitioners, to his own thoughts, and possible physical harm. Friend Henry Clay Whitney wrote that he knew “of his sitting down on the curbing of the walk between the Executive Mansion and the war department to write a note on his knees for immediate delivery.”9 The walks were frequent because all army telegraph dispatches were handled in an office next to Secretary Stanton’s. President Lincoln came there to get the latest information and sometimes just to get await from the pressures of the White House.

The 1864 Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City reported that “the building in which the business connected with the Department of War is transacted, is situated in the northwest corner of the grounds partly occupied by the White House, and is a building somewhat similar to that occupied by the State Department. Like the latter, it was originally only two stories high, but the great increase of business during the civil war necessitated the addition of another story. The dimensions of the building are 130 feet long by 60 wide. Like the State Department, this building also has a portico of the Ionic order, facing north. Its interior arrangement is similar to that of the State Department building.” According to the guidebook, “Here is transacted all business connected with Army operations. The accumulation of business, consequent upon the war, has caused a great increase of the clerical force over what it was in former years, when but a few thousand men constituted the Federal army. The floors of the rooms in the building are nicely carpeted, and the walls are decorated with pictures representing battle scenes.”10

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 36.

- Peter Cozzens, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, pp. 115-116

- Fletcher Pratt, Stanton: Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 143.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, pp. 34-35.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, “Lincoln’s Humor” and Other Essays of Benjamin Thomas, p.195.

- Frank A. Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 345.

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 387.

- Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, pp. 369-370.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 194 (from William Stoddard, White House Sketches, No. 12.”).

- Henry Clay Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln,, pp. 126-127.

- T. Loftin Snell, The Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City, pp. 31-32.

Visit

Noah Brooks

Simon Cameron

Edwin M. Stanton

Henry W. Halleck

Charles A. Dana

John Hay

Mr. Lincoln’s Office: Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief

Edwin M. Stanton (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)