Artist Francis B. Carpenter said that Abraham Lincoln referred to his office in the White House as the “shop.”1 Illinois attorney Henry Clay Whitney observed that for President “Lincoln the stately mansion was a mere workshop for the performance of dreary, routine labor.”2 Whitney wrote that Lincoln, who had once run and owned a country store, “eschewed all diplomatic or stately terms; could not be induced to speak of his house as the Executive Mansion, but termed it ‘this place,’ or of his room at the Capitol as the ‘President’s’ room; he disliked exceedingly to be called ‘Mr. President,’ and he requested persons with whom he was quite familiar and saw often to call him plain ‘Lincoln;’ he always spoke of the war as ‘this great trouble.’”3

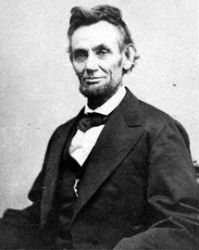

The commander-in-chief presided over his 31-room establishment without pretense. Cordelia Harvey, a soldier advocate from Wisconsin, described her first meeting with Mr. Lincoln at the White House: “He was alone, in a medium sized office-like room, no elegance about him, no elegance in him. He was plainly clad in a suit of black that illy fitted him. No fault of his tailor, however; such a figure could not be fitted. He was tall and lean, and as he sat in a folded up sort of way in a deep arm chair, one would almost have thought him deformed. At his side stood a high writing desk and table combined; plain straw matting covered the floor; a few stuffed chairs and sofa covered with green worsted completed the furniture of the presence chamber of the president of the great republic. When I first saw him his head was bent forward, chin resting on his breast, and in his hand a letter which I had just sent to him.”4

Ornithologist A. M. Ross recalled bringing President Lincoln a packet of “rebel” letters near midnight. The President reviewed the contents of the mail, which Ross had gathered as an undercover agent in Canada. “Having finished reading the letters, I rose to go, saying that I would go to Willard’s [Hotel], and have a rest. ‘No, no,’ said the President, ‘it is now three o’clock, you shall stay with me while you are in town; I’ll find you a bed;’ and leading the way, he took me into a bedroom, saying: ‘Take a good sleep; you shall not be disturbed.’ Bidding me ‘goodnight,’ he left the room to go back and pore over the rebel letters until daylight, as he afterwards told me. I did not awake from my sleep until eleven o’clock in the forenoon, soon after which Mr. Lincoln came into my room, and laughingly said: ‘When you are ready, I’ll pilot you down to breakfast,’ which he did…”5 Studying such papers, cables and correspondence occupied much of President Lincoln’s time. But his intelligence-gathering took many other forms, according to witnesses.

Wisconsin Republican Carl Schurz, who served as both a diplomat and general during the Civil War, wrote in his memoirs: “Those who visited the White House – and the White House appeared to be open to whosoever wished to enter – saw there a man of unconventional manners, who, without the slightest effort to put on dignity, treated all men alike, much like old neighbors; whose speech had not seldom a rustic flavor about it; who always seemed to have time for a homely talk and never to be in a hurry to press business, and who occasionally spoke about important affairs of State with the same nonchalance – I might almost say, irreverence – with which he might have discussed an every-day law case in his office at Springfield, Illinois. People were puzzled. Some interesting stores circulated about Lincoln’s wit, his quaint sayings, and also about his kindness of heart and the sympathetic loveliness of his character; but, as to his qualities as a statesman, serious people who did not intimately know him were inclined to reserve their judgment.”6

Mr. Lincoln was serious about his country but showed little concern for the state of his residence. Lincoln aide John Hay recalled the final meeting at the U.S. Capitol between outgoing President James Buchanan and incoming President Abraham Lincoln. It took place just before Mr. Lincoln’s First Inauguration in March 1861: “The courteous old gentleman took the new President aside for some parting words into the corner where I was standing. I waited with boyish wonder and credulity to see what momentous counsels were to come from that gray and weatherbeaten head. Every word must have its value at such an instant. The [soon-to-be] ex-President said: “I think you will find the water of the right-hand well at the White-House better than that at the left,’ and went on with many intimate details of the kitchen and pantry. Lincoln listened with that weary, introverted look of his, not answering, and the next day, when I recalled the conversation, admitted he had not heard a word of it.”7

The presidential office on the second floor of the White House was not fancy or well-furnished, but Mr. Lincoln fully understood its importance to the nation. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote: “After one Cabinet meeting in March [1865] young Fred Seward heard Postmaster General [William] Dennison say of the little old leather-covered chair at Lincoln’s desk, ‘I should think the Presidential chair of the United States might be a better piece of furniture than that.’ Lincoln turned, let his eyes scan the worn, torn, battered leather, and [said:] ‘You think that’s not a good chair, Governor,’ and with a half-quizzical, half-meditative look at it: ‘There are a great many people that want to sit in it, though, I’m sure I’ve often wished some of them had it instead of me!’”8

Twice a week, President Lincoln met with the Cabinet in his office. They were an ambitious, competitive group whose jealousies of each other and the President were often evident. Attorney General Edward “Bates’s Diary is full of entries which show how closely the cabinet members were watching each other,” wrote Helen Nicolay, daughter of presidential assistant John G. Nicolay. Bates “recorded a rumor, brought him by a great lover of gossip, that the Secretary of the Interior was in danger of being indicted for bribery. ‘One charge is that he took $400 from a person appointed to a 2d. class clerkship – salary $1400 per an[num]: I cannot believe this of Mr. Smith…’ At times he took a very dim view of the morals of the whole administration. On one such occasion he wrote:

Each one, statesman or General, is secretly working, either to advance his ambition, or to secure something to retire upon…There is now no mutual confidence among the members of the Govt. – and really no such thing as a C.[abinet] C.[ouncil]. The more ambitious members, who seek to control – Seward – Chase – Stanton – never start their projects in C.[abinet] C.[ouncil] but try first to commit the Prest., and then, if possible, secure the apparent consent of the members. Often, the doubtful measure is put into operation before the majority of us know that is proposed.”9

Occasionally, the jealousy among Lincoln’s subordinates boiled over into a crisis – as it did in December 1862. Complaints to members of Congress by Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase led to several tense visits from a Senate delegation seeking changes in the Cabinet. Shrewdly, he President obtained the resignations of both Chase and Secretary of State William H. Seward, but rejected both and maintained control of Cabinet. Chase, however, continued to be a thorn on his side and submitted multiple resignations. Finally in late June 1864, President Lincoln accepted Chase’s letter of resignation and decided to appoint Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden as his replacement. The pressure from political and commercial interests on the reluctant Fessenden to accept the Cabinet post became overwhelming. On July 3, “Secretary” Fessenden wrote to a cousin about how President Lincoln manipulated the situation:

The day before yesterday was one of the most miserable of my life. The President insisted upon appointing me Secretary of the Treasury against my consent and positive refusal to accept it. He cooly told me that the country required the sacrifice, and I must take the responsibility. On reaching the Senate, being a little late, I found the nomination sent in and confirmed. I went at once to my room, and commenced writing a letter declining to accept the office, but, though, I stayed there until after 5 P.M., I found no opportunity to finish it – being overrun with people, members and delegations appealing to me to “save the country.” Telegrams came pouring in from all quarters to the same effect, with messages from the President. About ten o’clock I had been able to finish my letter, and went to deliver it in person, but the President was in bed asleep. I left a message for him, and called again in the morning. He then refused to accept any letter declining the appointment, saying that Providence had pointed out the man for the crisis, none other could be found, and I had no right to decline. All this I could and should have withstood, but the indications and appearance from all quarters that my refusal would produce a disastrous effect upon public credit, already tottering, and thus perhaps paralyze us at the most critical juncture in our affairs, was too much for me. I felt much as Stanton said, “You can no more refuse than your son could have refused to attack Monett’s Bluff, and you cannot look him in the face if you do.” I told him it would kill me, and he replied, “Very well, you cannot die better than in trying to save your country.”10

In his office, Lincoln frequently greeted such important guests from Congress, military officers from the field, and humble visitors from the hinterlands. Lincoln aide William O Stoddard noted that the presidential office “was a remarkably silent workshop, considering how much was going on there. The very air seemed heavy with the pressure of the times, centering toward that place. There was only now and then a day bright enough to send any great amount of sunshine into the house, especially upstairs. It was not so much that coming events cast their shadows before, although they may have done so, as that the shadows, the ghosts, if you will, of all sorts of events, past, present and to come, trooped in and flitted around the halls and lurked in the corners of the rooms. The greater part of them came over from the War Office, westward, in company with messengers carrying telegraphic dispatches. Troops of them used to follow [Secretary of War Edwin M.] Stanton or [General Henry W.] Halleck right into Lincoln’s rooms. Seward too, was sometimes a gloomy messenger; but he was always diplomatically cheerful about it, and nobody could tell by his face but what he was bringing good news. The President could receive any kind of tidings with less variation of face or manner than any other man, and there was a reason for it. He never seemed to hear anything with reference to itself, but solely with a quick forward grasping for the consequences, for what must be done next.”11

The dignity of the nation’s 16th President sometimes escaped those who judged him by first appearances. The office he occupied did not change the character of the Springfield lawyer who occupied it. New York Times Editor Henry J. Raymond, himself a top Republican national official, observed: “Nothing was more marked in Mr. Lincoln’s personal demeanor than its utter unconsciousness of his position. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to find another man who would not, upon a sudden transfer from the obscurity of private life in a country town to the dignities and duties of the Presidency, feel it incumbent upon him to assume something of the manner and tone befitting that position. Mr. Lincoln never seemed to be aware that his place or his business were essentially different from those in which he had always been engaged. He brought to every question, – the loftiest and most imposing, – the same patient inquiry into details, the same eager longing to know and do exactly what was just and right, and the same working-day, plodding, laborious devotion, which characterized his management of a client’s case at his law office in Springfield. He had duties to perform in both places – in the one case to his country, as to his client in the other. But all duties were alike to him. All called equally upon him for the best service of his mind and heart, and all were alike performed with a conscientious, single-hearted devotion that knew no distinction, but was absolute and perfect in every case.”12

Mr. Lincoln shunned ostentation. “His habits at the White House were as simple as they were at his old home in Illinois,” wrote early biographer Josiah G. Holland. “He never alluded to himself as ‘President,’ or as occupying ‘the Presidency.’ His office, he always designated as ‘this place. ‘Call me Lincoln,’ said he to a friend, – ‘Mr. President’ had become so very tiresome to him. ‘If you see a newsboy down the street, send him up this way,’ said he to a [passerby], as he stood waiting for the morning news at his gate. Friends cautioned him against exposing himself so openly in the midst of enemies; but he never heeded them. He frequently walked the streets at night, entirely unprotected; and he felt any check upon his free movements as a great annoyance. He delighted to see familiar western friends; and he gave them always a cordial welcome.”13

President Lincoln perceived the burdens of the office he occupied. In a eulogy of President Zachary Taylor in 1850, Mr. Lincoln had said: “The Presidency, even to the most experienced politicians, is no bed of roses.”14 For President Lincoln, the nation’s capital would be a bramble of thorns. When he was elected in 1860, Washington had been a sleepy southern city with 61,122 residents – a quarter of them black. But Washington was changing as the president-elect arrived there in late February 1861. The southern senators and representatives who had dominated the national government in the 1850s returned home to states that had recently seceded from the Union. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “As the senators from the seceded states packed up their belongings to return to their hometowns, it was clear that a ‘regime had ended in Washington.’ The mansions of the old Southern aristocracy were closed; the clothes, papers, china, rugs, and furniture that embellished their lives were stowed in heavy trunks and crates to be conveyed by steamers to their Southern plantations.” Slaves, who constituted a relatively small percentage of Washington’s population, departed with their owners.15

The city’s transformation accelerated as President-elect Lincoln left Springfield on February 11 for a twelve-day trip to the capital. Washington chronicler Constance McLaughlin Green wrote: “Before the end of February, the air in Washington had cleared slightly…the resignation and departure of officials unwilling longer to serve the federal government lessened the tensions of earlier weeks when southern senators were making farewell speeches and representatives from the cotton states were hurrying home to share in the forming of the Confederacy.” The arrival of President-elect Lincoln also quieted the city. Green wrote: “Here was no fire-eater. The newspapers remarked with gratification upon his friendly greeting to the mayors and councils of Washington and Georgetown when they called upon him at his lodgings.”16

Nevertheless, the character of the city and citizens remained resolutely pro-southern. William O. Stoddard later wrote: “Socially, in the spring of 1861, Washington was ‘secesh’ to the back bone. The working men, and a portion of the ‘trades people’ – as the proud F.F.V.’s [members of the First Families of Virginia] called them – were ‘Union,’ and raised three thousand men for the army; but the rich men, the bankers, – except the loyal firm of L. Johnson & Co., half of Riggs & Co., and some others, – the old social leaders, including many who afterwards served the Government for their bread and butter, were bitterly disloyal. They seemed to have an insane idea that all the gentlemen and ladies were for the rebellion, and that it was decidedly low to come out for the Union and the Stars and Stripes.”17

Mr. Lincoln, ever prudent, was determined to try to preserve the loyalty of the border states during this period just as he tried to reconcile hostile Washington residents to his administration. The outbreak of hostilities at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 ended hopes of retaining Border States like Virginia, thus intensifying the need to preserve the loyalty of states like Missouri, Maryland and Lincoln’s own native Kentucky. Men like Kentucky Senator John Breckinridge, whom Mr. Lincoln had defeated for the Presidency, lingered in the city. Only later in the summer would Breckinridge desert the capital for the Confederacy. Pennsylvania journalist Alexander K. McClure wrote: “Washington at that time consisted of two entirely different communities, divided by official and social lines. Georgetown, which is now simply a pretty suburb of our great capital, was then the centre of culture, refinement and social exclusiveness. It had welcomed the earlier Presidents who came with the bluest blood of Virginia to grace official circles, but when the corncob pipe and the stone jug came with Jackson an impassable chasm was made between the social and the political circles of the capital. They were somewhat mingled under Van Buren and Tyler and Polk and Taylor, but when the ungainly form of the rail splitter came to the White House, alien to the aristocratic circles of Georgetown alike by birth and conviction, the social rulers of the capital paid little tribute to the political powers beyond playing the part of spy to give prompt information to the enemies of the Republic of the movements of the Government.”18

Lincoln aide Stoddard was himself a recent arrival from Illinois. In June 1861, he wrote: “Washington society is very much cut up into cliques – diplomatic, political, naval, military, west-end, navy yard, hotel, Congressional, Senatorial, &c., and sometimes the rivalry runs high. However, an officer of the army or navy, a department-man of good standing, a Senator or Congressman, can always obtain admission almost anywhere, if his character as a gentleman will warrant it.”19 By June, the Civil War had poured new blood into the city. Stoddard wrote: “Washington is a lively and prosperous town at present. Large sums of money are unavoidably spent here, the markets are busier than ever before, the hotels are full, and almost every department of trade is beginning to awake from the stagnation which overwhelmed us a few weeks ago.”20

Mary Todd Lincoln did not fit into this stratified society. Though well-born in Kentucky, Mrs. Lincoln was effectively frozen out by the southern sympathizers who ruled the top rung of Washington society. “Only two or three ladies were in the drawing room,” when English journalist William H. Russell visited the Executive Mansion in March 1861. “The Washington ladies have not yet made up their minds that Mrs. Lincoln is the fashion.”21 The social divide created by the Civil War was never breached during the Lincoln Administration. Writing of the White House reception on New Year’s Day, 1862, American journalist Ben Perley Poore noted: “Washington ‘society’ refused to be comforted. Those within its charmed circle would not visit the White House nor have any intercourse with the members of the administration.”22

Washington was a city under siege although no Confederate soldiers threatened its environs. The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in 1861 changed the city in many ways. It invigorated Union loyalists in the capital – but geographically, Washington was cut off the city from loyalists in the North who were needed to defend it. For days, Washington was a lonely semi-Union island surrounded by a sea of Confederate sympathizers in Virginia, Maryland and the city itself. A militia organized by Kansas Senator James Lane occupied the White House. On April 18, Lincoln secretary John G. Nicolay, who lived at the White House, wrote a brief memo: “Mails suspended. The telegraph cut. Lane’s improvised Frontier Guards perform squad drill in the East Room and bivouac on the velvet carpet among stacks of new muskets and freshly opened ammunition boxes.”23 On April 20, Nicolay wrote that detective Allan “Pinkerton was first man to get through the rebel lines during first blockade of Washington – came up to the White House and into the Cabinet room – took off his coat and ripping open the lining of his vest took about a dozen or more letters which he had thus brought to the President from the north.”24 Washingtonians were worried and the President was, troubled.

Lincoln scholar William Lee Miller wrote: “Washington in those April days had something of the aspect of threatened and besieged cities in the fearsome conflicts of other years and other places: families packing belongings, women and children being sent to safer places; prices for essential goods skyrocketing; theaters closing.”25 The President was highly distressed by the failure of northern soldiers to relieve the capital. When troops from Massachusetts traveled through Baltimore to relieve the capital, they were attacked by a pro-Confederate mob. “This morning the city is again alive with excitement. That infamous sheet the Baltimore Sun contains a most one-sided and exaggerated account of the riot there, charging the whole fault upon the soldiers and declares that the best blood of Maryland has been spilled by Northern mercenaries,” wrote Treasury official Lucius Chittenden in his journal on April 20. “It is certain this morning that all railroad communications with the north is cut off. Several bridges have been burned making all the routes impassable. The steam ferry boat at Havre de Grace has been scuttled and sunk, and Washington seems to be isolated…The Treasury Building has now about 200 soldiers quartered in it, and the sound of the bugle is heard almost hourly sounding through its corridors. Every avenue to the city is guarded and this wears ths aspects of a besieged town.”26 The President’s despair was reflected in comments in made to some Massachusetts soldiers who had been wounded at Baltimore: “”I don’t believe there is any North. The [New York] Seventh Regiment is a myth. Rhode Island is not known in our geography any longer. You are the only Northern realities.”27 The next day, April 25, the New York Seventh Regiment arrived. “Its parade up Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, behind a very good band, was one of the important incidents in the city’s life. On the preceding Sunday night the Washington telegraph instruments had stopped their clicking, with the wires cut,” wrote historian Kenneth Williams. “The capital was reassured, and reopened wires informed the country and dispelled alarm.”28

While Mr. Lincoln formulated plans to confront the rebellion, Mrs. Lincoln fumed and feuded. She was the victim of vicious rumors about her political sympathies: “I was agreeably disappointed in Mrs. Lincoln, as the ‘secesh’ ladies in Washington had been amusing themselves by anecdotes which could scarcely have been founded on facts,” wrote English journalist Russell. The Massachusetts congressman who would become the American minister to England, Charles Francis Adams, observed the vilification of Mrs. Lincoln in the drawing rooms of Washington that spring: “All manner of stories about her were flying around. She wanted to do the right thing but, not knowing how, was too weak and proud to ask. Servants are leaving because they must live with gentlefolks.”29

Mary’s cousin, Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, had accompanied Mary to Washington and she stayed at the White House for six months. Mrs. Grimsley later described the changes in Washington society: “The process of disintegration went on rapidly, and in a few weeks there was a thorough change socially. By degrees we ceased to meet at our informal receptions the Maryland and Virginia families who had always held sway, and dominated Washington society. Easy, suave, charming in manner, descended from a long line of aristocratic families, accustomed to wealth and all the amenities of social life, and etiquette, they resented the introduction of these new elements, and withdrew, to go into the Confederacy, where all their sympathies centered.” She wrote: “These were, in time, replaced by members of cultivated, refined, intellectual and wealthy people from the Northern cities, and officers of the army and navy with their wives, these, with several ladies of the delegation, notably Russian and Chilian [sic], with our many western friends, gave a new life to home parties.30

The first year in Washington was a time of personal and political trials for the Lincolns. Elmer E. Ellsworth, a young Lincoln friend from Illinois, was shot dead while helped retake Alexandria from the rebels in April 1861. In October, an old Lincoln friend, Oregon Senator Edward D. Baker, died in the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. Then in February 1862, the Lincolns’ beloved son Willie died – probably of typhoid. Of the three sons who had accompanied their parents to Washington, Willie was the most like the President. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “He was an avid reader, a budding writer, and generally sweet-tempered, all reminiscent of his father.”31 Young Willie’s seriousness was manifest. Elizabeth Todd Grimsley wrote of the Lincoln family’s first weekend in the White House: “That Sabbath, after lunch, Willie sat down at the piano in the Red room, where there were quite a number of persons, and began strumming some popular air; when opportunity came I said to him, ‘No one is without example, and as your father’s son, I would remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy’. ‘I will’ was the answer, and he faithfully kept his word, never even joining the family in their afternoon drives, when he found I preferred remaining at home.”32 The President loved romping with his rambunctious sons. Friend Ward Hill Lamon recalled Lincoln’s “ joyous companionship with his children suffered no abatement when he became a resident of the White House and took upon himself the perplexing cares of his great office. To find relief from those cares he would call his boys to some quiet part of the house, throw himself at full length upon the floor, and abandon himself to their fun and frolic as merrily as if he had been of their own age.”33

After Willie’s death, Nurse Rebecca Pomroy was recruited to help Mrs. Lincoln and young Tad Lincoln, who had fallen ill to the same illness as his brother. Pomroy biographer Anna Boyden wrote: “The President asked Miss [Dorothea] Dix if she could recommend to him a good nurse. She told him there was one out of her corps of nurses that she thought would give him perfect satisfaction. On inquiry, she told him it was Mrs. Pomroy. ‘Oh, yes,’ he said, ‘I have heard of her; will you get her for me?’”34 Although both the physician in charge of Pomroy’s hospital and Pomroy herself objected, Dix, who managed all army nurses, insisted and ordered Pomroy to the White House. Both Pomroy and her soldier patients were upset. “Oh, if I could only have staid with my boys!” she said to Dix, who replied: “Dear child, you don’t know what the Lord has in store for you. Others can look after your boys, but I have chosen you out of two hundred and fifty nurses to make yourself useful to the head of the nation. What a privilege is yours!”35 Boyden described Pomroy’s first day:

On their arrival they visited the Green Room, where Willie’s remains lay in state, and then passed on to the President’s chamber, where Mrs. Lincoln was lying sick, the President sitting beside her. He gave her a warm grasp of the hand, and said, ‘I am heartily glad to see you, and feel that you can comfort us and the poor sick boy.’ She was soon taken to the sick room of little Tad, introduced to the two physicians who sat in the hall just outside his door, who before leaving gave directions regarding medicine and treatment for every half-hour in the night.

At half past six the President came in and invited her down to dine with him; but she kept her station by the bedside of the little sufferer, who lay tossing with typhoid, and at intervals weeping for his dear brother Willie, “who would never speak to him any more.” The President came in about ten o’clock, sat down on the opposite side of the bed, and commenced inquiries. “Are you Miss or Mrs.? What of your family?”

She says, “I told him I had a husband and two children in the other world, and a son on the battle-field.” “What is your age? What prompted you to come so far to look after these poor boys?” She told him of her nineteen years’ education in the school of affliction, and that after her loved ones had been laid away, and the battle-cry had been sounded, nothing remained but for her to go, so strong was her desire. ‘Did you always feel that you could say, ‘Thy will be done?’”

And here the father’s heart seemed agonized for a reply.

She said, “No; not at the first blow, nor at the second. It was months after my affliction that God met me when at a camp-meeting.”

Here he showed great interest, and, she says, “While I was telling him my history, and, above all, of God’s love and care for me through it all, he covered his face with his hands while the tears streamed through his fingers. Then he told me of his dear Willie’s sickness and death. In walking the room, he would say: “This is the hardest trial of my life. Why is it? Oh, why is it” I tried to comfort him by telling him there were thousands of prayers going up for him daily. He said, “I am glad of that.” Then he gave way to another outburst of grief.

“The next night he seated himself in the same position, and begged me to go over the same recital, leaving nothing out. He would question me upon special points to learn how I obtained my faith in God, and the secret of placing myself in the Divine hands. Again, on the third night, he made a similar request, showing the same degree of interest as at first.”36

Springfield lawyer Shelby M. Cullom recalled Willie’s funeral: “When the ceremony was about concluded and President Lincoln stood by the bier of his dead boy, with tear-drops, falling from his face, surrounded by Seward, Chase, Bates, and others, I thought I never beheld a nobler-looking man. He was at that time truly, as he appeared, a man of sorrow, acquainted with grief, possessing the power and responsibilities of a President of a great Nation, yet with quivering lips and face bedewed with tears, from personal sorrow.”37 Dr. Phineas Gurley, who conducted Willie’s funeral, said that Willie’s “sickness was an attack of fever threatening from the first and painfully productive of mental wandering and delirium. All that the tenderest parental care and watching and the most assiduous and skillful medical treatment could do was done, and though at times even in the last stages of the disease his symptoms were regarded as favorable and inspired a faint and wavering hope of his recovery, still the insidious malady pursued its course unchecked, and on Thursday last, at the hour of five in the afternoon, the golden bowl was broken and the emancipated spirit returned to the God who gave it. ”38

Dr. Gurley wrote: “Willie’s death was a great blow to Mr. Lincoln, coming as it did in the midst of the war, when his burdens seemed already greater than he could bear. The little boy was always interested in the war and used to go down to the White House stables and read the battle news to the employees and talk over the outcome. These men all loved him and thought for one of his years, he was most unusual. When he was dying he said to me, ‘Doctor Gurley, I have six one dollar gold pieces in my bank over there on the mantel. Please send them to the missionaries for me.’ After his death those six one dollar pieces were shown to my Sunday School and the scholars were informed of Willie’s request.”39

Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: “For weeks afterward, Lincoln set aside Thursdays and closed himself off from the usual visitors ‘for the indulgence of his grief.’”40 Thinking of Willie made Mr. Lincoln maudlin and melancholy. While posing for sculptor Vinnie Ream in 1863, Mr. Lincoln began to cry while looking at the window at the South Lawn of the White House. “I was thinking of Willie,” Mr. Lincoln explained.41 New York banker and Union officer LeGrand B. Cannon recalled a conversation with President Lincoln in which the President read selections from Shakespeare. “I noticed that he was deeply move[d], his voice trembled, laying the Book on the table, he said, did you ever dream of a lost friend & feel that you were haveing [sic] a direct communion with that friend & yet a consciousness that it was not a reality. My reply was, yes I think all may have had such an experience. He repleyed [sic] so do I dream of my Boy Willey. He was utterly overcome. His great frame shook & Bowing down on the table he wept as only such a man in the breaking down of a great sorrow could weep.”42 At the funeral, Rev. Phineas Gurley said: “The beloved youth whose death we now and here lament was a child of bright intelligence and of peculiar promise. He possessed many excellent qualities of mind and heart which greatly endeared him not only to the family circle but to all his youthful acquaintances and friends. His mind was active, he was inquisitive and conscientious; his disposition was amiable and affectionate. His impulses kind and generous; his words and manners were gentle and attractive. It is easy to see how a child thus endowed could, in the course of eleven years entwine himself around the hearts of those who knew him best; nor can we wonder that the grief of affectionate mother today is like that of Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they were not.”43

Mrs. Lincoln’s grief over Willie’s death was particularly protracted. She wore only black for a year of mourning. Laura Redden, a journalist who visited her at the Soldier’s Home in the summer of 1862, recalled: “She entered the room where I awaited her, evidently striving for some composure of manner; but, as I took the hand which she extended to me, she burst into a passion of tears and gave up all effort at self-control. For a moment my feeling of respect for the wife of the President was uppermost; then my sympathies for the bereaved mother got the better of conventionalities, and I put my arm around her and led her to a seat, saying everything I could think of to calm her; but she could neither think nor talk of anything but Willie.”44 Mary’s anxiety worried the President. Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote that Lincoln talked to Illinois Senator “Orville Hickman Browning about ‘his domestic troubles,’ and Browning heard him say ‘several times’ that ‘he was constantly under great apprehension lest his wife should do something which would bring him into disgrace.’”45 Her manipulations of the White House accounts probably contributed to her husband’s apprehension.

Willie’s brother Tad proceeded to enliven the White House and comfort his father. “For many years before Lincoln became President, there had been no children living in the White House,” wrote Lincoln friend Noah Brooks. James “Buchanan was unmarried, and [Franklin] Pierce was childless when he took up his residence in the Executive Mansion. Although the great house, of which a large part was surrendered to public uses and inspection, never could be made to assume an air of domesticity, the three boys of the Lincoln family did much to invest the historic building with a phase of human interest which it did not have before.”46

Tad’s curiosity compensated for his lack of formal education and inability to articulate his thoughts clearly. Brooks later wrote: “On an occasion of issuing a presidential proclamation for a national fast, Tad expressed some curiosity as to what a fastday could possibly be. The result of his investigations filled him with dismay. An absolute fasting for one whole day, such as he was told to expect, was dreadful. Accordingly he established a food depot under the seat of a coach in the carriage-house. To this he furtively conveyed savings from his table-rations and such bits of food as he could pick up about the larder of the White House. Nobody suspected what he was doing, until a servant, one day, while cleaning the carriage, lighted on this store of provision, much to the rage and consternation of the lad, who stood by watching the gradual approach of the man to his provision depot. The President related the incident with glee, and added, ‘If he grows to be a man, Tad will be what the women all dote on – a good provider.’”47

Tad “invaded Cabinet councils with his boyish griefs or tales of adventure, climbed in his father’s lap when the President was engaged with affairs of state, and doubtless diverted and soothed the troubled mind of the President, who loved his boy with a certain tenderness that was inexpressible,” recalled journalist Brooks. “It was Tad, the mercurial and irrepressible boy of the White House, on friendly terms with the great and the lowly, who gave to the executive mansion almost the only joyous note that echoed through its corridors and stately drawing rooms in those troublous times.”48 Tad’s literal interpretation of events and people – such as his negative feelings toward Copperheads – could lead to trouble. “I guess I must exercise my executive clemency a little and pardon you, my patriotic boy. You shall not be whipped for this offense. Go and explain your case to your mother as it now stands,” he told son Tad when he complained to the President that Mrs. Lincoln threatened to whip him for defacing his copper-toed shoes as a patriotic gesture.49

The Lincolns’ time in Washington was not generally happy or healthy. Mr. Lincoln contracted a case of variloid and his wife suffered debilitating migraines as well as a serious head injury in an 1863 carriage accident. The city was unhealthy for everyone – soldiers and civilians alike. Waste from humans, horses and other animals overwhelmed the city during the Civil War. One wife of a Union army officer wrote home that “all the slops from sleeping rooms were thrown either into the gutters or alley. Here there are no sewers, no cess pools or vaults for any purpose in the yards….I was never in such a place for smells.”50 Under those circumstances, the Washington Canal that ran behind the White House was a virtual cess pool. It probably had caused Willie Lincoln’s death. Stoddard wrote in the New York Examiner, “The city generally is pleasant, but unhealthy to a degree positively alarming to weak nerves. The number of kinds of fever, colds, sore throats, rheumatics, small pox, gun-shot wounds, and delirium tremens, outside as well as inside the numerous hospitals, is enough to convince any man that ‘there is something wrong about the air of the place.’”51 Stoddard wrote:

We are not above tide-water here, and there is no current to speak of at high tide, while at low tide the flats are bared for wide reaches. One of those flats begins on the Mall, down there, at the line of shrubbery, and its other border is in the middle of the river. They selected the site for the Washington Monument upon that very gentle slope, because it was a better place for an ideal graveyard than it could ever become for the residences of the living. Upon the part of that flat which is under water, the Potomac continually deposits such material as any decent river might wish to be relieved of, and in course of time an ooze has been developed which can testify its peculiar qualities to the best advantage when the river is low and the tide is out, and there is a gentle, balmy south wind blowing. Then, sometimes you do not imagine that some careless person has left open the door of the conservatory. Everybody who spends much time in the White House is certain to suffer more or less. To be sure, the President has had only the smallpox, but he was well seasoned before he came, and he is too full of anxiety, all the while, for a different kind of fever to get into him. Mrs. Lincoln has suffered in ways which have no chronicle, and little Tad has undoubtedly been injured so that his constitution will not recover. Willie Wallace Lincoln died of it. The private secretaries were all tough, healthy fellows, pretty well seasoned, but they have had sharp down-turns to wrestle with.”52

Washington was indeed a city of political and visual contrasts. Ohio Congressman Albert Riddle said Washington was “as unattractive, straggling, sodden a town, wandering up and down the left bank of the yellow Potomac, as the fancy can sketch.”53 Lincoln scholar Herbert Mitgang wrote that “the city still had a rural appearance. In the summer there was dust, in the winter mud. Endless lines of quartermaster wagons churned the roads. The first horse-drawn street cars began to operate, running from the Navy Yard to Georgetown. Pennsylvania Avenue, destined to be the capital’s beautiful boulevard, was lined with rundown shacks; its cobbled pavement was broken and rutted. The contrasts were shocking. Negroes could be seen waiting outside the big hotels – Willard’s on Fourteenth Street, the Kirkwood on Twelfth, the National and Metropolitan on opposite sides of Sixth Street – to remind startled Northerners newly arrived that slaves were held in the capital. At Willard’s breakfast included pate de foie gras and fried oysters; the fifteen hundred underpaid government clerks, living in shabby rooming houses, ate more modestly.”54 Lincoln scholar Richard M. Lee noted that the number of clerks rose “from 1500 in 1861 to over 7000 in 1865…Even in good times clerks barely made ends meet; their families generally lived away from the expensive capital.”55

Pennsylvania Avenue was the only paved thoroughfare. Streets often became hazardous for travel. Historian Allan G. Bogue wrote: “When dry, the streets of Washington puffed dust at the pressure of the lightest foot or slowest turning wheel; when wet, they were quagmires. And when [congressional] sessions lingered into late spring or summer, the marshes and minor water courses all stank; household ‘slops’ putrefied in yard and street; privies became malodorous; and generations that knew no air conditioning steamed in high temperatures, oppressive humidity, and their own sweat. The wartime influx of humanity exacerbated conditions immeasurably as the problems of human waste and garbage disposal reached crisis proportions, and army slaughterhouses and makeshift hospitals added their unwholesome increment to the atmosphere.”56

The city had been built on the grand design of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, but the implementation in ensuing decades had not matched his design. “After sixty years, the inescapable conclusion was that much of the city remained unclear in principle, inchoate in design, unfinished in actuality,” wrote Jay Winik.57 Lincoln writer Jerrold M. Packard wrote: “From the top of the eighty-foot-high Jenkins Hill, on which the city’s designer had placed the legislative house, middle Pennsylvania Avenue traced a mile-long chain of hotels, cheap saloons, and whorehouses bordering the top end of the street, while more respectable shops and the relatively imposing Willard Hotel – the town’s best – continue westward. Just before the White House, the street reached the half-finished Treasury building, which, thanks to a whim on Andrew Jackson’s part, was built squarely where it would block the president’s view of the Capitol.”58 Ernest B. Furgurson noted that Washington’s “few monumental government buildings and broad avenues were far out of scale with its scattered brick townhouses, row of low-rise hotels and squalid slums of blacks and immigrants. Cattle, pigs and geese roamed free over broad empty stretches, including the acreage around the square stub of the Washington Monument, where indecision, vandalism and politics had halted construction at the 156-foot level.”59

Contemporary journalist William A. Croffut observed: “Few of the streets had any pretense of pavement. Some were paved with cobblestones so unstable as to be worse than none at all. On wet days Pennsylvania Avenue was a river of mud and filth in which cars and even light buggies were often mired so deep as to be extricated with great difficulty. The sidewalks were filled with Union soldiers on parole or absent without leave, and many of the houses concealed members of Confederate raider John Mosby’s guerillas acting as spies and waiting to dodge back across the river. There were forty-eight forts around the city and within the circumvallation [sic] were eighteen vast hospitals, sheltering thousands of sick and wounded.”60 The forts were not mere ornaments – they were needed when the city was threatened with a Confederate invasion in July 1864. President Lincoln himself watched the hostilities from the ramparts of Fort Stevens and was nearly killed by a sharpshooter.

As the war progressed, the city first became a vast encampment for the growing army and later a major medical center for Union casualties. The President and his wife frequently visited the wounded. Lincoln scholar Richard M. Lee noted: “When the sick and wounded of General [George B.] McClellan’s Peninsular battles arrived by the boatload the Sixth Street wharves in spring, 1862, the army had no choice but to commandeer hotels, churches, fraternal halls, schools and colleges, public buildings, private homes and even the insane asylum. In the wake of the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August, thousands more wounded and exhausted men were cast up on the city’s doorstep.”61

Washington was not prepared for this sudden upheaval. Croffut, who served in the army at the beginning of the war, wrote: “The city of Washington during the war was a desolation. The Capitol’s unfinished dome and wings looked like a Roman ruin. Secretary Seward and his clerks were cooped in a small and dingy brick building where the north end of the Treasury pushes its superb classic colonnade, and Secretary Stanton with his small department filled an insignificant building where now is the forelawn of the White House. Along the north edge of the Mall slowly crept and soaked through the city a fetid bayou called ‘The Canal,’ by courtesy, floating dead cats, and all kinds of putridity and reeking with pestilential odors. Cattle, swine, goats, sheep and geese ran at large everywhere. There were only two short sewers in the entire city and these were so choked as to backset the contents into cellars and stores on Pennsylvania Avenue. Happy hogs wallowed in the gutters. At night the city was in darkness, scarcely ameliorated by a faint glimmer on the remote corners, and the rustic lantern was by no means unknown.”62

Although slavery was abolished in the city in the spring of 1862, other vices flourished in the capital. Washington was not dull for those in search of mischief. In June 1863, journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “Washington is a lively, busy, and corrupt city. The painted women who flutter their shame upon the streets, the gambling dens which infest the principal avenues, the bribery and corruption which spreads its nets everywhere – all of these are the legitimate results of such a war as we now carry on. It is no argument against this or any other administration to say that such things exist here in greater aggravation than ever before. It is one of the evil fruits of a wicked war brought on by wicked men that such things should exist.”63

Despite the temptations and tensions of war, Washington was not always an exciting place – even for presidential aides. In 1863 Stoddard observed in one of his regular newspaper columns: ‘The humiliating confession must be made at all hazards – Washington, at least to the dwellers therein, is dull, insufferably dull. True, Congress is in session, and is doing very well, but it is not doing anything exciting. Even the expulsion of [Kentucky Senator] Garrett Davis, if he is to be expelled, would not excite anybody. The social parties are charming, and sufficiently numerous, but there is no excitement in them, except to a few unfledged young officers, in the glory of new uniforms. The weekly receptions at the President’s House are charming, and call together long lists of our most distinguished citizens, both soldiers and civilians; but a brilliant crowd does not make a man’s heart beat or his breath come quickly. No, everything is tame and dull.”64

For President Lincoln, life in Washington was seldom dull or routine. The pressures of the Presidency took a fearful toll on Mr. Lincoln physically and psychologically. On meeting Mr. Lincoln in his office in 1861, New York businessman and writer James R. Gilmore observed: “As he leaned back in his chair, he had an air of unstudied ease, a kind of careless dignity, that well became his station; and yet there was not a trace of self-consciousness about it him. He seemed altogether forgetful of himself and his position, and entirely engrossed in the subject that was under discussion. He had a large head, covered with coarse dark hair that was thrown carelessly back from a spacious forehead. His features also were large and prominent, the nose heavy and somewhat Roman, the cheeks thin and furrowed, the skin bronzed, the lips full, the mouth wide, but played about by a smile that was very winning. At my first glance he impressed me as a very homely man, for his features were ill-assorted and none of them was perfect, but this was before I had seen him smile, or met the glance of his deep set, dark gray eye – the deepest, saddest, and yet kindliest, eye I had ever seen in a human being.”65

Lincoln’s sad and haggard look deepened with the passage of time. Aide William Stoddard recalled working on correspondence in the White House late one night after the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. From Hay’s office across the hall from the President’s office, Stoddard –

“…saw men come out of Lincoln’s office and walk slowly away. I can recall Seward, Halleck, Stanton, but after they had departed I believed myself to be alone on that floor of the Executive Mansion except for the President in his room across the hall. It was then about nine o’clock for I looked at my watch. It seemed as if the rooms and hall were full of shadows, some of which came in and sat down by me to ask what I thought would become of the Union cause and the country. Not long afterward a dull, regularly repeated sound came out of Lincoln’s room through its half-open door. I listened, and became aware that this was the measured tread of the President’s feet, as he walked to and fro, up and down, on the farther side, beyond the Cabinet table, from wall to wall. He must have been listening to a great many weird utterances, as he walked and as he turned at the wall at either end of his ceaseless promenade.”

Ten o’clock came and found me still busy with my papers, but whenever I paused to endorse one of them I could hear the tread of the feet in that other room. The sound had become such a half-heard monotony that when, just at twelve o’clock midnight, it suddenly ceased, the silence startled me into listening. I did not come to go and look in upon him, but what a silence that was! It may have continued during many minutes. Then the silence was broken and the sound of the heavy feet began again. One o’clock came and I still had much work before me. At times Mr. Lincoln’s pace quickened as if under the spur of some burst of feeling.

Two o’clock came, for I again looked at my watch, and Lincoln was walking still. It was a vigil with God and with the future, and a long wrestle with disaster and, it may be, with himself – for he was weary of delays and sore with defeats. It was almost three o’clock when my own long task was done and I arose to go, but I did not so much as peer through the narrow opening of the President’s doorway. It would have been a kind of profanity. At the top of the stairway, however, I paused and listened before going down, and the last sound that I heard and that seemed to go out of the house with me was the sentry-like tread with which the President was marching on into the coming day.”66

Two months later in mid-July, the Lincolns oldest son Robert recalled visiting “my father’s office at the time in the afternoon at which he was accustomed to leave his office to go to the Soldiers Home, and found him in [much] distress, his head leaning upon the desk in front of him, and when he raised his head there were evidences of tears upon his face. Upon my asking the cause of his distress he told me that he had just received the information that Gen. Lee had succeeded in escaping across the Potomac river at Williamsport without serious molestation by Gen. Meade’s army.”67 Such military failures aged Lincoln prematurely.

Soldiers regularly marched past the White House and curious visitors marched past the President at semi-weekly receptions. Mr. Lincoln reviewed the troops and shook hands with the visitors. Lincoln aide John Hay wrote: “There was little gaiety in the Executive house during his time. It was an epoch, if not of gloom, at least of a seriousness too intense to leave room for much mirth. There were the usual formal entertainments, the traditional state dinners and receptions, conducted very much as they have been ever since. The great public receptions, with their vast rushing multitudes pouring past him to shake hands, he rather enjoyed; they were not a disagreeable task to him, and he seemed surprised when people commiserated him upon them. He would shake hands with thousands of people, seemingly unconscious of what he was doing, murmuring some monotonous salutation as they went by, his eye dim, his whole form grow attentive; he would greet the visitor with a hearty grasp and a ringing word and dismiss him with a cheery laugh that filled the Red Room with infectious good nature. Many people armed themselves with an appropriate speech to be delivered on these occasions, but unless it was compressed into the smallest possible space, it never got utterance; the crowd would jostle the peroration out of shape. If it were brief enough and hit the President’s fancy, it generally received a swift answer. One night an elderly gentleman from Buffalo said ‘Up our way, we believe in God and Abraham Lincoln,’ to which the President replied, shoving him along the line, ‘My friend, you are more than half right.’”68

Noah Brooks, an old Lincoln friend from Illinois, described a typical White House reception in January 1864:

“Of course, there is a great variety of costume at the evening affair, but most of the visitors go in party dress – the women rigged out in full fig, with laces, feathers, silks, and satins rare, leaving their bonnets in an anteroom; and the gentlemen appear in light kids and cravats got up in great agony by their hairdressers. Mixed in with these are the less airy people who wear somber colors and who dress in more quiet style. At the morning receptions ladies wear their walking dress, and the show is not half so fine as by gaslight when the glittering crowd pours through the drawing rooms into the great East Room, where they circulate in a revolving march to the music of Marine Band stationed in an adjoining room. The gentlemen deposit their hats and outside peeling in racks, provided with checks, and then join the procession which presses into the Crimson Drawing Room where it is met by the train of ladies which files from a retiring room. Uncle Abraham stands by the door which opens into the Blue Room, flanked by Marshal [Ward Hill] Lamon and his private secretary who introduce the new arrivals, each giving his name and that of the lady who accompanies him. The President shakes hands, says ‘How-do,’ and the visitor is passed on to where Mrs. Lincoln stands, flanked by another private secretary and B[enjamin] B. French, the Commissioner of Public Buildings, who introduce the party. Then all press on to the next room where they admire each other’s good clothes, criticize Mrs. Lincoln’s new gown, gossip a little, flirt a little, yawn, go home, and say, ‘What a bore!’ Such is our republican court, and the most bored man in it is Old Abe who hates white kid gloves and a crowd.”69

One night, some of the presidential bodyguard decided to attend a presidential levee. Sergeant Smith Stimmel recalled that “we stood in the anteroom for some time, watching the dignitaries pass in, before we could make up our minds to venture into the presence of the President. Cabinet Ministers, the Judges of the Supreme Court, Senators and Congressmen, Foreign Ambassadors in their dazzling uniforms, accompanied by their wives, army and navy officers of high rank, and the aristocracy of the city, all in full evening dress, were there. Naturally we boys in the garb of the common soldier, felt a little timid in the presence of such an assemblage.” However, “the door-keeper said ‘Go in, boys, he would rather see you boys than all the rest of these people.’ So we plucked up courage and went in. The President gave us a cordial shake of the hand. We bowed to Mrs. Lincoln and the others and passed on into the large East room with the rest of the guests. At first it was a little like taking a cold bath when the water is a little extra chilly, but the first douse took off the chill, and after that we felt quite at home.”70

Mary A. Livermore, wife of the editor of the Chicago-based New Covenant, visited the White House in early 1865 and reported on the evening reception: “We remained for some time, watching the crowds that surged through the spacious apartments, and the President’s reception of them. When they entered the room indifferently and gazed at him, as if he were a part of the furniture, or gave him simply a mechanical nod of the head, he allowed them to pass on, as they elected. But when he was met by a warm grasp of the hand, a look of genuine friendliness, the President’s look and manner answered the expression entirely. To the lowly and humble he was especially kind; his worn face took on a look of exquisite tenderness, as he shook hands with soldiers who carried an empty coat sleeve, or swung themselves on crutches; and not a child was allowed to pass him by without a kind word from him. A bright boy, about the size and age of the son he had buried, was going directly by without appearing even to see the President. ‘Stop, my little man’, said Mr. Lincoln, laying his hand on his shoulder, ‘aren’t you going to speak to me?’ And stooping down he took the child’s hands in his own, and looked lovingly in his face, chatting with him for some moments.”71

“Father Abraham” had a special fondness for children. Robert S. Brown, son of a White House staffer, admitted to the President that he was constantly hungry: “Well that’s a terrible state for a boy to be in. We’ll have to see about that!…Peter, I want you to feed this boy. He looks hungry and admits it. Fill his legs too; if he is like my boys, his legs are hollow.”72

The White House was political fish bowl for the First Family. Cabinet members, congressmen, Union officers and would-be officeholders gathered just outside their bedrooms on the second floor, hoping to see the President. Lincoln scholar Ronald D. Rietveld wrote: “The Lincolns worked out their household arrangements, following an arrangement which served presidential families from 1830 to 1902, when all second-floor offices were moved to Theodore Roosevelt’s remodeled West Wing. The eastern half of the White House, roughly speaking, was to be devoted to business and public affairs, while the western half, except for the state dining room, would serve the needs of the family. But the Lincolns had only one living room, the oval room above the Blue Room. It served as a library and parlor, ‘really a delightful retreat.’”73 To preserve a bit of privacy from the eyes of his visitors, the President had constructed a private passageway from his office to the Oval Room, which connected to the bedrooms used by Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln. Tad’s room was across the hall, but he often could be found in his father’s bed.

Elizabeth Grimsley recalled that the family’s initial “tour of observation [of the White House] was a disappointing one, as the only elegance of the house was concentrated on the East, Blue and Red rooms, while the family apartments were in a deplorably shabby condition as to furniture (which looked as if it had been brought in by the first President), although succeeding house-keepers had taxed their ingenuity and patience to make it presentable.”74 After she was criticized for taking government-owned furniture when she left the White House, Mrs. Lincoln defended herself to a friend in early 1866. She wrote about “that dilapidated mansion, we found on entering it. I never had it in my power, to order a chair, or a comfortable lounge, therefore, as a matter of course, had nothing to do with the pecuniary department. If the chais had been regalle [sic] & everything else to correspond, I trust conscientious scruples, would have prevented my appropriating, what did not belong to me. A very simple little dressing table so plain that no one would have given $20 for it. My husband said eighteen months before, he wished to have a memento of me as he often found me seated, with my hair being dressed before it. The Comm. [of Public Buildings] and Sec. of I[nterior]. both said we might have it & my husband said, he would give $40 for it, which was declined. This was the only article, I ever say, be it in all humility spoken, that I should have ever given houseroom, if they had been mine.”75 Mrs. Lincoln did use a $20,000 appropriation from Congress to upgrade the public areas of the White House but her overspending on the project embarrassed and infuriated her husband.

Lincoln aide Stoddard, who worked closely with Mrs. Lincoln, thought the White House shabby. “The first floor fronting on Pennsylvania avenue may be divided into three equal sections. The eastern third contains the Congressional and private dining-rooms, and adjacent apartments; the centre is made up of a respectable vestibule in front, where the hat and cloak racks are set up on reception nights, and in the rear of this are three moderate-sized parlors, known as the red room, the blue room or ‘oval,’ and the green room – the first of these being used by Mrs. Lincoln as a private parlor. The third section is the famous ‘East Room,’ gaudily and tastefully furnished, and unadorned with works of art, except at levees. The upper story of the eastern section is used by the family of the occupant; the library, really a delightful retreat, and several sleeping rooms, are in the centre; while all the space over the East Room is devoted to the business purposes of the Executive – his public reception room, council chamber and the offices of his various secretaries.”76

Work at the White House went on nearly every day of the year. John Hay described his boss’s routine: “The President rose early, as his sleep was light and capricious. In the summer, when he lived at the Soldiers’ Home, he would take his frugal breakfast and ride into town in time to be at his desk at eight o’clock. He began to receive visits nominally at ten o’clock, but long before that hour struck the doors were besieged by anxious crowds, through whom the people of importance, Senators and members of Congress, elbowed their way after the fashion which still survives. On days when the Cabinet met, Tuesdays and Fridays, the hour of noon closed the interviews of the morning. On other days it was the President’s custom, at about that hour, to order the doors to be opened and all who were waiting, to be admitted. The crowd would rush in, thronging the narrow room, and one by one, would make their wants known. Some came merely to shake hands, to wish him Godspeed; their errand was soon done. Others came asking help or mercy; they usually pressed forward, careless, in their pain, as to what ears should overhear their prayer. But there were many who lingered in the rear and leaned against the wall, hoping each to be the last, that they might in tete a tete unfold their schemes for their own advantage or their neighbor’s hurt. These were often disconcerted by the President’s loud and hearty, ‘Well, friend, what can I do for you?’ which compelled them to speak, or retire and wait [for] a more convenient season.”77

Like the nation’s third President, Thomas Jefferson, Mr. Lincoln was sometimes criticized for his informal attire in the Executive Mansion – especially his fondness for slippers. But presidential secretary John G. Nicolay defended him, writing “If a few instances occurred where visitors found him in a faded dressing-gown and with slippers down at the heel, such incidents were due, not to carelessness or neglect, but to the fact that they had thrust themselves upon him at unseasonable and unexpected hours. So also were some critics who, coming with the intention to find fault, could see nothing but awkwardness in his movements and wrinkles in his clothes. In the fifteen hundred days during which he occupied the White House, receiving daily visits at almost all hours, often from seven in the morning to midnight, from all classes and conditions of American citizens, as well as from many distinguished foreigners, there was never any eccentric or habitual incongruity of his garb with his station.”78

Given the hours of his work and the constant press of politics and petitioners, Mr. Lincoln’s occasional casual dress is understandable. Nicolay’s assistant, John Hay, wrote: “It would be hard to imagine a state of things less conducive to serious and effective work, yet in one way or another, the work was done. In the midst of a crowd of visitors who began to arrive early in the morning and who were put out, grumbling, by the servants who closed the doors at midnight, the President pursued those labors which will carry his name to distant ages. There was little order or system about it; those around him strove from beginning to end, to erect barriers to defend him against constant interruption, but the President himself was always the first to break them down. He disliked anything that kept people from him who wanted to see him, and although the continual contact with importunity which he could not satisfy, and distress which he could not always relieve, wore terribly upon him and made him an old man before his time, he would never take the necessary measures to defend himself.”79

President Lincoln himself tried to erect as few barriers to the public as possible. Biographer Richard J. Carwardine wrote: “In consequence of what Henry J. Raymond called Lincoln’s ‘utter unconsciousness of his position’, ordinary men and women regarded him more as a neighbor to be dropped in upon than as a remote head of state. ‘Mr. Lincoln is always approachable and this is greatly in his favor’, explained the Washington correspondent of the New York Independent. ‘The people can get at him and impress upon him their views without difficulty.’ Though his visitors included, in the words of one observer, ‘loiterers, contract-hunters, garrulous parents on paltry errands, toadies without measure, and talkers without conscience’, Lincoln was adamantly opposed to restricting access.”80

The President called such encounters his “public opinion baths.” When a Union officer suggested that visitors should be better screened and regulated, Lincoln replied:

“Ah, yes! Such things do very well for you military people, with your arbitrary rule, and in your camps. But the office of president is essentially a civil one, and the affair is very different. For myself, I feel, though the tax on my time is heavy, no hours of my day are better employed than those which thus bring me again within the direct contact and atmosphere of our whole people. Men moving only in an official circle are apt to become merely official, not to say arbitrary, in their ideas, and are apter and apter, with each passing day, to forget that they only hold power in a representative capacity. Now this is all wrong. I go into these promiscuous receptions of all who claim to have business with me twice each week, and every applicant for audience has to take his turn as if waiting to be shaved in a barber’s shop. Many of the matters brought to my notice are utterly frivolous, but others are of more or less importance, and all serve to renew in me a clearer and more vivid image of that great popular assemblage, out of which I sprang, and to which at the end of two years I must return. I tell you, Major, that I call these receptions my public-opinion baths; for I have but little time to read the papers and gather public opinion that way, and though they may not be pleasant in all their particulars, the effect as a whole is renovating and invigorating to my perceptions of responsibility and duty. It would never do for a president to have guards with drawn sabres at his door, as if he fancied he were, or were trying to be, or were assuming to be, an emperor.”81

The pace of presidential labors was killing. Aide Stoddard wrote:

“When the President lives in town he commences his day’s work long before the city is astir, and before breakfast he consumes two hours or more in writing, reading or studying up some of the host of subjects which he has on hand. It may be the Missouri question, the Maryland imbroglio. The [General William] Rosecrans removal question, or the best way to manage some great conflicting interest which engrosses his attention, but these two best hours of the fresh day are thus given to the work Breakfast over, by nine o’clock he has directed that the gate which lets in the people shall be opened upon him, and then the multitude of cards, notes and messages which are in the hands of his usher come in upon him. Of course, there can be no precedence, except so far as the President makes it; and, as a majority of the names sent in are new to him, it is very much of a lottery as to who shall get in first. The name being given to the usher by the President, that functionary shows in the gratified applicant, who may have been cooling his heels outside for five minutes or five days, but is now ushered into a large square room, furnished with green stuff, hung around with maps and plans, with a bad portrait of Jackson over the chimney piece, a writing table piled up with documents and papers, and two large, draperied windows looking out upon the broad Potomac, and commanding the Virginia Heights opposite, on which numberless military camps are whitening in the sun. The President sits at his table and kindly greets whoever comes. To the stranger he addresses his expect ‘Well’ and to the familiar acquaintance he says, ‘And how are you to-day, Mr. ——?’ though it must be confessed that he likes to call those whom he likes by their first names, and it is ”Andy’ (Curtin), ‘Dick’(Yates), and so on. [Secretary of State William H.] Seward he always calls ‘Governor,’ and Blair or Bates is ‘Judge;’ the rest are plain ‘Mister,’ never ‘Secretary.’ With admirable patience and kindness, Lincoln hears his applicant’s request, and at once says what he will do, though he usually asks several questions, generally losing more time than most business men will by trying to completely understand each case, however unimportant, which comes before him.”82

The atmosphere in Lincoln’s office was informal except when a stuffy visitor such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who prompted more formal decorum. Contrary to the image created by Francis B. Carpenter’s painting of the Emancipation Proclamation, noted Stoddard: “When that half-dozen of overworked and anxious men did get together, it was not their habit, dignified as they were, and however important their business, to collect in studied stiffness around the table; but several times when I have been called in – to be sent for papers, &c. – I have seen one stretched on the sofa with a cigar [in] his mouth, another with his heels on the table, another nursing his knee abstractedly, the President with his leg over the army of his chair, and not a man of them all in any wise sitting for his picture.”83

Despite the pressure of business in the White House, Mr. Lincoln usually enjoyed visits from old Illinois friends and the opportunity to reminisce about more peaceful days. Illinois Judge Anson S. Miller recalled: “I was in Washington three or four times during the war; and during every visit I saw Mr. Lincoln repeatedly. The first time I was a little anxious to know how he would receive me in the midst of his greatness. I sent in my card; but, without allowing me to wait, he came to the door himself, and said, in his old hearty way, ‘Come in.’ He was unspoiled by prosperity. He gave to his old friends a generous welcome, as informal as possible.”84 Springfield attorney Thomas Lewis recalled going to the White House one night in 1862 at “seven o’clock, hoping to find him at home, but to my surprise I found over half a dozen in the waiting room. The doorkeeper said I must await my turn. I gave him my card, with the request that he hand it to Mr. Lincoln, and I was soon ushered in. We shook hands. I told Mr. Lincoln that I was on my way to Memphis to practice law, and that I was there to make a short visit with him. He said: ‘You see the fix I am in. I am kept here every night until nine to twelve o’clock, and never know when I can leave. You go to Mary’s room and visit her until I come. It will be between nine and twelve o’clock. Then we will talk Springfield over.’ I was piloted to Mrs. Lincoln’s room. At eleven o’clock Mr. Lincoln came in.” When Lewis rose to leave at 2 A.M., President Lincoln insisted on giving him a letter of introduction to General Ulysses S. Grant.85

President Lincoln could write passes and pardons, but there were limits to the powers of his exalted office that he clearly understood. Army telegraph operator William B. Wilson remembered:

“One night the Washington Infirmary burned down, and, as customary after such a disaster, the next day brought the President the usual complement of offers for fire engineers and firemen. Philadelphia’s patriotism, true to its tradition, could not await the slow progress of the mail, but sent forward a committee of citizens to urge upon the President the acceptance of a fully equipped fire brigade for Washington. On their arrival at the White House they were duly ushered into the Executive Chamber and courteously and blandly received by Mr. Lincoln. Eloquently did they urged the cause of their mission, but valuable time was being wasted, and Mr Lincoln was forced to bring the conference to a close, which he did by interrupting one of the committee in the midst of a grand and to-be-clinching oratorical effort by gravely saying, and as if he had just awakened to the true import of the visit, ‘Ah! Yes, gentlemen, but it is a mistake to suppose I am at the head of the fire department of Washington. I am simply the President of the United States.’ The quiet irony had its proper effect, and the committee departed.”86

There were no limits, however, to President Lincoln’s devotion to Union soldiers. Artist Francis B. Carpenter “was always touched by the President’s manner of receiving the salute of the guard at the White House. Whenever he appeared in the portico, on his way to or from the War or Treasury Department, or on any excursion down the avenue, the first glimpse of him was, of course, the signal for the sentinel on duty to ‘present arms.’ This was always acknowledged by Mr. Lincoln with a peculiar bow and touch of the hat, no matter how many times it might occur in the course of a day; and it always seemed to me as much a compliment to the devotion of the soldiers, on his part, as it was the sign of duty and deference on the part of the guard.”87California reporter Noah Brooks observed: “Mr. Lincoln’s manner toward enlisted men, with whom he occasionally met and talked, was always delightful in its bonhomie and its absolute freedom from anything like condescension. Then, at least, the ‘common soldier’ was the equal of the chief magistrate of the nation.”88 The President was solicitous of their welfare. Soldiers visiting the White House usually found a receptive audience.

Not everyone else did. Brooks wrote:

“Almost everybody would like to be President, and there are but few persons who realize any of the difficulties which surround a just administration of the duties of the Executive office. The other day a delegation from Baltimore called upon the President by appointment to consider the case of a certain citizen of Baltimore whom it was proposed to appoint to a responsible office in that city. The delegation filed proudly in, formed a semi-circle in front of the President, and the spokesman stepped out and read a neat address to the effect that, while they had the most implicit faith in the honesty and patriotism of the President, etc., they were ready to affirm that the person proposed to be placed in office was a consummate rascal and notoriously in sympathy, in not in correspondence, with the rebels. The speaker concluded and stepped back, and the President replied by complimenting them on their appearance and professions of loyalty, but said he was at a loss what to do with ____, as a delegation twice as large, just as respectable in appearance and no less ardent in professions of loyalty, had called upon him four days before, ready to swear, every one of them, that ____ was one of the most honest and loyal men in Baltimore. ‘Now,’ said the President, we cannot afford to call a Court of inquiry in this case, and so, as a lawyer, I shall be obliged to decide that the weight of testimony, two to one, is in favor of the client’s loyalty, and as you do not offer even any attempt to prove the truth of your suspicions, I shall be compelled to ignore them for the present.’ The delegation bade the President good morning and left.’”89

Missourian Enos Clarke was more upbeat in his remembrance of a combative meeting President Lincoln held with 70 Missouri Radicals in late September 1863. The meeting started off badly in Clarke’s opinion but the cagey President drew out the delegation’s objections to his policies and managed them with dexterity. Mr. Lincoln had confidence in his own abilities to deal with his critics. Just before meeting with the truculent group, Mr. Lincoln told John Hay: “John, I think I understand this matter perfectly and I cannot do anything contrary to my convictions to please these men, earnest and powerful as they may be.”90 Clarke recalled: “Toward the close of the conference he went on to speak of his great office, of its burdens, of its responsibilities and duties. Among other things he said that in the administration of the government he wanted to be the president of the whole people and of no section. He thought we, possibly, failed to comprehend the enormous stress that rested upon him. ‘It is my ambition and desire,’ he said with considerable feeling, ‘to so administer the affairs of the government while I remain president that if at the end I shall have lost every other friend on earth I shall at least have one friend remaining and that one shall be down inside me.’”91