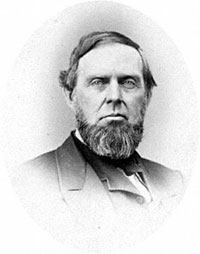

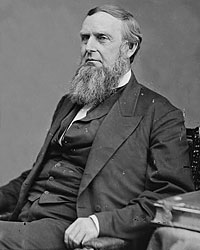

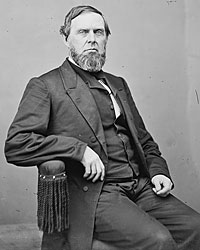

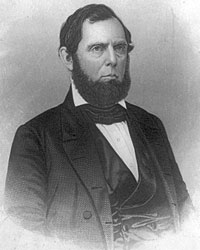

Senator from Iowa (Whig, Republican, 1856-65, 1867-73) who replaced John Usher as Secretary of the Interior in April 1865 and served until 1866 when differences with President Andrew Johnson prompted his resignation. Despite allegations of corruption in the Interior Department, Harlan was speedily returned to his old job in the Senate.

An attorney, sometime co-counsel to Abraham Lincoln, judge and university (Iowa Wesleyan) president, he was generally loyal to President Lincoln and headed the President’s campaign fund raising and the Republican congressional committee in 1864. The President’s Illinois friends had pushed the nomination of State Auditor Jesse K. Dubois and Orville H. Browning for the post, but President Lincoln was always sensitive to giving Illinois a second post in the cabinet. Harlan was a prominent Methodist and Mr. Lincoln told Congressman-elect Shelby M. Cullom, who came to the White House to lobby, that he had promised Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson to appoint Harlan: “The Methodist Church has been standing by me very generally. I agreed with Bishop Simpson to give Senator Harlan this place, and I must keep my agreement. I would like to take care of Uncle Jesse, but I do not see that I can as member of my cabinet.”1

General Grenville Dodge recalled how Senator Harlan intervened in one visit he made to the White House in the fall of 1864: “When I arrived at Washington and went to the White House to call on President Lincoln, I met Senator Harlan of my state in the ante-room and he took me in to see the President. It happened to be at the hour when the President was receiving the crowd in the ante-room next to his room. Senator Harlan took me up to him immediately and presented me to him. President Lincoln received me cordially and said he was very glad to see me. He asked me to sit down while he disposed of the crowd. I sat down and waited; I saw him take each person by the hand and in his kindly way dispose of them. To an outsider, it would seem that they all got what they wanted, for they seemed to go away happy. I sat there for some time, and felt that I was over-staying my time with him, so stepped up and said that I had merely called to pay my respects and that I had no business, so would say goodbye. President Lincoln turned to me and said, ‘If you have the time, I wish you would wait; I want to talk to you.” Eventually, Mr. Lincoln got around to reading General Dodge a chapter of a humorous book, serving him lunch and interrogating him about the prospects of the Army of the Potomac, then laying siege to Richmond.”2

The Harlans were often guests of Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln on their afternoon carriage rides. “During these drives to the country we had, of course, unrestrained conversation with each other,—very much, I think, as if we had been members of the same family,” Harlan recalled. “The last drive we had together occurred almost immediately after the fall of Richmond, and the surrender of the Confederate at Appomattox. On this occasion we four drove across the Potomac River, on Long Bridge into Virginia, and thence in the direction of Falls Church, through the country still marred and scarred—perhaps I ought to say devastated—by the recent presence of the great armies who had stripped it of almost every vestige of the environments of civilized life, including its once comfortable habitations, outbuildings, orchards, field fences, gardens and ornamental shrubbery. Even the hills had been deprived of their once majestic forests of native trees. After a long drive, occupying several hours, we returned to Washington to resume the drudgery of our respective official stations.”3

Senator Harlan said Mr. Lincoln’s demeanor was “transfigured. That indescribable sadness which had previously seemed to me an adamantine element of his very being had been suddenly changed for an equally indescribable expression of serene joy!—as if conscious that the great purpose of his life had been achieved. His countenance had become radiant,—emitting spiritual light something like a halo. Yet there was no manifestation of exaltation or ecstasy. He seemed the very personification of supreme satisfaction. His conversation was, of course, correspondingly exhilarating.”4

Harlan recalled a meeting with President Lincoln aboard the River Queen after he, his wife, Mrs. Lincoln and others had visited Richmond. He wrote that President Lincoln’s “whole appearance, pose and bearing had marvelously changed. He was, in fact, transfigured. That indescribable sadness which had previously seemed to be an adamantine element of his very being had been suddenly changed for an equally indescribable expression of serene joy, as if conscious that the great purpose of his life had been attained.”5

Mary Todd Lincoln abetted and encouraged a relationship between Senator Harlan’s daughter Mary and her son Robert. The two were married in 1868. President Lincoln had once told Secretary of War Edwin Stanton: “Mary is tremendously in love with Senator Harlan’s little daughter. I think she has picked her out for a daughter-in-law. As usual, I think Mary has shown fine taste.”6

Footnotes

- Reinhold H. Luthin, The Real Lincoln, pp. 556-557.

- Grenville M. Dodge, Personal Recollections of President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant and General William T. Sherman, pp. 19-20.

- Katherine Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 252-253.

- Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 253.

- Shelby Foote, The Civil War, Volume III, p. 903

- Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 274-275.

Visit

John Usher

Robert Todd Lincoln

Edwin Stanton

Reception Room

Abraham Lincoln and Iowa

James Harlan (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)