Commissioner of Public Buildings, Benjamin Brown French, succeeded William S. Wood in the fall of 1861. After his appointment French wrote in his diary on September 8: “I was at the President’s and saw Mrs. Lincoln and the President. Mrs. L. expressed her satisfaction at my appointment, and I hope and trust she and I shall get along quietly. I certainly shall do all in my power to oblige her and make her comfortable. She is evidently a smart, intelligent woman, and likes to have her own way pretty much. I was delighted with her independence and her lady-like reception of me. Afterwards I saw the President and he received me very cordially.”1

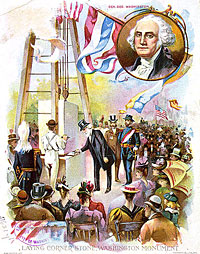

Once a Democrat, he was clerk of the House when Congressman Lincoln arrived in Washington in 1847; Lincoln’s vote helped defeat him for reelection. A prominent Washington Republican, he served as marshal of the first Lincoln Inaugural and as general factotum to the President’s aides in the early days of the Lincoln Administration. He worked hard to ingratiate himself with the Lincoln in order to get the public buildings post – even writing a long poem for Mrs. Lincoln. He was the deputy to Marshal Ward Hill Lamon at the dedication of the Gettysburg Battlefield for which he composed a funeral dirge that was sung at the ceremony. He also served the factotum who introduced Mrs. Lincoln at receptions in the Blue Room. “Every Saturday from 1 to 3 M. & every Tuesday from 1/2 past 8 to 1/2 past 10, I am required, as an official duty, to be at the President’s to introduce visitors to Mrs. Lincoln. It is a terrible bore, but, as a duty I must do it…”2 In 1865, he oversaw the White House preparations for President Lincoln’s funeral—including the design of the catafalque.

Perhaps French’s most important function was to oversee the expenditures for the White House redecorating. He had to find a way to pay the excess bills that had been accumulated under his predecessor, William S. Wood. On December 16, 1861, French recorded in his diary the events of the previous weekend: “Mrs. Lincoln sent down for me to go up and see her on urgent business. I could not go, of course, but sent word I would be up by 9 A.M. Saturday. Although suffering with a severe headache I went & had an interview with her, and with the President, in relation to the overrunning of the appropriation for furnishing the house, which was done, by the law, ‘under the President.’ The money was actually expended by Mrs. Lincoln, & she was in much tribulation, the President declaring he would not approve the bills overrunning the $20,000 appropriated. Mrs. L. wanted me to see him & endeavor to persuade him to give his approval to the bills, but not to let him know that I had seen her!”3

Although the President was infuriated by the overspending, French arranged a deficiency appropriation from Congress of $4500 and to shift funds from other Washington projects to cover Mrs. Lincoln’s spending spree. Historian Margaret Leech reported the scene:

On hearing of the outstanding bill, the President said that he would pay it himself, and in extremity Mrs. Lincoln sent for the Commissioner of Public Buildings, Major French. Since his appointment, he had ample opportunity to become acquainted with Mrs. Lincoln’s love of money, and spendthrift ways with it. The opening of the winter social season had, moreover, put him ‘on the most cosey terms’ with her because of his duty of presenting the visitors to the President’s wife at the White House receptions. French was a stout, choleric old gentleman. With his arrogant mouth and his bristling gray side whiskers, brushed to the front, he resembled a cartoon of a Victorian papa. He kept a weather eye on Mrs. Lincoln, and winced suspiciously when she flattered him; but he was very patient with the Republican Queen.

Mrs. Lincoln was not up when French arrived at the White House at nine in the morning; but she presently appeared in a wrapper to implore him, with tears and promises of future good conduct, to get her out of trouble. She asked him to tell the President that it was ‘common to over-run appropriation, and that he would have to have the President’s approval before asking for the money.

“It can never have my approval,’ French wrote that Lincoln told him—’I’ll pay out of my own pocket first – it would stink in the nostrils of the American people to have it said that the President of the United States had approved a bill over-running an appropriation of $20,000 for flub dubs for this damned old house, when the soldiers cannot have blankets.’ He asked how [a decorator named] Carryl came to be employed. Major French declared he knew nothing about it, but thought perhaps Mr. Nicolay did. The President jerked the bellpull, and demanded Nicolay’s presence. ‘How did this man Carryl get into this house?’

‘I do not know, sir,’ said the discreet Nicolay.

‘Who employed him?’

‘Mrs. Lincoln, I suppose.’

‘Yes,’ French heard the President say—’Mrs. Lincoln—well, I suppose Mrs. Lincoln must bear the blame, let her bear it, I swear I won’t!’

Nicolay fetched Carryl’s bill, and Lincoln read, ”elegant, grand carpet, $2,500.’ I should like to know where a carpet worth $2,500 can be put,’ he said. Major French ventured that it was probably in the East Room. ‘No,’ said Lincoln ‘that cost $10,000, a monstrous extravagance.’ (The spelling is French’s.) It was all wrong to spend one cent at such a time, the President went on; ‘the house was furnished well enough, better than any one we ever lived in…’ He said that he had been overwhelmed with other business, and could not attend to everything. In his agitation, Lincoln arose and walked the floor, and he ended up by swearing again that he never would approve that bill.

In his interview with the President, French disclaimed all official connection with the bill, but he was not as uniformed as he implied. He well knew that his predecessor, W.S. Wood, had authorized the purchase of the wallpaper, and that it was chargeable to an annual appropriation of six thousand dollars, disbursed by the Commissioner of Public Buildings for repairs on the Executive Mansion. This money had been used for painting the outside of the house and other necessary work, and French did not want to be saddled with Wood’s mistakes. On taking office, he had told Carryl that there were no funds to meet his bill, and he had also vainly advised Mrs. Lincoln to put off papering the cost of the wallpaper tucked into an appropriation for sundry civil expenses. Presumably, this also covered the ‘elegant, grand carpet,’ as well as a charge of over twenty-five hundred dollars for new silver and replating of cutlery which Mrs. Lincoln had ordered without any authorization at all. 4

Although they started out as friends, Mrs. Lincoln came to view French as one of her White House adversaries, though he frequently was called on to help with her machinations of 1864. As with many presidential appointees, his relations with Mrs. Lincoln suffered with time. French wrote his brother that the “Republican Queen plagues me half to death with wants with which it is impossible to comply.” French wrote in 1864: “Mrs. Lincoln is boring me daily to obtain an appropriation to pay for fitting up a new house for her and the President at the Soldiers’ Home and I, in turn, am boring the Committee of Ways and Means. If Thaddeus [Stevens], the worthy old chairman, did not joke me off. I think I should get it….”5 Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, however, did not approve the expenditure to establish a year-round residence on the Soldiers’ Home grounds. When rumors of her alleged looting of White House possessions began after President Lincoln’s assassination, Mrs. Lincoln blamed French, saying, “There is no greater scamp, in this country than that man.”

According to historian Margaret Leech, “French was a stout, choleric old gentleman. With his arrogant mouth and his bristling gray side whiskers, brushed to the front, he resembled a cartoon of a Victorian papa. He kept a weather eye on Mrs. Lincoln, and winced suspiciously when she flattered him; but he was very patient with the Republican Queen.”6 In March 1863, Mrs. Lincoln wrote French: “Your kind note, accompanied by the sad & touching lines, were received by me on yesterday, allow me to express my thanks to you, for your remembrance. Such a mark of friendship, will be cherished, when in after years, we shall all have passed from the scene of the action. Our heavy bereavement, has caused this to be a very painful winter to me, yet situated as we are, being compelled to receive the world at large. I have endeavored to bear up, under our affliction, as well as I can.”7

French later wrote in his diary, two days after Mrs. Lincoln had finally left the White House on May 22, 1865: “It is is not proper that I should write down, even here, all I know! May God haver her in his keeping, and make her abetter woman.”8 By the beginning of 1866, French was comparing Mrs. Lincoln unfavorably with the daughters of President Andrew Johnson: “”Oh how different it is to the introductions to Mrs. Lincoln! She (Mrs. L.) Sought to put on the airs of an Empress – these ladies are plain, ladylike, republican ladies, their dresses rich but modest and unassuming…”9

French’s politicking threatened to undermine his hold on his office. According to the biographers of John Palmer Usher, French had been “appointed “disbursing agent for the work being done on the Capitol extension and dome, and in that potentially lucrative post French was able to maintain a staff of his own. When Usher replaced one of these clerks, challenged requests for funds before a House committee, and undercut French’s plans to build stables for the White House, the Commissioner protested to Lincoln that he was ‘cruelly treated by your Secretary of the Interior.’ Then he appealed to some of the many Senators whom he knew personally, asking them to introduce a bill to increase his authority.”10 In late March 1865, President Lincoln wrote French: “I understand a Bill is before Congress, by your instigation, for taking your office from the control of the Department of the Interior, and considerably enlarging the powers and patronage of your office. The proposed change may be right for aught I know; and it certainly is right for aught I know; and it certainly is right for Congress to do as it thinks proper in the case. What I wish to say is that if the change is made, I do not think I can allow you to retain the office; because that would be encouraging officers to be consistently intriguing, to the detriment of the public interest, in order to profit themselves.”11

Lincoln scholar Daniel Mark Epstein wrote: “The week before, after the fall of Richmond, Benjamin French had practiced lighting up the public buildings….French began with his own house, turning on all the gaslights, lighting the lanterns outdoors, and setting candles and astral oil lamps in each window. This as a signal for every householder in the neighborhood to do the same, and as if by contagion the whole city was soon ablaze with light.”12 French’s whole family was involved in preparing for Lincoln’s funeral. Anthony Pitch wrote: “Benjamin Brown French’s son, Ben, an engineer, had personally built the pine catafalque to hold the coffin. French’s wife, Mary, had sewn and trimmed the black cloth cover.”13

A few days after President Lincoln’s assassination, French claimed to have prevented an earlier assault on at the President’s Inauguration on March 4: “As the procession was passing through the Rotunda toward the Eastern portico a man jumped from the crowd into it behind the President. I saw him, & told Westfall, one of my Policemen, to order him out. He took him by the arm & stopped him, when he began to wrangle & show fight. I went up to him face to face, & told him he must go back. He said he had a right there, & looked very fierce & angry that we would not let him go one, & asserted his right so strenuously, that I thought he was a new member of the House whom I did not know & said to Westfall ‘let him go.’ While were thus engaged endeavouring to get this person back in the crowd, the president passed on, & I presume had reached the stand before we left the man. Neither of us thought any more of the matter until since the assassination, when a gentleman told Westfall that Booth was in the crowd that day, & broke into the line & he saw a police man hold of him keeping him back. W[estfall] then cam to me and asked me if I remembered the circumstance. I told him I did, & should know the man again were I to see him. A day or two afterward he brought me a photograph of Booth, and I recognized it at once as the face of the man with whom we had the trouble. He gave me such a fiendish state as I was pushing him back, that I took particular notice of him & fixed his face in my mind, and I think I cannot be mistaken. My theory is that he meant to rush up behind the President & assassinate him, & in the confusion escape into the crowd again& get away. But by stopping him as we did, the President got out of his reach. All this is mere surmise, but the man was in earnest, & had some errand, or he would not have so energetically sought to go forward….’”14

French had been in or near government ever since he arrived in Washington in 1833 to become assistant clerk of the House of Representatives. He later became clerk and commissioner of public buildings under President James Polk.

Footnotes

- Donald B. Cole and John J. McDonough, editors, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, 1828-1870, p. 375.

- Cole and McDonough, editors, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, p. 385.

- Cole and McDonough,editors, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, p. 382.

- Margaret Leech,Reveille in Washington, pp. 363-364.

- Leech, Reveille in Washington, pp. 294.

- Thomas F. Schwartz and Kim M. Bauer, Unpublished Mary Todd Lincoln, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Summer 1996, p. 5 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Benjamin Brown French, March 10, 1863)

- Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 308.

- Cole and McDonough, editors, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, p. 479.

- Cole and McDonough, editors, Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee’s Journal, p. 497.

- Elmo R. Richardson and Alan W. Farley, John Palmer Usher, Lincoln’s Secretary of the Interior, p. 35.

- CWAL, Volume VII, P. 266 (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Benjamin Brown French, March 25, 1865)

- Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammen/pin@field(NUMBER+pin2205))

- Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”, p. 229Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”, p. 229

Visit

Blue Room

Mary Todd Lincoln

Ward Hill Lamon

William S. Wood

John Watt

Redecorating the White House

John G. Nicolay

Thaddeus Stevens

Packing Up and Leaving

Mrs. Lincoln’s Shopping (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

President Lincoln’s Funeral

The Funeral Train of Abraham Lincoln