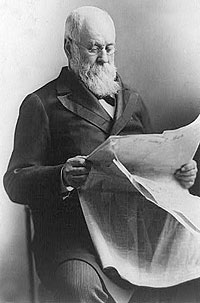

Managing editor and foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune from 1847-1862, Charles A. Dana resigned in a dispute with Editor Horace Greeley. Dana served as eyes and ears of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Lincoln in observing Grant’s command of army, starting in 1862. About his job, Dana wrote a friend: “I am here as a ‘special commissioner’ of the War Department, a sort of official spectator and companion to the movements of this part of the campaign, charged particularly with overseeing and regulating the paymasters, and generally with making myself useful.”1 He was useful to Ulysses S. Grant in reflecting his strategic vision and the contempt in which President Lincoln’s friend, General John A. McClernand, was held by other generals.

Back in Washington, Dana’s lengthy dispatches to the President occupied both telegraph operators and Mr. Lincoln. “Dana’s reports by telegraph were generally full, and the cipher-operators during that period had occasion to consult the dictionary many times for the meaning words new and strange to our ears. It was an education for us, particularly when errors occurred in transmission and words like ‘truculent’ and ‘hibernating’ had to be dug out of telegraphic chaos,” wrote David Homer Bates. “While Dana’s long despatches, ruthlessly criticizing or commending our generals, were being deciphered, Lincoln waited eagerly for the completed translations which he would usually read aloud with running comments, harsh criticisms being softened in the reading.”2

Dana was named Assistant Secretary of War in 1864 and served until 1865. In that office, according to historian Harry J Maihafer, “the approachable Dana was the ‘man to see’ at the War Department, especially since he contrasted so sharply with the brusque, imperious Stanton.”3 He assumed a variety of responsibilities, including the reorganization of the cavalry. According to friend and biographer James Harrison Wilson: “Almost immediately after his accession to office he organized a Secret Service force which became most efficient in the detection of frauds and disloyal practices against the government…..[Dana] used it vigorously and impartially for the detection and punishment of rascally practices, on the part of delinquent purchasing quartermasters and contractors for fuel, forage, harness, tents, clothing, and horses.”4

In 1864 Dana was particularly useful to President Lincoln and members of Congress because he was one of the few Administration officials who had spent a long period of time with General Grant. According to Wilson: “Many senators and representatives sought out Dana, and plied him with questions about Grant’s habits, his character, and his fitness for command…Congressman [Elihu Washburne’s] earnestness and force gradually swept aside all opposition in the House, while Dana’s advocacy, although less vehement, was regarded not only as far better informed but much more disinterested.”5

Wilson wrote that President Lincoln “appears to have taken Dana into his inmost confidence…and to have consulted him fully about the amendment to the Constitution to legalize the abolition of slavery, about the admission of Nevada as a State, and generally about where to get necessary votes in Congress to carry through the various policies of his administration.”6 In his Recollections of the Civil War, Dana recalled how President Lincoln chose to deal with a difficult vote on admission of Nevada as a state in March 1864:

For a long time beforehand the question had been canvassed anxiously. At last, late one afternoon, the president came into my office, in the third story of the War Department. He used to come there sometimes rather than send for me, because he was fond of walking and liked to get away from the crowds in the White House. He came in and shut the door.

‘Dana,’ he said, ‘I am very anxious about this vote. It has got to be taken next week. The time is very short. It is going to be a great deal closer than I wish it was.’

“There are plenty of Democrats who will vote it,’ I replied. There is James E. English, of Connecticut; I think he is sure, isn’t he?’

‘Oh, yes; he is sure on the merits of the question.’

‘Then,’ said I, ‘there’s ‘Sunset’ Cox, of Ohio. How is he?’

‘He is sure and fearless. But there are some others that I am not clear about. There are three that you can deal with better than anybody else, perhaps, as you know them all. I wish you would send for them.’

He told me who they were; it isn’t necessary to repeat the names here. One man was from New Jersey and two from New York.

‘What will they be likely to want?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know,’ said the President; ‘I don’t know. It makes no difference, though, what they want. Here is the alternative: that we carry this vote, or be compelled to raise another million, and I don’t know how many more, men, and fight no one knows how long. It is a question of three votes or new armies.

‘Well, sir, said I, what shall I say to these gentlemen?’

‘I don’t know,’ said he; ‘but whatever promise you make to them I will perform.”

I sent for the men and saw them one by one. I found that they were afraid of their party. They said that some fellows in the party would be down on them. Two of them wanted internal revenue collector’s appointments. ‘You shall have it,’ I said. Another one wanted a very important appointment about the custom house of New York. I knew the man well whom he wanted to have appointed. He was a Republican, though the congressman was a Democrat. I had served with him in the Republican county committee of New York. The office was worth perhaps twenty thousand dollars a year. When the congressman stated the case, I asked him, ‘Do you want that?’

‘Yes,’ said he.

‘Well, I answered, ‘you shall have it.’

‘I understand, of course,’ said he, ‘that you are not saying this on your own authority?”

‘Oh, no,’ said I; “I am saying it on the authority of the President.”

“Well, these men voted that Nevada be allowed to form a State government, and thus they helped secure the vote which was required. The next October the President signed the proclamation admitting the State. In the February following Nevada was one of the States which ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, by which slavery was abolished by constitutional prohibition in all of the United States. I have always felt that this little piece of side politics was one of the most judicious, humane, and wise uses of executive authority that I have ever assisted in or witnessed.7

Dana was an unabashed admirer of the President, later writing that Mr. Lincoln was a great military strategist and “a born leader of men. He knew human nature; he knew what chord to strike, and was never afraid to strike when he believed that the time had arrived.”8

Dana had a great capacity for work. James Harrison Wilson, who briefly headed the Army’s Cavalry Bureau, noted: “I made it a rule to lay nothing over, but to take action upon every case as it arose. This I learned from Dana, who had by all odds the greatest capacity for work and was the best administrator I ever met in public office. With intense powers of concentration he disposed of one case after another exactly as a competent mason lays bricks. He hardly got one settled in place before he took another in hand. And thus is was all day long, week in and week out.”9 Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote: “Dana…broke down the game of many a thieving quartermaster and contractor whose tricks and delinquencies in buying and selling fuel, forage, harness, tents, clothing, and horses might otherwise have robbed the Government of many of the hard-earned millions that went into the five-twenty bonds sold by Jay Cooke in the name of God and country.”10

Later, Dana served shortly as an editor for the Chicago Republican and as longtime publisher and editor of the New York Sun. He was disappointed in his expectations to be appointed as Collector of the Port of New York by both President Andrew Johnson and President Grant. His political positions—especially his strong criticism of corruption in the administration of President Grant and allegations of Grant’s alcoholism—caused Republicans considerable pain. He became almost as unpredictable as his own mentor, Horace Greeley, whom he supported for President in 1872. Dana’s memories were collected in a book, Recollections of the Civil War, that he dictated to Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell. In 1868, he and James Harrison Wilson wrote a laudatory campaign biography of Grant.

Footnotes

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 212.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, pp. 204-205.

- Harry J. Maihafer, The General and the Journalists: Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Charles Dana, p. 188.

- Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 185.

- Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 311.

- Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, pp. 314-315.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, pp. 161-162.

- Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 165.

- James H. Wilson, Under the Old Flag, Volume I, p. 342.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume II, pp. 610-611.

Visit

The War Department

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Ulysses S. Grant

Edwin M. Stanton

John A. McClernand

Elihu Washburne

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

The Journalist s (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Journalists

Charles A. Dana (Mr. Lincoln and New York)