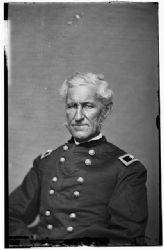

Adjutant-General of the Army who was assigned a major role in the recruitment of black soldiers for the Union Army in March 1863. He had previously served as chief of staff to General Winfield Scott.

One reason that Thomas was selected to lead black recruitment was that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton had little use for him. “Certainly Lorenzo Thomas and Edwin Stanton were extremely unlike in habit, temperament, and training. Thomas seems to have been infatuated with paper work and regulations,” wrote historian Dudley Taylor Cornish.1 Shortly after he took over at the War Department, Stanton proposed that Thomas act as an aide and bodyguard for the Commander-in-Chief. President Lincoln responded: “On reflection I think it will not do as a rule for the Adjutant General to attend me wherever I go; not that I have any objection to his presence, but that it would be an uncompensating encumbrance both to him and me. When it shall occur to me to go anywhere, I wish to be free to go at once, and not to have to notify the Adjutant General, and wait till he can get ready. It is better too, for the public service, that he shall give his time to the business of his office, and not to personal attendance on me. While I thank you for the kindness of the suggestion, my view of the matter is as I have stated.”2

Sending Thomas to the Mississippi River Valley seemed a convenient way to get rid of him. Cornish wrote: “With only twenty-four hours’ warning, Thomas was dispatched to the Mississippi with sweeping authority and huge responsibilities. Stanton probably found in the policy problem presented by the Negro soldier a solution to his personal problem. With the one stone of his orders of March 25 he killed the two birds: the organization of Negro troops was initiated by a high officer of the War Department and the secretary of war was freed of the presence of that officer in Washington.”3

John Hay recalled an interchange between President Lincoln and General Thomas on August 1, 1863, as Thomas was preparing to leave for the Mississippi River valley to begin his work. “General! You are going about a most important work. There is a draft down there which can be enforced.” Thomas replied: “I will enforce it.” Thomas later repeated the President’s remark at lunch, leading Hay to observe: “I regard his attitude as most significant. He is a man accustomed through a long lifetime to watch with eager interest the intentions of power and the course of events; till he has acquired an instinct of expediency which answers to him the place of sagacity & principle. He is a straw which shows whither the wind is blowing. The tendency of the country is to universal freedom, when men like Thomas make abolition speeches at public dinners.”4

A few days later, President Lincoln wrote General Ulysses S. Grant: “Gen. Thomas has gone again to the Mississippi Valley, with the view of raising colored troops. I have no reason to doubt that you are doing what you reasonably can upon the same subject. I believe it is a resource which if vigourously applied now, will soon close the contest– It works doubly, weakening the enemy & strengthening us, We were not fully ripe for it, until the river was opened. Now, I think at least a hundred thousand can, and ought to be rapidly organized along it’s shores, relieving all white troops to serve elsewhere.”5

Later in the month, Grant replied: “There has been great difficulty in getting able bodied negroes to fill up the colored regiments in consequence of the rebel cavalry run[n]ing off all that class to Georgia and Texas. This is especially the case for a distance of fifteen or twenty miles on each side of the river. I am now however sending two expeditions into Louisiana, one from Natchez to Harrisonburg and one from Goodrich’s Landing to Monroe, that I expect will bring back a large number. I have ordered recruiting officers to accompany these expeditions. I am also moving a Brigade of Cavalry from Tennessee to Vicksburg which will enable me to move troops to a greater distance into the interior and will facilitate materially the recruiting service.”

Grant added: “Gen. Thomas is now with me and you may rely on it I will give him all the aid in my power. I would do this whether the arming the negro seemed to me a wise policy or not, because it is an order that I am bound to obey and do not feel that in my position I have a right to question any policy of the Government. In this particular instance there is no objection however to my expressing an honest conviction. That is, by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weaken him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.”6

General Thomas and the President corresponded frequently on military and civil affairs while Thomas was in the field. On June 13, 1864, for example, Mr. Lincoln asked Thomas to investigate allegations that military recruiters in Kentucky were illegally recruiting slaves into the Army.

Thomas faced one more battle with the Secretary of War, however. In 1868 President Andrew Johnson ordered Thomas to replace Stanton in the Cabinet – after Ulysses S. Grant turned down the post. Stanton refused to let Thomas into his office, but the resulting controversy contributed to Johnson’s impeachment.

Footnotes

- Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Black Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865, p. 114.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.(Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Edwin M. Stanton, January 22, 1862).

- Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Black Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865, p. 114.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diaries of John Hay, p. 69 (August 1, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.(Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Ulysses S. Grant, August 9, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.(Letter from Ulysses S. Grant to Abraham Lincoln, August 23, 1863).

Visit