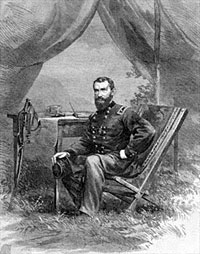

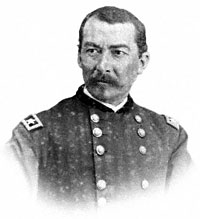

Union Army General Philip “Little Phil” Sheridan was an Army lieutenant at the outbreak of War. He rose through the ranks, first as a quartermaster and later as a cavalry officer and division commander in the West. He stormed Missionary Ridge at the Battle of Chattanooga in 1863. A dramatic, inspiring and irascible leader, he commanded Union Army in Shenandoah Valley in 1864 and devastated it. He was nearly defeated at Cedar Creek but rallied his troops for victory.

Presidential aide William O. Stoddard was in the office of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton when word of Confederate General Jubal Early’s defeat at Berryville Pike was received. Stanton was jubilant, wrote a note to Mr. Lincoln: “Take that to the President!” Stoddard ran back to the White House, up the stairs and into President Lincoln’s office, followed by several other aides. Mr. Lincoln calmly took Stanton’s note, read it, and announced: “Boys, that’ll do. I feel as Stanton does. We’ll shut up shop for the rest of today.” Stoddard, John Hay, and John G. Nicolay went out to celebrate – leaving Mr. Lincoln with Stanton, General Henry W. Halleck and some other generals.1 The President wired Sheridan: Have just heard of your great victory. God bless you all, officers and men. Strongly inclined to come up and see you.”2

In 1865, Sheridan joined Grant at Petersburg to deliver the blows that led to the defeat of Confederate forces at Appomattox. He had the confidence of General Ulysses S. Grant but often clashed with fellow generals like George Meade.

Sheridan’s first meeting with the President left Mr. Lincoln unimpressed. He thought the short cavalry commander to be a “brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.”3 Recalling his meeting on April 4, 1865 with President Lincoln, Sheridan wrote: “I proceeded with General Halleck to the White House to pay my respects to the President. Mr. Lincoln received me very cordially, offering both his bands, and saying that he hoped I would fulfill the expectations of General Grant in the new command I was about to undertake, adding that thus far the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac had not done all it might have done, and wound up our short conversation by quoting that stale interrogation so prevalent during the early years of the war, ‘Who ever saw a dead cavalryman?’ His manner did not impress me, however, that in asking the question he had meant anything beyond a jest, and I parted from the President convinced that he did not believe all the query implied.” Mr. Lincoln’s opinion of the hard-driving commander improved with time and he later told Sheridan: “General Sheridan, when this particular war began, I thought a cavalryman should be at least six feet four inches high, but I have changed my mind. Five feet four will do in a pinch.”4

When he received another promotion to head the Army of the Shenandoah in August 1864, President Lincoln told Sheridan that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton “had objected to my assignment to General Hunter’s command because he thought me too young, and that he himself had concurred with the Secretary; but now, since General Grant had plowed round the difficulties of the situation by picking me out to command the boys in the field, he felt satisfied with what had been done and hoped for the best.”5

Sheridan’s appointment was not General Grant’s first choice for the Shenandoah command. General George Meade had requested a transfer from the Army of the Potomac and Grant suggested that Grant be appointed to head the campaign in the Shenandoah. “The president refused, telling Grant that he had been resisting efforts to have Meade removed from the army’s command for months,” wrote historian Jeffrey D. Wert. “If he agreed to Meade’s reassignment, it would appear that he had given in to political pressure.” Instead, a few days later, Grant proposed Sheridan and Lincoln approved.5

After the Battle of Winchester, which Sheridan turned from a Union rout into a confederate rout, Lincoln told serenaders that it was “fortunate…for the Secesh that Sheridan was a very little man. If he had been a large man, there is no knowing what he would have done with them.”6

Sheridan was subsequently a military governor in Texas and Louisiana where he pushed for enrollment of black voters and sided with Radical Republicans. He became commander in chief of Army in 1884 and served until his death in 1888. He was active in the preservation of and creation of Yellowstone National Park as well as brutal treatment of western Indians.

Footnotes

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, pp. 207-208.

- Roy M. Basler, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (CWAL}, Volume VII, p. 13.

- Philip Sheridan, Civil War Memoirs, p. vii.

- Sheridan, Civil War Memoirs, p. 140.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, The Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 403.

- Jeffrey D. Wert, “Toiling in the Shadows: “The Grant-Made Command Relationship,” Civil War Times, June 2007, p. 49.

- CWAL, Volume VII, p. 57.

Visit

Ulysses S. Grant

Edwin M. Stanton

William O. Stoddard

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward