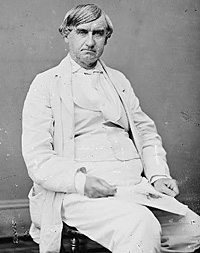

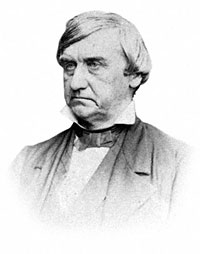

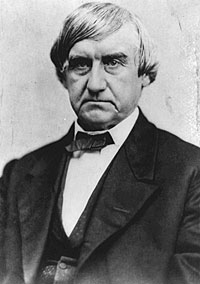

Judge Advocate General (1862-1865), Joseph Holt, was offered the post of Attorney General by President Lincoln in late 1864. A Kentucky Democrat turned Radical Republican, he had served briefly as Secretary of War under President Buchanan. He declined the second Cabinet offer on November 30, 1864- which went instead to James Speed. His name had also been one of many under consideration at a possible vice presidential nominee earlier in 1864 and was suggested as a possible successor for Secretary of the Interior Caleb Smith at the end of 1862.

With the end of the Buchanan administration, Holt returned to Kentucky and cooperated with Lincoln friend Joshua Speed cooperated to keep Kentucky in the Union. Historian Elizabeth D. Leonard wrote, “Determined to hold his beloved Kentucky in the Union (single-handedly if necessary), in the months following his departure from the War Department, Joseph Holt, now an independent citizen volunteering on the nation’s behalf, launched a personal campaign to ensure his home state’s loyalty.”1

Holt’s efforts were genuinely appreciated by the President, whose close Kentucky friend Speed wrote Holt in December 1861 that President Lincoln wanted to appoint him to a post “in some form commensurate with the service you have rendered the country.” Speed himself promoted Holt for secretary of War, arguing “You could render great service to the nation in that position.” Holt biographer Elizabeth D. Leonard wrote: “For his part, however, Holt seems to have been quite content with Lincoln’s decision, and indeed, it may have been he who recommended Stanton for the War Department slot in the first place, as Stanton had recommended him for the post back in late December 1860.”2

Holt returned to Washington as judge advocate general — in which position he advised President Lincoln regularly on military pardons. The position he accepted had changed dramatically under legislation passed in July 1862. Historian Elizabeth D. Leonard wrote: “On some occasions the trio considered more than seventy cases in a single sitting; at least once, they spent six straight hours in consultation.” Leonard wrote: “For each case that he brought to Lincoln’s attention, Holt summarized the charges, the evidence, the sentence, the opinion presented by previous reviewers, and his own recommendations. When Holt and the president disagreed on how to handle a particular case, it was typically Holt who took the harder line, though his often extended written opinions also reveal him to be capable of demonstrating ‘compassionate good sense.”3

The president frequently looked for mitigating circumstances that might justify commuting the sentence. Holt remembered: “I used to try and argue the necessity of confirming and executing these sentences. I said to him, if you punish desertion and misbehavior by death, these men will feel that they are placed between two dangers and of the two they will choose the least. They will say to themselves, there is the battle in front where they may be killed, it is true, but from which they also have a good chance to escape alive; while they will know that if they fly to the rear their cowardice will be punished by certain death.”4

In 1864, the Republican Party was searching for a War Democrat to nominate for Vice President as part of their “Union” ticket. “During the early hours of the [1864] convention Lincoln’s friend Leonard Swett came out for Holt,” wrote biographer Benjamin P. Thomas. John Nicolay, “on hand as an observer, wrote to Hay at the instance of Chairman Burton C. Cook of the Illinois delegation: ‘Cook wants to know confidentially whether Swett is all right; whether in urging Holt for Vice-President he reflects the President’s wishes; whether the President has any preference, either personal or on the score of policy; or whether he wishes not even to interfere by a confidential intimation.’ Lincoln endorsed on the letter: ‘Swett is unquestionably all right. Mr. Holt is a good man, but I had not heard or thought of him for V.P. Wish not to interfere about V.P. Can not interfere about platform. Convention must judge for itself.'”5 Andrew Johnson, the war governor of Tennessee, was nominated instead.

Holt was instrumental in publicizing a report in October 1864 that detailed the supposedly treasonous activities of the Sons of Liberty. The report was politically advantageous to Republicans, especially in Indiana. Holt wrote that “there has arisen together in our land an entire brood of…traitors…all struggling with the same relentless malignity for the dismemberment of our Union.”6

After Mr. Lincoln was assassinated, Holt prepared an order for the signature of President Andrew Johnson, which ordered the arrest of Jefferson Davis and five other suspected Confederate conspirators.

Holt’s public image was besmirched by his prosecution of the trials of persons accused of assassinating President Lincoln and a controversy over whether he had shown the military tribunal’s plea for clemency to President Andrew Johnson; Johnson denied it. Holt wrote Vindication to uphold his contentions. Holt’s sensitivity to criticism and tendency to believe in conspiracies contributed to his difficulties.

Holt had been a lawyer in both Mississippi and Kentucky.

Footnotes

- Elizabeth D. Leonard, Lincoln’s Avengers: Justice, Revenge, and Reunion After the Civil War, p. 23.

- Elizabeth D. Leonard, Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky, p.155.

- Leonard, Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky, p.159.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, p. 69 (Joseph Holt, October 29, 1875).

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 428.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry Of Freedom: The Civil War Era, p. 782.

Visit

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Leonard Swett

Abraham Lincoln and Kentucky

Pardons & Clemency