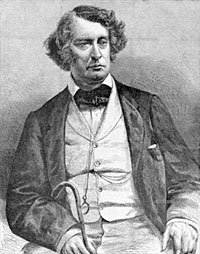

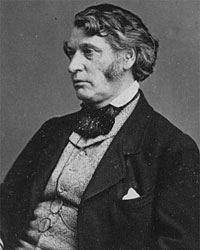

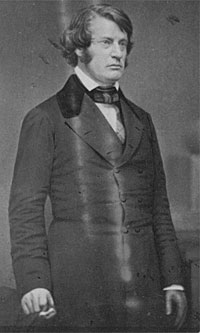

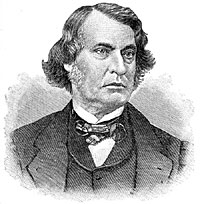

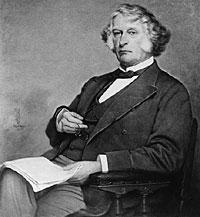

Senator from Massachusetts (1851-74, Free Soil, Republican), Charles Sumner served as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and was a supporter of President Lincoln’s war policies, but pushed him to end slavery. His vigorous support for suffrage and congressional control of Reconstruction caused friction with President Lincoln. In December 1861, President Lincoln told him: “Well, Mr. Sumner, the only difference between you and me on this subject of emancipation is a difference of a month or six weeks in time.”1 When Mr. Lincoln first arrived in Washington, Sumner declined Mr. Lincoln’s challenge to stand back to back to determine who was taller. President Lincoln recalled that Sumner “made a fine speech about this being the time for uniting our fronts against the enemy and not our backs. But I guess he was afraid to measure, though he is a good piece of man.”2

Sumner used his considerable contacts in England to soften the diplomatic impact of U.S. policy, especially during the Trent Affair in late 1861. In a letter to liberal British politician John Bright, Sumner wrote: “The President himself will apply his own mind carefully to every word of the answer, so that it will be essentially his; & he hopes for peace.”3 A few days later he wrote another British leader, Richard Cobden: “On reaching Washington for the opening of Congress, I learned from the Presdt. & from Mr Seward, that neither had committed himself on the Trent affair, & that it was absolutely an authorized act. Seward told me that he was reserving himself in order to see what view England would take. It would have been better to act on the case at once & to make the surrender in conformity with our best precedents; but next to that was the course pursued. Nothing was said in the message,—nor in conversation Lord Lyons was not seen from the day of the first news until he called with his Letter from Ld Russell. The question was not touched in the cabinet. It was also kept out of the Senate, that there might be no constraint upon the absolute freedom that was desired in meeting it. I may add, that I had cultivated with regard to myself the same caution.”4

Sumner was one of the first to learn of President Lincoln’s message to Congress about compensated emancipation. He was notified on March 6, 1862, according to biographer David Donald: ” Early that morning, even before he was dressed, he received an urgent summons to the White House. ‘I want to read you my message,’ Lincoln told him when he reached his office. ‘I want to know how you like it. I am going to send it in today.’ First the President read the manuscript aloud; then Sumner went over it himself. He had some reservations about some of the language—especially the word ‘abolishment’—but concluded that Lincoln’s style was ‘so clearly…aboriginal, autochthonous’ that it would not bear verbal emendation. Delighted with the content of the message, which pledged the cooperation and the financial assistance of the federal government to any state that began gradual, compensated emancipation, Sumner could hardly bear to part with the manuscript, which he went over again and again until Lincoln was obliged to say: ‘There, now, you’ve read it enough, run away. I must send it in to-day,’ and then gave it to his secretary for copying.”5

Sumner was a friend of Mary Todd Lincoln, and she would have liked to see him as Secretary of State in place of William H. Seward Sumner sponsored legislation to get her a needed widow’s pension that allowed her to return from her self-imposed exile in Europe. During the Lincoln Administration, Sumner was a frequent visitor at the White House where Mary Todd Lincoln was always appreciative of his attentions: “And I was pleased, knowing he visited no other lady. His time was so immersed in his business. And that cold & haughty looking man to the world would insist upon my telling him all the news & we would have such frequent & delightful conversations & often late in the evening—My darling husband would join us & they would laugh together, like two school boys.”6

Historian Stephen B. Oates noted that “Sumner was Mary’s favorite caller; she delighted in him, found his brilliance and fastidious ways irresistible. And he was always elegantly dressed, his favorite attire, consisting of a brown tailored coat, maroon vest, lavender or checked trousers, and a gold cane. Mary was flattered that this distinguished bachelor should care for her, that he could visit her in her drawing room and discuss diplomacy and read her letter from powerful Englishmen, that he could escort her regularly to the opera or the theater when Lincoln was too busy to go. Sumner made her feel like a cultivated woman, and she adored him and sent flowers for his table.”7 Mrs. Lincoln later told William Herndon: “Mr. Sumner & Mr. Lincoln were great chums [afer] they became acquainted with one and other: [they] watched Each other closely.”8 On one occasion Mr. Lincoln wrote Sumner for his wife: “Mrs. L. is embarrassed a little. She would be pleased to have your company again this evening at the Opera, but she fears she may be taxing you. I have undertaken to clear up the little difficulty. If, for any reason, it will tax you, decline without any hesitation, but if it will not, consider yourself already invited and drop me a note.”9

In March 1865, Mrs. Lincoln wrote Sumner from the White House: “The President & myself are about leaving for ‘City Point’ and I cannot but devoutly hope, that change of air & rest may have a beneficial effect on my good Husband’s health. On our return, about Wednesday, we trust you will be inclined to accompany us to the Italian Opera, ‘Ernani,’ is set aside for that evening.”10 In 1866, Mrs. Lincoln wrote : “Sumner, wrote me this week quite a confidential letter, announces he is soon to be married. I am much gratified, that his bachelor life, is coming to a close. I have no finer friend than him, or one, I like any better.”11

Sumner in turn said the Lincoln White House was the first “in which I ever felt disposed to visit the house and I consider it a privilege.”12 The President in return respected the proper Sumner, once saying “I have never had much to do with bishops where I live, but do you know, Sumner is my idea of a bishop.”13 So, although he and Sumner disagreed on Reconstruction policy, Mr. Lincoln kept open the lines of communication. Guard William Crook maintained that Sumner was actually one of the very few people Mr. Lincoln disliked. He recalled:

Mr. Sumner was a friend of the Chases, a particularly warm friend of Mrs. Kate Chase Sprague, who sympathized with him in his matrimonial difficulties. He was also a friend of Mrs. Lincoln. Not only was he present at state receptions and dinners (which, of course, would argue nothing), but he was Mrs. Lincoln’s escort at the second inaugural ball—especially invited, he told a friend, by Mr. Lincoln; and he was a member, with Senator and Mrs. Harlan…of the gay party which Mrs. Lincoln brought down to City Point after the fall of Richmond. The President did not interfere with Mrs. Lincoln’s social relations. This is only one instance of Mr. Lincoln’s largeness of mind, which did not allow personal matters to influence his judgment.

This was particularly noteworthy in the case of Sumner because, added to the fact that the Senator antagonized him in public matters, was the personal dislike of which I spoke. If what Elphonso Dunn told me was true, this was great enough to cause Mr. Lincoln to give instructions, on one occasion, that Senator Sumner should not be admitted to the White House. Dunn was on duty in the corridor, and the matter naturally made a great impression on him.14

Sumner also was a proponent of “State Suicide” theory of secession and his attitude toward reconstruction brought him into conflict with President Lincoln. But Carl Schurz argued that Mr. Lincoln manipulated Sumner to his advantage:

“Charles Sumner had formed a theory of State suicide which gave to the National Government absolute liberty of action as to the status of the States in rebellion and their reconstruction after the return of peace. This theory stood in sharp contrast to Lincoln’s ideas, but Sumner clung to it with his peculiar tenacity. The difference of opinion between the two men was so radical and outspoken that at the time of Lincoln’s second inauguration, an actual rupture of their personal relations was currently reported and widely believed. but in spite of their disagreements and jarrings, Lincoln at heart esteemed Sumner very highly, and Sumner, although sometimes seriously disturbed by Lincoln’s acts or failure to act, had implicit confidence in the rectitude of his character and the justness of his ultimate aims. Now, when Lincoln heard of the rumor of his personal rupture with Sumner, he at once resolved to discredit it by an open demonstration. On the evening of the inauguration ball he suddenly appeared in his carriage with Mrs. Lincoln and Mr. Colfax, Speaker of the House of Representatives, at Mr. Sumner’s house, and invited the Senator to join them. Being asked by the President, the Senator could not refuse. And then, arrived at the ball-room, the President further asked the Senator to offer Mrs. Lincoln his arm and to take her in. The Senator, with grave gallantry, complied, and appeared before all the assembled multitude, if not as a member of Lincoln’s family, at least as one of his dearest and most honored friends. After this their difference of opinion continued, although much softened; but there was no more talk of a personal rupture between Lincoln and Sumner. 15

In another book, Schurz wrote that President “Lincoln regarded and esteemed Sumner as the outspoken conscience of the advanced anti-slavery sentiment, the confidence and hearty cooperation of which was to him of the highest moment in the common struggle. While it required all his fortitude to bear Sumner’s intractable insistence, Lincoln did not at all deprecate Sumner’s agitation for all immediate emancipation policy, even though it did reflect upon the course of the administration. On the contrary, he rather welcomed everything that would prepare the public mind for the approaching development.”16

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died on October 12, 1864. Shortly thereafter, Senator Charles Sumner wrote President Lincoln: “Providence has given us a victory, in the death of Chief Justice Taney. It is a victory for Liberty & for the Constitution.”

Thus far the Constitution has been interpreted for Slavery. Thank God! it may now be interpreted surely for Liberty. The importance of this change cannot be exaggerated.

Still further, the power of the govt. in the conduct of the war, may now be vindicated, whether as regards the rebels or foreign nations.

To this end, the successor of Chief Justice Taney must be a person, who, besides the an acknowledged mastery of his profession, is an able, courageous, & determined friend of Freedom, who will never let Freedom suffer by concern or hesitation & he must also have an aptitude for public law.

At this moment, I think Mr Chase fulfills more of these requirements than any other person, & I write at once to express my hope that he may be nominated. Let it go forth that he is Chief Justice & our cause will gain every where.17

“No one understood the character of Charles Sumner better than the keen-witted President,” wrote Major Evan Rowland in Jones, Lincoln, Stanton and Grant. “And while he believed the senator to be a somewhat impractical statesman – while he believed that he was unnecessarily harsh in debate with those colleagues who happened to differ with him – he knew the senator from Massachusetts was patriotic, sincere, and true; faithful in his friendships, and unassailable by corruption.”18 Illinois politician Shelby M. Cullom observed: “Mr. Lincoln was the only man living who ever managed Charles Sumner or could use him for his purpose.”19

Offensiveness was an art form for Sumner, who was as honest as he was obnoxious but had more convictions than common sense. Strongly opinionated and a strong abolitionist, he was one of the founders of the Free Soil Party.

In May 1856 Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner spoke of South Carolina Senator Andrew P. Butler in words that led to Butler’s nephew, Preston Brooks, beating Sumner almost to death: “The senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight, with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight: I mean the harlot Slavery. For her his tongue is always profuse in words.”20 In retribution for the slight to Butler’s honor, Sumner was severely beaten on the Senate floor by South Carolina Democrat Congressman Preston S. Brooks on May 21, 1856.

Educated and erudite, Sumner valued his near martyrdom as much as his identity and honor. Later, Sumner was a leading opponent of President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction program and a strong proponent of Negro rights. He supported Greeley’s Democratic campaign for Presidency in 1872.

Footnotes

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, p. 5.

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences Illustrated, Volume II, p. 61.

- The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner, Volume II, p. 87.

- Sumner, Volume II, p. 93.

- David Donald, Charles Sumner, Vol. II, p. 51.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 319.

- Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 408.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editors, Lincoln’s Informants, p. 360.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 185 (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Charles Sumner, April 22, 1863).

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editors, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 209 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Charles Sumner, March 23, 1865).

- Thomas F. Schwartz and Kim M. Bauer, Unpublished Mary Todd Lincoln, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Summer 1996, p. 12 Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Alexander Williamson, September 29, 1866).

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 233.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 223.(Benjamin Perley Poore)

- Margarita Spalding Gerry, editor, Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, pp. 35-37.

- Carl Schurz, Autobiography of Carl Schurz, p. 310.

- Carl Schurz, Reminiscences of Carl Schurz p. 317.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from Charles Sumner to Abraham Lincoln, October 12, 1864).

- Major Evan Rowland, Jones, Lincoln, Stanton and Grant, p. 68.

- Shebly Moore Cullom, Fifty Years of Public Service, p. 152.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 124-125.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

William H. Seward

Red Room

The Conservatory

Carl Schurz

William Henry Crook

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Abraham Lincoln and Massachusetts

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Thirteenth Amendment

Henry Wilson

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)