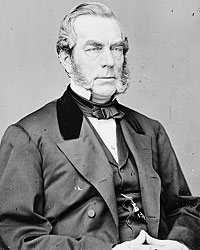

Governor of New York State (Republican, 1859-62), Edwin D. Morgan later served in Senate (1863-69), but his subsequent election bids were unsuccessful. From 1856-64 and 1872-1876, he was chairman of the Republican National Committee. He chaired the Republican’s national campaign committee in 1860, and in 1864, he chaired the Union Executive Committee which helped coordinate President Lincoln’s reelection campaign. Morgan supported President Lincoln’s war efforts and received a major general’s commission in the volunteer army in order to bolster his authority in New York State during the Civil War’s critical early months. He was a moderate on emancipation and declined renomination as governor in 1862 rather than fight what he anticipated might be a losing battle. His business background and wealth made him a key figure in Republican politics. In 1863 alone, Morgan paid $110,063 in federal income taxes — at a time when the salary of the President was just $25,000. He maintained mansions in New York, Washington and Newport, Rhode Island.

Journalist Noah Brooks described Morgan as having “a high narrow head covered with brown, stiff hair, and wears a somewhat forbidding and morose expression. He too has a brand new suit of clothes, is high shouldered and sedate, and is not especially notable in appearance save in the size of his nose, which is as big and romanesque as Seward’s.”1 Morgan biographer James A. Rawley wrote: “He brought very considerable abilities to the halls of the lawmakers and to the executive chamber. They were the qualities of the merchant prince: a lively eye to financial measures, unflagging physical endurance, a sense of duty to the public, celerity of decision, integrity, urbanity, tact, and Christian humanitarianism. One would find it hard to say whether he was a ‘conservative’ or liberal.’ As early as 1850 he sacrificed business to principle in espousing the Wilmot Proviso. As late as 1863 there was doubt about his approval of emancipation.”2

Morgan won election to the Senate in 1863, succeeding Republican Senator Preston King. During the July 1863 draft riots, he opposed imposition of martial law in New York City. Morgan remained a political power in state politics to be reckoned with by President Lincoln, who was anxious to repair rifts within the Republican Party as the 1864 campaign approached. Morgan was also a business power in New York City. In early June 1864, Morgan suggested several qualified replacements for Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Cisco. Two of them declined the post and three others were rejected by Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, who instead appointed Treasury official Maunsell B. Field. Historian James A. Rawley wrote:

Immediately Morgan interposed objections on the grounds of Field’s unfitness and the political unwisdom of the appointment. Chase stubbornly sent Field’s name to the president. Morgan carried his objections to Lincoln and submitted three acceptable names, R. M. Blatchford, Dudley S. Gregory, and Thomas Hillhouse, his former Adjutant General. ‘It is in my judgment discreet to appoint a Republican at New York at this time,’ he told the president.

Lincoln now made his own position clear to the secretary of the Treasury. ‘I can not without much embarrassment make this appointment, principally because of Senator Morgan’s very firm opposition to it…It will really oblige me if you will make choice among these three, or any other man that Senators Morgan and Harris will be satisfied with, and send me a nomination for him.’

Morgan expected to prevail. On June 30 he wrote Hillhouse, ‘I write this now to say that I hope you will be prepared to make any necessary sacrifice, that may be required of you in behalf of the Public interest. I have this morning heard that no appointment will be made for a short time in the place of Cisco but that he will hold on a while. I do not know how long, nor what will come of it. Quite privately, I will say to you that I never will consent to the appointment of Mr. M. B. Field as Cisco’s successor.”

Chase had determined to force the issue. He submitted his resignation, apparently believing that the president would refuse it, as he had once before, and make concessions. Instead Lincoln promptly answered, “Your resignation of the office of the secretary of the Treasury, sent me Yesterday, is accepted.”3

The resignation caused considerable consternation in the White House and elsewhere in Washington. Presidential John Hay recorded in his diary that night: “In the afternoon I talked over the matter with the President. He said Chase was perfectly unyielding in this whole matter of Field’s appointment: that Morgan objected so earnestly to Field that he could not appoint him without embarrassment & so told the secretary, requesting him to agree to the appointment of Gregory Blatchford or Hillhouse or some other good man that would not be obnoxious to the Senators: the Secretary still insisted, but added that possibly Mr Cisco would withdraw his resignation: the President answered that he could not appoint Mr Field but wd wait Mr Cisco’s action. Yesterday evening a letter came from the Secretary announcing first the intelligence that Mr. Cisco had withdrawn his resignation. This was most welcome news to the President. He thought the whole matter was happily disposed of. Without waiting to read further he put the letters in his pocket & went at his other work. Several hours later, wishing to write a congratulatory word to the Secretary, he took the papers from his pocket, and found his bitter disappointment the resignation of the Secretary. He made up his mind to accept it. It meant, “You have been acting very badly. Unless you say you are sorry, & ask me to stay & agree that I shall be absolute and that you shall have nothing, no matter how you beg for it, I will go.” The President thought one or the other must resign. Mr Chase elected to do so.4

President Lincoln needed the support of the conservative wing of New York Republicans which Morgan represented. Chase had rejected several suggestions which Morgan had made about possible replacements and some other potential candidates had declined the nomination. After a Cabinet meeting five weeks later, Welles wrote in his diary: “I was with the President on Wednesday when Governor Morgan was there, and the President produced the correspondence that had passed between himself and Chase at the time C. resigned. It was throughout characteristic. I do not think the even was wholly unexpected to either, and yet both were a little surprised. The President fully understands Chase and had made up his mind that he would not be again overridden in his own appointments. Chase, a good deal ambitious and somewhat presuming, felt he must enforce his determinations, which he had always successfully carried out. In coming to the conclusion that a separation must take place, the President was prompted by some, and sustained by all, his Cabinet without an exception. Chase’s retirement has offended nobody, and has gratified almost everybody.”5

Morgan turned down appointment as Secretary of the Treasury by President Lincoln on February 13, 1865. Thurlow Weed recalled the subject of Fessenden’s replacement was raised in a late February visit to the White House:

“In the winter of 1865 I received a note from President Lincoln asking me to come to Washington. Immediately after my arrival I called at the White House, and although early, several persons were waiting to see the President. Mr. Lincoln requested me to call at an hour indicated, when I found him alone. He commenced the conversation by saying: ‘You will remember that after the result of the late presidential election was known, I told you that I expected to have more influence with the President now that he had got a new lease. You and your friends thought that they were severely tried during my first four years. I did not say much about it then, but intended, if circumstances were favorable, to even up the account. I shall have Mr. Fessenden’s resignation of the Treasury Department on Monday. Now, if you had the vacancy to fill, whose name would you send to the Senate?

I replied that, although wholly unprepared for such a question, yet I was not unprepared with a name that I would suggest for his consideration. I then mentioned Governor Morgan as, in my judgment, a suitable man for the place, provided it would answer to give the two leading places in his cabinet to the State of New York.

“I anticipated this name,’ said Mr. Lincoln; ‘and even if I had not intended to consult your wishes I should have felt quite safe in trusting the matter to your judgment. I can afford to give Governor Morgan the Treasury, even though Mr. Seward has the State Department, because the Governor can be confirmed, and the people will sustain the appointment. But,’ he added, ‘this could not be done if a word or whisper of it gets out. Can you and I keep the secret? He then inquired if there was any doubt of Governor Morgan’s acceptance. I told him I thought not; that he had been a capable and successful merchant; that he had shown great executive and financial ability as governor of our State; and that I could not doubt of his acceptance of a department in which he could render much greater service to his country. And, after some further conversation, Mr. Lincoln allowed me to suggest – in the strictest confidence and in general terms – to Governor Morgan that a contingency might happen in which he would be called to the discharge of other duties.

On the way to the cars I stopped at Governor Morgan’s house, and, after very earnest injunctions of secrecy, made the suggestion in terms so vague and general as to leave the Governor wholly in the dark as the nature of the duties referred to, and as to my authority to make the suggestion.6

Weed agreed to secrecy but tried to grease the way by talking to Governor Reuben Fenton about a possible replacement for Morgan in the Senate. He quickly discovered that Fenton himself, although newly elected, was interested in the seat. But Fenton’s ambition was to be delayed, noted Weed:

“When the time came for Mr. Lincoln to supply the vacancy occasioned by the resignation of Mr. Fessenden, he took the Senate and the country by surprise in the nomination of Governor Morgan, who, so entirely had I failed to prepare him for the event, was quite as much surprised as his colleagues. Governor Morgan, as soon as he could leave his seat, went over the White House, and informed the President that he must decline the appointment. He consented, however, to leave the President time for consideration. I returned immediately to Washington, and after a long interview with Governor Morgan, was constrained to report his persistent declination to the President. I failed, however, as I then and now believe, to ascertain what Governor Morgan’s real reasons for refusing the Treasury Department. Upon reporting that failure to Mr. Lincoln, he said: ‘That is very awkward, but we must look elsewhere for a secretary. Who is your next man?” I replied that I was too much mortified by this miss-fire to try again. Mr. Lincoln said: “I am disappointed, for I thought Governor Morgan would be willing to help us ‘run the machine; ‘ but I had two other men in my mind. What do you say to Mr. McCulloch or Mr. Hooper?” I replied that I had a high appreciation of the character and services of both gentlemen, but that I was personally almost unknown to them…”7

“I was appointed to the position once during Mr. Lincoln’s administration, without being consulted at all,” recalled Morgan. “It was to succeed Senator [William P.] Fessenden, and no one was more surprised than myself to hear the appointment read when it was sent to the Senate for approval. I asked them to lay the matter over until I should return, and then drove to the White House and represented to Mr. Lincoln, that for many reasons, I could not accept the position, and the appointment was withdrawn.”8 According to biographer James A. Rawley:

Morgan was silent about his reasons for declining. But the press had a variety of explanations. As Secretary of the Treasury Morgan would be obliged to sever his extensive and lucrative business connections; and political considerations may also have played a part. The attempted appointment was said to be a scheme of Seward’s and Weed’s. Morgan might be a rival to Seward for the presidency in 1868. In the Treasury, however, not only would he be safely out of the way, but Seward could accept the vacant Senate seat and thus be in an independent place to jockey for the presidency.

A more plausible political explanation was that the vacant seat might fall to Governor Reuben Fenton, thus augmenting the Radical opposition to Lincoln and changing the complexion of politics in New York State, where the Union victory in November 1864 had been small.9

Senator Morgan played an important role in the 1864 Republican campaign — before and after the convention in Baltimore in June. Presidential aide John G. Nicolay wrote President Lincoln from New York on August 30: “Gov. Morgan and Senator Morrill have been through most of the New England States. They report an improved state of feeling in all respects, and say we will certainly [carry] Maine at the approaching September election, by a good majority.”10

During the 1860 presidential campaign and throughout the Lincoln presidency, Morgan was a frequent correspondent with Mr. Lincoln, offering advice on military affairs and political appointments. He also occasionally offered praise, as for the president’s “Corning letter” in June 1863: “I cannot refrain from expressing the gratification I have felt this morning, in reading your letter to the officers of the Albany Vallandingham Meeting. It is timely, wise, one of your best State Papers and was really necessary under the drift which affairs have taken.”11

Morgan’s business career had expanded from that of a Hartford, Connecticut grocer to a prosperous New York City banker, broker and merchant. He broke into politics a Whig — serving as a state senator 1850-1853 and chairman of the New York Whig Central Committee. He switched to the Republican Party in 1855. But in post-war New York, Morgan had a hard time competing with younger, rougher Republicans like Roscoe Conkling and Reuben Fenton. He failed to win another election.

Footnotes

- Noah Brooks, Mr. Lincoln’s Washington, p. 135 (March 13, 1863).

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, pp. 267-268.

- Rawley, ‘Lincoln and Governor Morgan,’ Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, March 1961, Vol. VI, No. 5, pp. 292-293.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, pp. 212-213.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 93-94 August 5, 1864.

- Rawley, “Lincoln and Governor Morgan,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, March 1951, Volume VI, No. 5, p. 296.

- Harriet A. Weed, editor, The Autobiography of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, pp. 620-621.

- Weed, editor, The Life of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, pp. 621-622.

- Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 202.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 155 (Letter from John G. Nicolay to Abraham Lincoln, August 30, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Abraham Lincoln, Monday, June 15, 1863).

Visit

Salmon P. Chase

John Hay

Thurlow Weed

Maunsell B. Field

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Edward D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

1864 Patronage Problems (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Finance