James H. Lane, known as “Bloody Jim” and “Grim Chieftain,” was a Senator from Kansas (Republican, 1861-66). He participated in the defense of Washington after the fall of Fort Sumter in 1861—coordinating protection of the White House with David Hunter and Cassius M. Clay. Presidential aide John Hay recalled in his diary on April 18 1861: “The White House is turned into barracks. Jim Lane marshaled his Kansas Warriors today at Willard’s and placed them at the disposal of Mj. Hunter, who turned them tonight into the East Room. It is a splendid company—worthy of such an armory. Besides the western Jayhawkers it comprises some of the best materiel of the East. Senator [Samuel C.] Pomeroy and old Anthony Bleecker stood shoulder to shoulder in the ranks. Jim Lane walked proudly up and down the ranks with a new sword that the Major had given him.”1

Eleven days, later, Hay made another diary entry: “Going into Nicolays room this morning, Carl Schurz and Jim Lane were sitting. Jim was at the window filling his soul with gall by steady telescopic contemplation of a Secession flag impudently flaunting over a roof in Alexandria. ‘Let me tell you’ said he to the eloquent Teuton, ‘We have got to ship these scoundrels like hell[,] Carl Schurz. They did a good thing stoning our men at Baltimore & shooting away the flag at Sumpter. It has set the great North a howling for blood and they’ll have it.”2 Lane later served at the Missouri front as a brigadier general until March 1862.

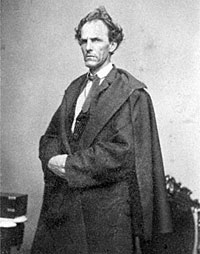

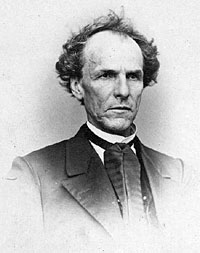

While eating dinner one late in late April, John Hay was a accosted by Lane: “A gaunt, tattered, uncombed and unshorn figure appeared at the door and marched solemnly up to the table. He wore a rough [rusty?] overcoat,a torn shirt and suspenderless breeches. His neck was innocent of collar, guileless of necktie. His thin hair stood fretful-porcupine-quill-wise upon his crown. He sat down and gloomily charged upon his dinner. A couple of young exquisites were eating and chatting opposite him. They were guessing when the road would be open through Baltimore. ‘Thursday’ growled the grim apparition, ‘or Baltimore will be laid in ashes.”3

Lane urged the President to allow recruitment of Indians to defend Kansas and he differed with the President on fugitive slaves. At a meeting on January 17, 1862, the President told Lane: “Yes. General, I understand you. And the only difference between you and me is that you are willing to surrender fugitives to loyal owners in case they are willing to return; while I do not believe the United States government has any right to give them up in any case. And if it had, the people would not permit us to exercise it.”4

Lane had drifted into antagonism to the President in 1863 and often feuded with his Senate colleague Pomeroy. However, Pomeroy supported Salmon Chase for the 1864 Republican nomination and Lane in turn supported Lincoln—at least in part to assure he would control Kansas patronage. In June 1864, he turned back radical opponents to the President in the Union League and nominated Lincoln the next day at the Baltimore “National Union” convention. The move effectively squelched any opposition to the President.

Lane had served Indiana in Congress (1853-55) and as Lieutenant Governor before moving to Kansas and participating in the territory’s war between pro- and anti-slavery forces. Historian Walter A. McDougall wrote that Lane had “decamped to Kansas in 1855, expecting that his record as a hero of the Mexican War and a Jacksonian congressman would catapult him to leadership of the Kansas Democrats. He sensed at once how the dispute over slavery was wrecking that party. Instead, he helped launch a Free-Soil party and ran men and guns into Kansas along ‘Lane’s trail’ through Iowa. His career hiccuped after he killed a rival land speculator and Stephen Douglas disowned him.”5 Historian George Fort Milton wrote: “General Lane was poorly educated, coarse and uncouth. His hair stood out in every direction, his mouth suggested plug tobacco and heavy curses and his dress was almost as extraordinary as his appearance. But this was not all of the man. Positive, insistent, domineering and dominant, he commanded his fellows. His energy was amazing and his calfskin vest was likely to appear in any part of the wilderness.”6 Robert Henry Browne wrote that to describe Lane, “as he should be described, can not be attempted. There were many bright and talented men who knew him well, yet no one of them has ever been able to reveal his true character in a short sketch. He was a man who was not all bad, nor was he by any means all good; but for the niche he filled in the border war he was built up and put together with as much harmony and appropriateness as a well-molded ship is for the sea. He had the brawny strength, the strong limbs, the swelling chest, the bronzed and wind-swept face, the toughened muscles and sinews, that no one in the work he was in and had in hand from day to day could get along without.”

He was keen-witted, crafty, and had the cunning of a fox. He could fight, and had no personal fear about it. He could often do better than make a direct assault, for he knew well how to annoy, harass, surprise, and disturb his enemy, and his fights were usually brought on in the least expected maneuver. He could run away to entice his enemy to disadvantage. In all, he could more effectively carry on the border war than any other man in the work on either side.7

An opportunist and demagogue, Lane was rude and crude. However, he could stir passions with his rhetoric and actions. He switched his allegiances from the Radical Republicans to President Andrew Johnson after the war and committed suicide in 1866.

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 9.(April 23, 1861).

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 13 (April 29 1861).

- Burlingame and Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 9 (April 23, 1861)

- Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, The Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 123.

- Walter A. McDougall, Throes of Democracy: The American Civil War Era, 1829-1877, p. 405.

- George Fort Milton, The Eve of Conflict, p. 195.

Visit

Salmon P. Chase

John Hay

David Hunter

Carl Schurz

Abraham Lincoln and Kansas

Abraham Lincoln and the Radical Republicans